The Roughest Riders (9 page)

Read The Roughest Riders Online

Authors: Jerome Tuccille

The days passed with the men overwhelmed by acute boredom. There was little to do but fall in line for inspections, pull guard duty, exercise as best they could in the limited space, and gamble away the little money they had.

Finally, word came that it was time to raise anchor and set off toward Cuba. They left Port Tampa the morning of June 14 to great fanfare, with bands playing, flags flying, and the men clustered like ants on the rigging as the flotilla slowly steamed out to sea.

The transports presented a picturesque spectacle as they departed toward the open ocean. The ships sailed out in three columns, each column separated from the others by a thousand yards, with the

ships about four hundred yards apart from one another. Smaller vessels escorted the American fleet from Port Tampa until it reached a point between the Dry Tortugas and Key West, where it was met by the battleship

Indiana

and thirteen other war vessels. When they passed around Key West, the

New York

was in the lead, followed by the

Iowa

and the

Indiana.

The official count was fifty-three ships in all, including thirty-five transports, four auxiliary vessels, and fourteen warships. The American armada presented an impressive sight for a fledgling empire about to expand its global reach.

“The passage to Santiago was generally smooth and uneventful,” noted General Shafter in his official report. Colonel Wood described the passage from his own perspective with a bit more color: “Painted ships in a painted oceanâimagine three great long lines of steaming transports with a warship at the head of each line ⦠on a sea of indigo blue as smooth as a millpond. The trade wind sweeping through the ship has made the voyage very comfortable.”

It was not so comfortable for the men in the hold, however. Body lice had infested them and their clothing for weeks before they left, and without the ability to boil their uniforms and underwear aboard ship, they had to seize every opportunity to tie their belongings to ropes on deck and drag them in the water behind the moving ships to dislodge the parasites.

The weather was balmy until the fleet entered the Windward Passage between the western coast of Haiti and the eastern tip of Cuba, where high winds and rough seas buffeted the ships. Throughout the journey, the Americans avoided an encounter with Cervera and his Spanish armada, which had slipped past Sampson's North American Squadron on its voyage to Havana. After rounding the east coast of Cuba on the morning of June 20, the US ships headed west past Guantanamo Bay along the southern coastline toward the town of Daiquiri, about eighteen miles east of Santiago de Cuba.

Despite the cool breeze, a heavy mist obscured the shore as the men prepared to disembark once the order came. At about five o'clock the next morning, the heavy gray clouds began to evaporate, the wind picked up, and breaking daylight revealed the great flotilla of transports stretching as far as five miles out to sea, with the warships closer in. Towering rocky hills devoid of foliage dominated the coastline. The boats anchored about noon slightly west of the harbor, where Rear Admiral Sampson was anxiously waiting. He boarded General Shafter's vessel, the

Seguranca

, and together they debarked to confer with Cuban General Calixto GarcÃa, who occupied the area with about four thousand well-armed, battle-hardened troops. That afternoon they met with the sixty-year-old Cuban leader in the town of Aserradero in Santiago Province.

The US fleet followed a route southward along the west coast of Florida, then southeast across the Bahama Channel, and finally around the Windward Passage on its way to Daiquiri, near Santiago de Cuba on the island's southern shore.

Based on a map that appeared in

San Juan Hill 1898

by Angus Konstam, Osprey Publishing, 1998.

GarcÃa had been anticipating their arrival ever since he received a letter from Major-General Nelson A. Miles dated June 2, 1898, which read in part: “It would be a very great assistance if you could have as large a force as possible in the vicinity of the harbor of Santiago de Cuba, and communicate any information[,] by signals which Colonel Hernandez will explain to you[,] either to our navy or to our army on its arrival, which we hope will be before many days.”

Miles had also requested that GarcÃa march his rebels to the coast and harass the Spanish troops in and around Santiago de Cuba. He advised the Cubans to attack the Spanish at all points and

prevent them from sending reinforcements to the region. He also asked him to try to seize any commanding positions to the east or west of Santiago de Cuba before the Americans arrived. Once there, American ships would begin to bombard the entire coastal area with the big guns on the battleships.

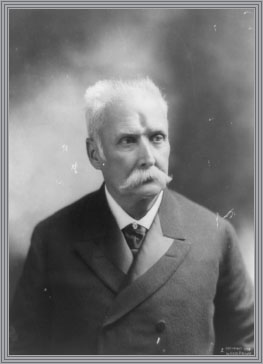

Calixto GarcÃa, the elderly leader of the Cuban rebels in the region around Santiago de Cuba, coordinated his efforts with the American invasion forces, which were in the process of disembarking after their voyage from Florida.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division (LC-USZ62-91767)

GarcÃa took some umbrage at Miles's deprecating tone. Hadn't they, GarcÃa and his rebels, already been shedding their own blood to free their land from Spanish rule for decades before the Americans entered the fray? Nevertheless, he needed American support to win the war, and he responded cordially, saying that he would “take measures at once to carry out your recommendationsâ¦. Will march without delay.”

GarcÃa performed his job well, attacking Spanish positions in and around the landing zone as the rebels burst out of the bush and fired volley after volley at the enemy. Although they could not see what was happening up in the hills, the Americans could hear from their ships the rebel shouts echoing in the air:

“¡Viva Cuba Libra! ¡Viva los Americanos!”

