The Roughest Riders (6 page)

Read The Roughest Riders Online

Authors: Jerome Tuccille

Roosevelt now had an opportunity to test his own mettle in combat as assistant to Colonel Leonard Wood, head of the First Volunteer Cavalry. Wood was a medical doctor, and it was during his tenure as personal physician to Presidents Grover Cleveland and William McKinley that he developed a friendship with Roosevelt. He had taken part in the last campaign against the Native American chieftain Geronimo in 1886, and in that same year he was awarded the Medal of Honor for carrying dispatches across a hundred miles of hostile territory and for leading an infantry unit in combat against the Apaches. Still, he had no experience as an officer in the field against a modern, well-armed enemy.

It wouldn't be long before Roosevelt would be joining the assemblage of volunteers as they stormed into the inferno of battle under Wood's command. The flamboyant crew of soldiers were known as “Teddy's Terrors” at first, and later “Roosevelt's Rough Riders.” Roosevelt himself was nothing if not good copy. The newspapers loved him for the color he provided, particularly in the form of audacious words that poured out of his mouth. Wood resented the attention given to his subordinate; but Wood's Terrors or Wood's Rough Riders didn't have the same alliterative ring as the other names, and

newspaper reporters knew a good headline when they saw one. Far be it from them to abandon a catchy title for the sake of accuracy.

Roosevelt had been in love with the cowboy lifestyle since his days on the American plains, and in forming his troop, he recruited a raunchy band of individualists, men who did not look at life with the spirit of decorum and conventionality that prevailed on the East Coast. Out of an estimated 25,000 enlisted men who volunteered, he selected 1,241 young soldiersâplus 54 officersâall of them expert marksmen and seasoned cavalrymen. In addition to the cowboys and the Western gunmen, Roosevelt also attracted a claque of Eastern bluebloods, bored and wealthy Ivy Leaguers cast more or less in his own mold who were looking for adventure and thought that a popular war against ethnic inferiorsâthe “Garlics,” some of them called the Spaniardsâwould be a jolly way to find it.

On his way to Cuba, however, Roosevelt would meet up with another type of soldier who was not cut from the common cloth. These were the black soldiers who had already proven themselves in war. They were the Buffalo Soldiers, and within months they would join Roosevelt and his Rough Riders on their charge up a remote hill in the torrid heat and humidity of the Cuban jungle.

T

heodore Roosevelt, freshly out from under the dubious supervision of Secretary of the Navy John D. Long, lost no time inciting the wrath of his new commanding officer, Colonel Leonard Wood. San Antonio, Texas, was hot in May, and after an intense day of drilling under the scorching sun, Roosevelt, getting overly friendly with his band of ragtag volunteers, announced, “The men can go in and drink all the beer they want, which I will pay for!” To the dismay of his superiors, he hopped in a van and led his troops to the nearest saloon, where they spent the evening drowning their thirst thanks to their leader's generosity.

Wood reprimanded Roosevelt for his flagrant breach of military discipline. It hardly instilled respect, Wood scolded, for officers to go out drinking with their men. Roosevelt absorbed the rebuke, saluted Wood, and promptly vanished into the night. A while later, he returned to Wood's tent and told the colonel, “Sir, I consider myself the damnedest ass within ten miles of this camp. Good night, sir.”

The soldiers in training remained in San Antonio for a few weeks, earning the respect and gratitude of the locals, who admired the men's spirit and appreciated their patronageâeven without

Roosevelt's companionship in the barrooms. When it was time to leave for war a month later, the townspeople treated them to a farewell party, complete with a band led by the son of German immigrants who composed a tune called “Cavalry Charge.” The piece culminated with drums, cymbals, and live cannon fire. With the sound of cannons roaring in the night, some of the men thought the town was under attack and began firing their own weapons randomly into the air. Men, women, and children dove under picnic tables or ran into the woods. The electricity failed, apparently the result of an overload on the grid, cloaking the town in darkness except for the flashes from guns and cannons.

