The Silk Road: A New History (27 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

Although the Arab commander had promised Devashtich safe conduct, he reneged on his word. Al-Tabari describes his grisly end. The commander “slew al-Diwashini [Devashtich], crucifying him on a [Zoroastrian] burial building [naus]. He imposed upon the people of Rabinjan the obligation to pay one hundred [dinars] if the body were removed from its place.... He sent al-Diwashini’s head to Iraq and his left hand to Sulayman b. Abi al-Sari in Tukharistan.”

90

The method of killing suggests that Devashtich was an important figure. Because

Devashtich represented Sogdian resistance, the Arab commander chose an extreme method to dispose of his body.

91

(He was subsequently dismissed for having used such a gruesome punishment.)

Devashtich’s death was just one chapter, and a minor one at that, in the Islamic conquest of Samarkand. Within a few decades Muslim troops had secured the region, and over time Persian displaced Sogdian and Islam replaced Zoroastrianism. At the 751 battle of Talas, which took place at what is now Kazakhstan, Muslim troops defeated a Chinese army largely because the forces of a nomadic people, the Qarluqs, defected to the Islamic side. Four years later General An Lushan rose up against the Tang dynasty, and the dynasty was forced to withdraw its troops from Central Asia to suppress the mutiny. These two events in rapid succession meant that, after the mid-eighth century, the city of Samarkand and the surrounding region of Sogdiana no longer looked east to China. The Islamicization of Sogdiana prompted many of the Sogdians living in China to settle there.

The Mount Mugh documents predate both the Islamicization of Central Asia and the spread of paper-making technology to the region. The different materials used to write the Mount Mugh documents show that local rulers were willing to pay for Chinese paper because of its durability and convenience, but the residents of Central Asia continued to use leather for important documents, like the single letter in Arabic that Kratchkovsky deciphered, and reserved willow sticks for less important matters like household accounts.

A rare indicator of long-distance trade at Mount Mugh is the Chinese paper found there. Three Chinese-language documents were pieced together from eight fragments, all on recycled paper originating in China. No one at Mount Mugh actually wrote Chinese. One of the documents originated as an official document written in Wuwei, Gansu, a thriving city on the Chinese silk route to the east of Dunhuang. After it was discarded and sold as paper (the reverse side was blank and could still be used), Silk Road traders brought it west some 2,000 miles (3,600 kilometers) to Mount Mugh.

92

In the eighth and ninth centuries, Chinese paper reached far into Central Asia, as far as the Caucasus Mountains, to the site of Moshchevaia Balka, literally “ravine of the mummies/relics.” The site, consisting of burials either on limestone terraces or dug out of the hillside, near the northeast edge of the Black Sea is the farthest location from China where Chinese paper has been found to date. In the early twentieth century, excavators unearthed a few scraps of paper with Chinese writing on it. The most complete document, 6 inches (15 cm) by 3 inches (8 cm), contained a few lines in running hand that give the date and then the amount of various expenditures (2,000 coins, 800 coins). Although extremely fragmentary, it appears to be a ledger of expenses.

93

The site produced other items, all clearly of Chinese origin: a piece of silk with a design showing a Buddhist deity on it as well as a man riding a horse (the prince Siddhartha before he left the palace?), a scrap of paper with a Buddhist text, and a fragment of an envelope from some paper mache object. These items clearly demonstrate that at least Chinese paper and silk paintings—and possibly even Chinese merchants—had reached the Caucasus region sometime between the eighth and ninth centuries.

94

During the eighth century people living in Central Asia learned how to manufacture paper. An Arab account reports that at the 751 Battle of Talas the Abba-sid Caliphate won a resounding victory over the Chinese and brought back prisoners of war to their capital at Baghdad. Some of the POWs taught their captors how to make paper.

95

As with other legends about technological transfer, this one is not necessarily credible.

96

The techniques of making paper—beating a mixture of organic material and rags to a pulp and drying it on a screen—were not difficult to replicate. The technology steadily spread out from central China, reaching Central Asia by the eighth century. After the year 800, paper gradually replaced leather as the primary writing material of the Islamic world. Paper had many advantages over leather: low in cost and quickly produced, it was far more convenient than leather and much more available than papyrus, which grew only in Egypt. Paper entered Christian Europe through its Islamic portals at Spain and Sicily, in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries.

There is no question that the Chinese invention of paper—unlike silk—transformed the societies it touched. Silk, however great its allure in the pre-modern world, was used primarily for clothing or for decorative purposes. If not available, other textiles could easily replace it, and in Central Asia cotton often did. Paper, by contrast, marked a genuine breakthrough. With the introduction of cheap paper, books went from being luxury items to a commodity that many could afford, and educational levels rose accordingly. Unlike parchment or leather, paper absorbed ink, so it could be used for printing. The world’s major printing revolutions—whether with woodblocks in China or moveable type in Europe—could not have occurred without paper.

The different scholars who have worked on the Sogdian Ancient Letters, the Panjikent excavations, the Afrasiab murals, and the Mount Mugh letters concur that they contain surprisingly few depictions of trade. The Ancient Letters, though written by merchants, document mostly small-scale purchases. Similarly, excavations at Panjikent have produced few trade items, and the city’s wall paintings hardly ever show merchants and never actual commerce. The same is true of the Afrasiab murals. A French archeologist with extensive experience digging at Samarkand, Frantz Grenet has summed up the situation trenchantly: “In the whole of Sogdian art there is not a single caravan, not a single ship, except in the pleasure boats of the Chinese empress” at Afrasiab.

97

Many paintings have been found on the walls in the over 130 houses excavated so far at Panjikent, yet they do not show business dealings. Similarly, the Mount Mugh documents all involve locally made goods, except for silk and paper. And the technologies for making those two items were moving west out of China into Central Asia at just this point.