Shafter, Sampson, and GarcÃa devised a battle plan to attack the rear of the Spanish garrison in the vicinity, following the debarkation of the American troops on June 22. But the process of unloading thousands of soldiers, animals, and equipment onto shore proved to be a logistical nightmare. The fleet now lay anchored a mile and more offshore, and the men had to file onto small boats and make the crossing to land in heavy seas. The Spanish soldiers occupied the higher peaks and could use the men and boats for target practice as they struggled to navigate the choppy water. GarcÃa's forces held the terrain on both sides of the Spanish garrison but were unable to move in for the kill without American help. To soften Spanish resistance, Sampson ordered a steady bombardment of the villages along the coast as Miles had promised, an effort that continued for two to three hours. The boom of the big guns on

the

New Orleans

,

Detroit

,

Castine

,

Wasp

,

Suwanee

, and

Texas

echoed off the cliff walls, and shells exploded spectacularly in the jungle growth on the higher elevations.

“The first day[,] Sampson got all his gunboats together and fired shots all around the landing, tearing everything around there all to pieces,” wrote C. D. Kirby, with the black Ninth, to his mother. “The following day we all landed and went about a mile before we struck camp.”

The American shells exploded on Spanish forts, blockhouses, and various entrenchments in Daiquiri, Siboney, and other villages strewn for twenty miles along the coast, clearing the way for the Americans to come ashore. But the process of getting them there continued to be hazardous.

“We did the landing as we had done everything elseâthat is, in a scramble, each commander shifting for himself,” Roosevelt wrote. They landed at the squalid port village of Daiquiri, where a railroad and ironworks factory was located. There were no landing facilities there, so the American transport ships were forced to remain offshore near the gunboats, while the men jumped down onto the few landing vessels they had and then rowed toward land in a heaving sea.

The larger boats carried ten or twelve men each, while the smaller craft had room for only six or seven. Making matters worse, the uniforms issued to the men were made of heavy canvas and wool, more suitable for winter in Montana than for summer in Cuba. The thickness of the Rough Riders' campaign hats alone could stop anything short of an axe, one of the men quipped. The clothing, along with their weapons, shelter-halves, and other equipment, weighed the men down unmercifully in the damp air and mounting heat. Slowly, the men inched toward shore and approached an abandoned and dilapidated railroad pier. To get from the boats onto land, the men had to leap from the water amid turbulent waves while in full

possession of their gear. The pack mules and horses had to be pushed off the boats so they could swim ashore on their own.

Not everyone made it safely to land. A boat transporting black soldiers from the Tenth capsized, and two of the soldiers attempted to leap onto the dock but fell beneath the churning waters of the harbor and sank under the weight of their blanket rolls and other equipment. One of the Rough Riders, Captain William Owen “Buckey” O'Neill, a former mayor of Prescott, Arizona, plunged into the water in full uniform in an attempt to save them. His efforts, sadly, failed, and the men vanished from sight and lost their lives before they had a chance to fire a single shot at the enemy.

T

he troops of the black Twenty-Fifth were among the first to land a short distance from the pier. “We landed in rowboats, amid, and after the cessation of the bombardment of the little hamlet and coast by the men-of-war and battle-ships,” wrote a soldier in the unit. “We then helped ourselves to cocoanuts [

sic

] which we found in abundance near the landing.”

The first wave of troops had now landed on Cuban soil, and the veteran soldiers pitched right in and looked about for suitable campsites. Most of them, both black and white, had seen action in earlier wars, with battle scars to show for their combat experience, but some were young recruits no more than seventeen or eighteen years old and weren't yet familiar with the rigors of warfare. Some of the Rough Riders had also made it onto dry ground, if one could describe the wet Cuban coastline that way. These volunteers, although experienced adventurers and hunters from the West or thrill-seeking wealthy Easterners, were, like the teenage soldiers, as yet untested against live enemy fire.

The troops were wet and tired, and some of the animals were even worse off. Sadly, one of Roosevelt's mounts, Rain in the Face,

swam the wrong way and drowned among the heaving waves. The other, Texas, made it to the beach with most of the other animals. Texas showed signs of wear and tear after having spent two weeks on the transport ship, and he was breathing heavily after his efforts to swim ashore, but Roosevelt was delighted that his horse perked up in short order and was able to carry his master.

About one-third of the men and equipment reached land by nightfall on June 22, but it would take another two days for the entire army to hit the beach. While the men were struggling toward land, a group of horsemen came galloping down from the hills waving a Cuban flag above their heads. They also carried a white flag, a prearranged signal that indicated the Spanish forces under General Arsenio Linares had abandoned Daiquiri and taken up defensive positions in the hills outside Santiago.

The troops pitched camp below the cliffs rising from the beach. They bivouacked on the beach outside Daiquiri where a railroad crossed a wagon road leading to the coastal town of Siboney, about six miles to the west. The Tenth, a black unit under the command of General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheelerâas were the Rough Ridersâhad also made it ashore earlier than most of the other troops. Already in his sixties, Wheeler had been a Confederate army general during the Civil War, and many of the men thought he had lost his grip on reality by this time. He seemed to have his wars mixed up when he exhorted his troops in Cuba to charge because “we've got the damn Yankees on the run again.” A small, intense man and a graduate of West Point, he represented Alabama in Congress for seven terms after the Civil War and was second in command to Shafter in Cuba. Wheeler was the physical opposite of Shafter, who weighed in at well over three hundred pounds and was, at that moment, indisposed with an attack of gout aboard the

Seguranca.