The Story of Rome (15 page)

Unable to see what he was doing with his sword, as well as unable to avoid the thrusts of his foe, the Gaul tried in vain to get rid of the bird.

At length, worn out with the unequal struggle, the barbarian fell, and Valerius was hailed as victor.

The crow, as though content with the result of the battle, now flew away and was seen no more; but from that time Valerius was called Corvus, corvus being the Latin word for a crow.

After the victory of Camillus, the Gauls left Rome undisturbed until the end of the third Samnite war, in 290

B

.

C

.

About the Samnite wars I am now going to tell you.

CHAPTER XLI

The Dream of the Two Consuls

T

HE

Samnites were a rough and hardy race of warriors, whose homes were among the mountains of the Apennines.

In 343

B

.

C

.

they determined to wrest Campania, in the south of Italy, from the Romans.

The wars of the Samnites lasted for many long years, and when at length Rome conquered, she was mistress of Italy. But before she was victorious, the first, second, and third Samnite wars had been fought and won.

Of the first Samnite war little is known, save that it lasted for three years, and that the Romans won three battles.

During this first war, however, the Latins, who had allied themselves with Rome, revolted. They wished to be given the full rights of Roman citizens, and they demanded that one Consul, as well as half the members of the Senate should be Latins. Nor was this all. For they refused to be content unless Latium and Rome were henceforth counted as one Republic.

The Romans did not for a moment dream of granting such ambitious demands. Indeed, they resolved to punish the Latins for their presumption in making such large requests.

So they went to war and fought, until the Latins lost their last stronghold and were forced again to submit to Rome.

The Latins had gained little by provoking their former allies, for while some Latin cities were granted the rights of Roman citizens, all were forced to send soldiers to the Roman army.

Two famous stories are told of the war with the Latins.

The armies had encamped near to each other on the plain of Capua, in the south of Italy.

Manlius Torquatus was one of the Consuls, and he, with his colleague, had given strict orders that no soldier was to engage in single combat.

But the son of Torquatus chanced to be challenged by one of the enemy, and the temptation to fight was more than the young man could stand.

Was he victorious, what glory he would win! Was he beaten, he could but die! So, despite the strict order of the Consuls, young Manlius accepted the challenge.

Groups of Roman and Latin soldiers watched the combat with the keenest interest, and when at length, after a gallant fight, Manlius slew his opponent, a shout of triumph arose from his comrades. But the Latins looked on, sullen and ashamed, while their champion was stripped of his arms.

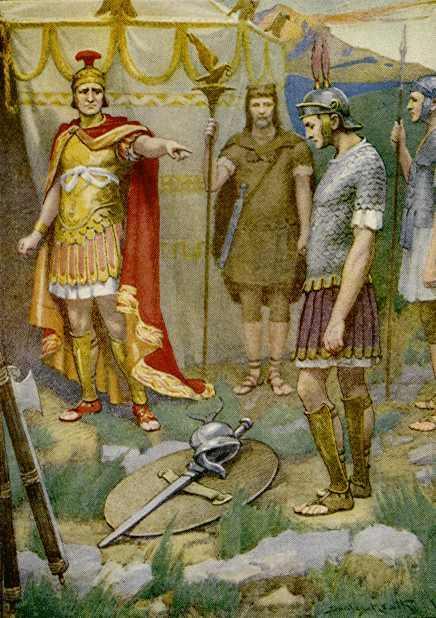

Flushed with victory, and thinking that his father would forgive his disobedience, the youth hastened to the tent of Torquatus, and laid the arms he had taken from his foe at this father's feet.

The youth laid the arms he had taken from his foe at his father's feet.

But discipline was dear to the Consul's heart, and he did not greet his son as he entered the tent, but turned coldly away from him. Had it been any other who had disobeyed, punishment swift and sharp would have descended on the culprit.

It made Torquatus angry to think that he should dream even for a moment of being more merciful to his own son than to another. He loved discipline, but he loved his son as well. So it was with a mighty effort that he resolved that, although it was his own son who had transgressed, punishment swift and sharp should be inflicted on him.

Cold and stern, the Consul's voice rang out, bidding the soldiers assemble in front of his tent, and there, before them all, he ordered that his son should be beheaded.

No one dared to dispute the order of the Consul, and the soldiers looked on in horror while their brave young comrade was put to death because of his disobedience.

The soldiers hated Torquatus for his severity, and never forgot it. But if they hated, they also feared, and never again were his commands disobeyed.

The second story is about a terrible battle that was fought close to Mount Vesuvius.

It was the night before the battle that the two Consuls, Torquatus and Decius Mus, both dreamed the same dream.

A man taller than any mortal appeared to each of the Consuls, and warned him that in the battle which was to be fought, both sides must suffer, one losing its leader, the other its whole army.

In the morning, when the Consuls found that each had dreamed exactly the same dream, they determined to appeal to the gods. Even as their dreams were alike, so also was the answer each received.

"The gods of the dead, and earth, the mother of all, claim as their victim the general of one party and the army of the other."

At all costs the Roman army must be saved. Of that neither Consul had any doubt. Nor did they shrink when they realised that to save the army one of them must perish.

So Manlius and Decius Mus agreed that the one whose legions should first give way before the enemy should give himself up to the gods of the dead.

When the battle was raging most fiercely, the right wing of the Latins compelled one of the Roman divisions to give way. The leader of the division was Decius Mus.

Without a murmur, the Consul prepared to fulfil the agreement he had made with Torquatus. By doing so he was sure that he would save the army from destruction.

Turning to a priest who was on the battlefield, he begged to be told how best to devote himself to the gods.