The evidence at hand makes it clear that Silk Road commerce was largely a local trade, conducted over small distances by peddlers. Technologies, like those to make silk and paper, and religions, like Zoroastrianism and later Islam, moved with migrants, who brought the technologies and religious beliefs of their motherland with them to their new homes, wherever they settled.

DOCUMENTS TURN UP IN UNUSUAL PLACES

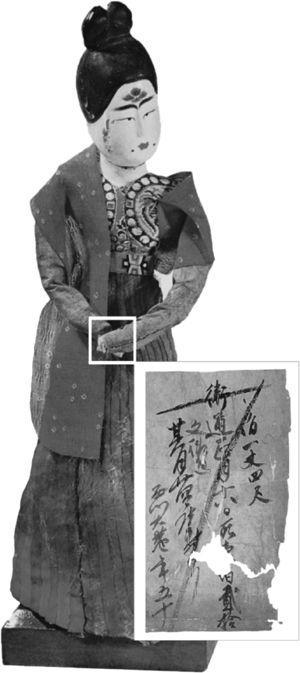

If you look closely, you can see paper sticking out from the wrists of this tomb figurine, which was excavated in Turfan and dates to the 600s. Her arms are made from rolled-up recycled paper, which was then twisted into shape. Figurines like this have been steamed apart, revealing various types of documents, including pawn tickets, one of which, with a big black cancelation mark in the shape of a 7, is shown here. The pawn tickets mention place names in Chang’an, a crucial clue to identifying the place of manufacture. Courtesy of Xinjiang Museum.

CHAPTER 5

The Cosmopolitan Terminus of the Silk Road

Historic Chang’an, Modern-day Xi’an

T

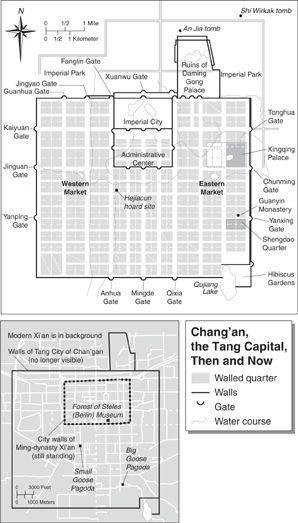

he modern city of Xi’an offers more archeological attractions than any other Chinese destination. The famous terra-cotta warriors are only an hour’s drive away, and the Silk Road has left many traces in the city. Many non-Chinese minority peoples inhabit the city, which was similarly diverse during the Tang dynasty when the city was called Chang’an. The elegant figurine on the facing page, who wears an outfit combining Chinese and Sogdian elements, was made in Chang’an. Chang’an was so big that only in the past ten years has modern Xi’an expanded beyond its Tang-dynasty boundaries. With a population of over ten million, it is certainly the largest city in the northwest.

As the city’s residents often remind visitors when composing toasts, the city served as the capital of ten dynasties. Seven of these dynasties were short-lived and controlled only the immediate region. Three major dynasties that governed a unified China designated Chang’an as their capital: the Former Han (206

BCE

–9

CE

), the Sui (589–617), and the Tang (618–907). While a political center, the city also served as a point of departure for those who, like Xuanzang, traveled west on the Silk Road. Before setting off, Xuanzang visited the city’s Western Market, home to many Sogdians, because the city’s residents could provide him with better advice than anyone else in China.

This inland city was also a starting-off place for those traveling by sea from China to points west. These ocean voyagers proceeded overland (the Yellow River was not navigable) to different ports on the Yangzi River or directly to China’s coast. At these ports, they caught boats sailing along the world’s most frequented sea route in use before 1500: that linking the Chinese coastal ports with Southeast Asia, India, the Arabian world, and the east African coast.

1

The city received visitors traveling overland and by sea throughout the first millennium, the peak centuries of Silk Road traffic. After the fall of the Han dynasty in 220 and before the reunification of China by the Sui dynasty in 589, different dynasties led by nomadic peoples ruled the various regions of China, which was never united during that long period. In the north, the Northern Wei (386–534) was the longest-lived dynasty, and two brief dynasties, the Northern Qi (550–77) and Northern Zhou (557–81), succeeded it.

Modern Xi’an contains many traces of the past. Chinese law requires that the archeological authorities be notified each time that a bulldozer unearths something ancient, a frequent event in a city like Xi’an, where each year archeologists uncover several hundred tombs from both the Han and Tang dynasties.

2

During the Northern Zhou, a graveyard for high-ranking officials was located in the northern suburbs of modern Xi’an. Some of the newest evidence about overland migration comes from the recent discovery of several tombs of Sogdians who moved to Chang’an and other northern Chinese cities in the late sixth and early seventh centuries.

Two Sogdian tombs in particular have excited much attention since their discovery: that of An Jia (d. 579), unearthed in 2001, and of Shi Wirkak, discovered in 2004. In the fall of 2005 Xi’an archeologists also excavated the tomb of the first Indian buried in the city. His epitaph identified him as a Brahman, meaning someone from India, not necessarily of high caste, with the Chinese name Li Cheng.

3

Sogdian tombs have also been found in other Chinese cities, including Guyuan, Ningxia, and Taiyuan, Shanxi.

4

These tombs show how immigrants to China, mostly Sogdian, adjusted to—and modified—Chinese cultural practices. While the traditional method of burial in Sogdiana was to expose the bodies of the deceased before placing them in either an ossuary or an aboveground naus structure, the Sogdian tombs found in Xi’an are Chinese in style, with a sloping walkway leading to an underground chamber, and often hold a Chinese-language epitaph giving a brief biography of the deceased.