“I was in the Franco-Prussian War and saw some hot times,” the German American composer said the next day, “but I was about as uneasy last night as I ever was in battle.”

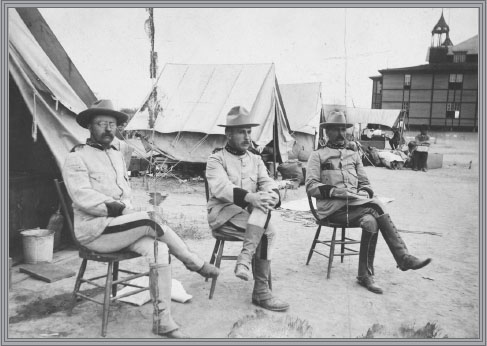

San Antonio, Texas, was blistering hot in May 1898, when Teddy Roosevelt arrived to assemble the Rough Riders under the command of Colonel Leonard Wood.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (LC-DIG-ppmsca-37599)

In contrast, Roosevelt and his Rough Riders found the whole incident highly amusing, a good preparation for the real battle ahead. They departed from San Antonio by train laughing, heading for Tampa, Florida, the final stop before embarking for Cuba. The only one who was not amused was Roosevelt's commander, Colonel Wood.

Preceding Roosevelt and his entourage to Tampa by two months was the all-black Twenty-Fifth Infantry, the first troops ordered into war by President McKinley. “The Negro is better able to withstand the Cuban climate than the white man,” reasoned the commanding general of the US Army, Nelson A. Miles. The Buffalo Soldiers had last seen action in the Johnson County War of 1892, from which they emerged as heroes. On their way southeast in March through the Great Plains region, the veteran Indian-fighters passed through a long string of towns in which they were greeted with waves and cheers by supportive locals. The black soldiers waved back, distinctive in their dark blue shirts, khaki breeches, and ten-gallon hats. American flags adorned their train as it pulled into St. Paul, Minnesota, where a gathering of white settlers clamored for tunic buttons to keep as souvenirs. The Buffalo Soldiers accommodated the townspeople by pulling buttons off their uniforms and tossing them into the crowd. “We had to pin our clothes on with sundry nails and sharpened bits of wood,” one of the soldiers commented afterward.

It was the first time the entire regiment had met together since 1870, and the journey was “a marked event, attracting the attention of the daily and illustrated press,” wrote Chaplain Theophilus G. Steward, the only black officer in the infantry unit. No sooner were they reunited, however, than they were ordered to separate.

At the Union Depot at St. Paul, two companies were told to proceed directly to Key West, and six other companies were directed to Chickamauga in Georgia. Those six, accompanied by the regimental band, were the first troops to arrive in the park at Chickamauga, where they joined with a large contingent of white troops.

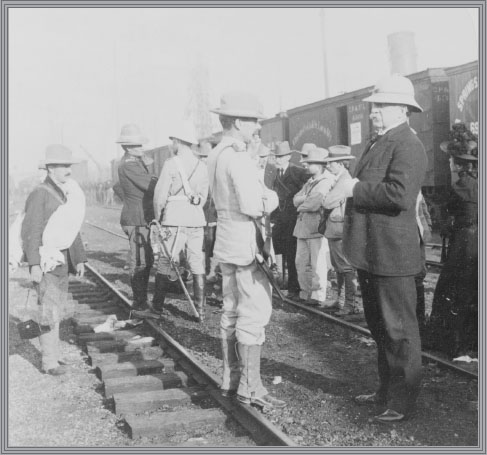

Commander of the US Army, Major-General Nelson A. Miles, believed that black soldiers were better equipped genetically to withstand the torrid weather of the tropics than their white counterparts.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (LC-USZ62-122405)

“The streets were jammed, the people wild with enthusiasm,” wrote scholar William G. Muller in his history of the event. And then the mood of jubilation turned to one of hostility and hatred.

