The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (17 page)

Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

The contact with the hot ears of corn had felt very agreeable, and I changed places to find another hotter pile. I dreamt of glory, and I should have liked to put on my king’s crown. But I would have had to go up to my room and fetch it, and it was so comfortable here on the corn! I took my crystal carafe stopper out of my pocket, and looked through the prismatic facets at my picture, then at the cherries, then at the ears of corn scattered on the floor. The ears of corn especially produced an extremely langorous effect seen in this manner, set off by all the colors of the spectrum. An infinite laziness came over me, and with slow movements I took off my pants. I wanted my flesh to touch the burning corn directly. I slowly poured a sack of grain over myself. The grains trickled over my body, soon forming a pyramid that entirely covered my belly and my thighs.

I was under the impression that Señor Pitchot had just started off on his morning inspection tour and would as usual not be back before the lunch hour. I therefore had plenty of time to put back all the spilled corn in the sack. This thought encouraged me and I poured out still another sack of corn in order to feel the weight of the pyramid of grain progressively increase on top of me. But I had erred in my calculations as to the duration of Señor Pitchot’s walk, for the latter suddenly reappeared on the threshold. This time I thought I would die of shame at seeing myself caught in my voluptuous attitude. I saw consternation contract his features and, backing away without saying a word, he disappeared, this time for good. I did not see him again before lunch time.

At least an hour must have gone by meanwhile, for the sun had long since left the spot where I remained without moving from the moment of Señor Pitchot’s unexpected reappearance. I was stiff and ached all over from having kept the same half-lying position for so long. I began to pick up all the corn I had spilled, putting it back in the sack. This operation took a long time, for I was only using my two hands. Because of the unusual size of the sacks I did not seem to be making any headway; I was several times tempted to leave my work unfinished, but immediately a violent sense of guilt seized me in the center of my solar plexus, and then I would begin again with fresh courage to put the grains of corn back into the sack. As I neared the end my work became more painful because of the constant temptation to leave everything as it was. I would say to myself, “It’s good enough as it is,” but an insuperable force pressed me to keep right on. The last ten handfuls were a real torture, and the last grain seemed almost too heavy to lift from the ground. Once my task was finished to the end I felt my spirit suddenly calmed, but the

weariness that had come over my body was even greater. When I was called to lunch I thought I would never be able to climb the stairs.

An ominous silence greeted me as I entered the dining room, and I immediately realized that I had just been the subject of a long conversation. Señor Pitchot said to me in a grave tone,

“I have decided to speak to your father, so that he will get you a drawing teacher.” As though I felt outraged by this idea, I indignantly answered,

“No! I don’t want any drawing teacher, because I’m an ‘impressionist’ painter!”

I did not know very well the meaning of the word “impressionist” but my answer struck me as having an unassailable logic. Señora Pitchot, dumfounded, broke into a great peal of laughter.

“Well, will you look at that child, coolly announcing that he’s an ‘impressionist’ painter!”

And with this she went off into an immense, fat and generous laugh. I became timid again, and continued to suck the marrow of the second joint of a chicken, noticing that the marrow had exactly the color of Venetian red. Señor Pitchot launched into a conversation on the necessity of picking the linden blossoms toward the end of the week. This linden blossom picking was to have consequences of considerable moment for me.

But before I enter into the absorbing, cruel and romantic story which is to follow, let me first continue, as I had promised, to describe the rigorous apportioning of the precious time of my days lived in that unforgettable Muli de la Torre. This is necessary, moreover, to situate precisely, against a chronological, ordered and clear setting, the vertiginous love scenes which I am about to unfold to you. Here, then, is the neurotic program of my intense spring days.

I excuse myself for repeating once more in summary the manner in which these began, so that the reader may more readily connect this part with the rest of my program and be in a position to obtain the necessary view of the whole.

Ten o’clock in the morning—awakening, “varied exhibitionism,” esthetic breakfast before Ramon Pitchot’s impressionistic paintings, hot coffee-and-milk poured down my chest before leaving for the studio. Eleven to half past twelve—pictorial inventions, reinvention of impressionism, reaffirmation and rebirth of my esthetic megalomania.