Then the priest bade Decius Mus take the toga that he wore as Consul, but which was not usually seen on the battlefield, and wrap it round his head, holding it close to his face with one of his hands. His feet the Consul placed on a javelin, and then, as the priest bade, he prayed to the god of the dead.

"God of the dead, I humbly beseech you, I crave and doubt not to receive this grace from you, that you prosper the people of Rome with all might and victory; and that you visit the enemies of the people of Rome . . . . with terror, with dismay, and with death.

"And, according to these words which I have spoken, so do I now, on behalf of the Commonwealth of the Roman people . . . . devote the legions and the foreign aids of our enemies, along with myself, to the god of the dead and to the grave."

When he had prayed, Decius Mus sent his lictors to tell Manlius what he was about to do.

Then, with his toga wrapped across his face, the noble Roman leaped upon his horse, and fully armed, plunged into the midst of the Latin army and was slain.

Inspired by the courage of Decius Mus, and knowing that the vengeance of the gods would now fall upon their enemies, the Romans fought with fresh courage.

At first the Latins were dismayed and driven backward. But they soon rallied, and fought so fiercely that it seemed as though the sacrifice of the Consul had been in vain.

But just as the Romans were beginning to give way, Manlius with a band of veterans rushed to their aid, and with loud cheers dashed upon the enemy.

The Latins, already weary, were not able to withstand this new shock. So the Romans were soon victorious, and slaughtered or took prisoners nearly a fourth part of the Latin army.

Torquatus now returned to Rome, expecting to receive a great triumph. But the citizens looked on his procession in silence and dislike, for he had come back from battle without his colleague.

In this the Romans were unjust to Torquatus, for had his legions been the first to flinch before the enemy, he would have faced death as bravely as did Decius Mus.

CHAPTER XLII

The Caudine Forks

O

NE

of the chief events of the Second Samnite war took place in 321

B

.

C

.

, at a gorge or pass called the Caudine Fork.

Gaius Pontius, the general of the Samnite army, was encamped at Caudium. He had hoped to hold the passes which led from the plain of Naples to the higher mountain valleys among the Apennines.

But one day he thought of a better plan. If he could but entice the Roman army into the mountain passes, he would have them in a trap before they were aware.

So he sent two countrymen to Rome, bidding them report to the Consuls that the Samnite army had left Caudium and marched to Apulia, where they were besieging the town of Luceria.

The Consuls had no reason to doubt the truth of the countrymen's words, and as Luceria was held by allies of Rome, they resolved to send an army to her help, lest she should fall into the hands of the enemy.

So before long the Roman legions were marching toward Apulia. As the shortest way lay through the pass of the Caudine Forks, and as the Consul Postumius, who was at the head of the legions, believed that the Samnite army was far away, he did not hesitate to enter the gorge.

It was a deep and gloomy pass, between rugged mountains. As the Romans advanced, the gorge grew more narrow and precipitous, and they were glad when at length they approached the end of the dangerous path. But their pleasure was soon changed to anxiety, for the exit from the pass was barricaded with trees and great masses of stone.

Postumius began to suspect treachery. It was plain that the trees had but recently been cut down. Suppose the barricades were the work of the Samnites! The Consul at once ordered the army to retreat.

But long before the weary legions reached the opening by which they had entered the pass they felt sure that they were caught in a trap.

The Samnites were indeed guarding the entrance, and escape was impossible.

Nevertheless, the Romans made a gallant attempt to scale the side of the steep mountains that brooded over the gorge, and when they reached the opening they even tried to make their way through the enemy. But the Samnites killed or wounded all who tried to escape.

When night fell, Postumius ordered his army to encamp in the valley at its broadest point, and here he awaited the will of Gaius Pontius.

But the Samnite general was in no haste to make terms with his prisoners. Each day that he delayed, famine would stare the Roman army more closely in the face. Before long it would be forced to agree to whatever terms he chose to dictate.

And, indeed, before many days had passed, the Romans were compelled to yield, crying to their foes: "Put us to the sword, sell us as slaves, or keep us as prisoners until we be ransomed, only save our bodies, whether living or dead, from all unworthy insult."

It was plain that the Romans feared lest they should be treated in the same way as they used their captives.

For the Romans dragged their prisoners in chains at the chariot wheels of their victorious generals. Often, too, their captives were beheaded in the common prison, and their bodies refused the rite of burial.

But Pontius used his power generously. If his terms were heard, yet they were just, and had in them no trace of cruelty.

"Restore to us," said the Samnite general, "the towns you have taken from us, and recall the Roman colonists you have unjustly settled on our soil. Then conclude with us a treaty, which shall own each nation to be alike independent of the other. If you will swear to do this I will spare your lives and let you go without ransom, each man of you giving up your arms merely and keeping his clothes untouched, and you shall pass in sight of your army as prisoners, whom we . . . . set free of our own will, when we might have killed them, or sold them, or held them to ransom."

The Consuls and officers of the army vowed to observe this treaty, and six hundred knights were given as hostages to the Samnites.

But Pontius, had he been wise, would have gained the consent of the Senate and people of Rome to his terms, before he was content.

To the Romans, the demands of Pontius seemed severe, but yet deeper was the humiliation they were to endure.

The entire army, along with the Consuls, were forced to pass beneath the yoke, in the presence of their foe. It was the only way of escape from the pass of the Caudine Forks.

Giving up their arms, and wearing only a kilt which reached from their waist to their knees, the vanquished army filed sullenly out of the gorge beneath the yoke.

This was no unusual humiliation, but was the custom in those days, and equal to our demand that arms should be laid down on the surrender of a garrison.

Pontius was indeed strangely kind to his conquered foes, ordering carriages for the wounded, and giving them food to eat on the march back to Rome.

But nothing could comfort the Romans, whose pride had been gravely wounded by being forced to pass beneath the yoke.