The trainload of black infantrymen crossed an invisible but real divide, the Mason-Dixon Line; they had made the transition from the North to the South.

“It is needless to attempt a description of patriotism displayed by the liberty loving people of the country along our line of travel until reaching the South,” wrote Herschel V. Cashin, a white historian of the era who rode with the troops. In the South, he said, “cool receptions told the tale of race prejudice even though these brave men were rushing to the front in the very face of grim death to defend the flag and preserve the country's honor and dignity.”

As the Twenty-Fifth headed deeper into the South, the War Department activated four new regiments of black soldiers to join themâthe Seventh through the Tenth US Volunteer Infantries, led mostly by white officers. The Eighth had been stationed at Fort Thomas, Kentucky, where there had been three officers' messes: one for white captains and higher-ranking white officers, a second for black lieutenants, and a third for mostly white field and staff officers. Two black staff officersâthe chaplain and the assistant surgeonâdined with the lieutenants.

Even as the black infantrymen traveled through the hostile South on the way to war, some military voices came forward with concern. Writing to the editor of the

Cleveland Gazette

, Chaplain George Washington Proileau of the Ninth Cavalry wrote, “Talk about fighting and freeing poor Cuba and of Spain's brutalityâ¦. Is America any better than Spain? Has she not subjects in her very midst who are murdered daily without a trial of judge or jury? Has she not subjects in her borders whose children are half-fed and half-clothed, because their father's skin is black?” The chaplain, himself a former slave, continued, “Yet the Negro is loyal to his country's flag. O! He is a noble creature, loyal and trueâ¦. Forgetting that he is ostracized, his race considered as dumb as driven cattle, yet, as loyal and true men, he answers the call to arms and with blinding

tears in his eyes and sobs he goes forth: he sings âMy Country 'Tis of Thee, Sweet Land of Liberty,' and though the word âliberty' chokes him, he swallowed it and finished the stanza âof Thee I sing.'”

Yet, the majority of African American civilians endorsed the war, some on the grounds that it was the patriotic thing to do, and others with the opinion that it would bring their people in contact with other “colored” cultures. “Will Cuba be a Negro republic?” asked an article in the

Afro-American Sentinel

, out of Omaha, Nebraska. “Decidedly so, because the greater portion of the insurgents are Negroes and they are politically ambitious. In Cuba the colored man may engage in business and make a great success. Puerto Rico is another field for Negro colonization and they should not fail to grasp this great opportunity.”

It also helped that no army regiments had a better reputation than the colored regiments, and, claimed Steward, none performed better in combat. He hoped that black soldiers, or American soldiers of any color, would never have to fight another war, but he said that if black troops were called on to serve their country again, he had no doubt they would do their unenviable duty as patriotic Americans.

So, while some African Americans believed that black troops should take no part in a war of white imperialism, a larger part thought it was worth the effort to secure a foothold in a predominantly black culture where there were greater opportunities for advancement. As for the soldiers themselves, many of them reasoned, logically enough, that their patriotism during this new war would finally earn them the respect they deserved. So they soldiered on, at first thinking they were headed into a warzone on a tropical island south of Florida, but soon realizing they were already traveling through enemy territory within US borders.

The Twenty-Fifth Infantry was the first to arrive in Chickamauga Park, Georgia, where it was soon joined by the other black

contingents. One of the volunteers with the Eighth was eighteen-year-old Benjamin O. Davis, who would go on to become the first African American general in the US Army four decades later, on October 25, 1940. Their instructions changed from day to day; some heard they would eventually be departing for Tampa, Florida, others that they were headed for the Dry Tortugas, a remote outpost situated due west of the Florida Keys and north of Havana, Cuba. Other units had orders to go to New Orleans, Louisiana. Their final destination was never in question, however; they would all eventually be risking their necks in the hellhole of wartime Cuba.