At lunch I collected all my budding and redoubtable “social possibilities,” in order to understand everything that was going on at the Mill through the conversations sprinkled with euphemisms of Señor and Señora Pitchot and Julia. This information was precious in that it revealed to me plans of future events by which I could regulate the delights of my solitude while establishing an opportunistic compromise between these and the marvels of seduction offered me by the whole series of activities connected with the agricultural developments of the place. These events always brought with them not only the flowering of new myths but also the apparitions (in their natural setting) of their protagonists who were heretofore unknown to me—the linden blossom picking (in this connection only women were mentioned), the wheat threshing, performed by rough men who came from far away, the honey gathering, etc.

III. Thirty Years Before—Thirty Years After

As a little boy at school, I stole an old slipper belonging to the teacher, and used it as a hat in the games I played in solitude.

In 1936, I constructed a Surrealist object with an old slipper of Gala’s and a glass of warm milk.

Years after my school-boy prank, a photo of Gala crowned by the cupolas of Saint Basil revived my early fantasy of the “slipper-hat.”

Finally Madame Schiaparelli launched the famous slipper-hat. Gala wore it first; and Mrs. Reginald Fellowes appeared in it during the summer, at Venice.

IV. The Orifice Enigma

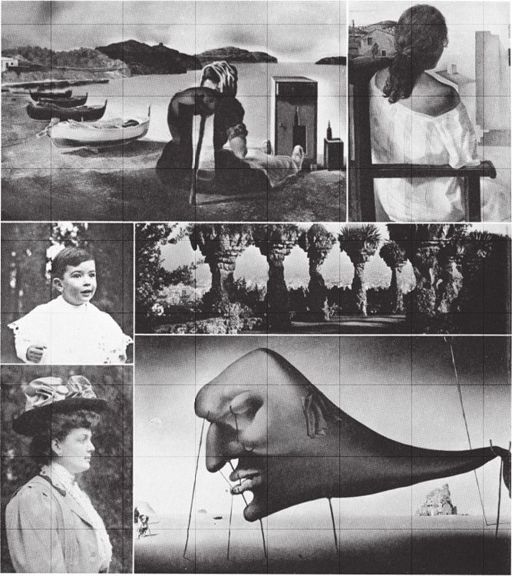

“Weaning of Alimentary Furniture”: my nurse, from whose back a night table has been extracted.

“Portrait of My Sister.” During the execution of this picture, I had an instantaneous vision of a terrifying rectangular hole in the middle of her back.

Photo of Dali at the time he visited the Park Guell in Barcelona.

Avenue in the Park Guell. The open spaces between the artificial trees gave me a sensation of unforgettable anguish.

Ursulita Matas, who took me to visit the Park Guell.

“Sleep,” 1939 painting in which I express with maximum intensity the anguish induced by empty space.

Hérisson.

The afternoon was dedicated almost exclusively to my animals which I kept in a large chicken coop, the wire mesh of which was so fine that I could even confine lizards there. The animals in my collection included two hedgehogs, one very large and one very small, several varieties of spiders, two hoopoes, a turtle, a small mouse caught in the wheat bin of the Mill where it had fallen, unable to get out. This mouse was shut up inside a tin biscuit box on which there happened to be a picture of a whole row of little mice, each one eating a biscuit. For the spiders I had made a complicated structure out of cardboard shoe boxes so as to give each kind of spider a separate compartment, which facilitated the course of my long meditative experiments. I managed to collect some twenty varieties of this insect, and my observations on them were sensational.

Araignée.

The monster of my zoological garden was a lizard with two tails, one very long and normal and the other shorter. This phenomenon was connected in my mind with the myth of bifurcation, which appeared to me even more enigmatic when it manifested itself in a soft and living being–for the bifurcated form had obsessed me long before this. Each time chance placed me in the presence of a fine sample of bifurcation, generally offered by the trunk or the branches of a tree, my spirit remained in suspense, as if paralyzed by a succession of ideas difficult to link together, that never succeeded in crystallizing in any kind of even poetically provisional form. What was the meaning of that problem of the bifurcated line, and especially of the bifurcated object? There was something extremely practical in this problem, which I could not take hold of yet, something which I felt would be useful for life and at the same time for death, something to push with and to lean on: a weapon and a protection, an embrace and a caress, containing and at the same time contained by the thing contained! Who knows, who knows! Wrapped in thought, I would caress it with my finger in the middle where the two tails of the lizard bifurcated, went off in two different directions, leaving between them that void which alone the madness peculiar to my imagination would perhaps some day be able to fill. I looked at my hand with its fingers spread out, and their four bifurcations disappeared in the imaginative and infinite prolongation of my fingers which, reaching toward death, would never be able to meet again. But who knows? And the resurrection of the flesh?