The Success and Failure of Picasso (24 page)

Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

78

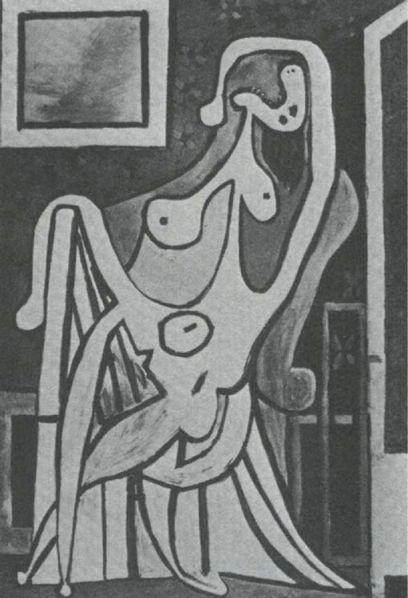

Picasso. Figure. 1927

The

Woman in an Arm-chair

is less distorted. Nobody can fail to see that this represents a woman. People may pretend to themselves that they can’t disentangle the figure, because it constitutes such a violent attack on their sense of propriety; but recognizing the attack, they also recognize the figure. Nevertheless, the painting is as absurd as the last one, and the subject has again been destroyed – although in a different way. The motive of the painting is no longer straightforwardly sexual, but far more bitterly and desperately emotional. It is for this reason that the physical displacements of the body are far less extreme, but the overall effect more violent. There is no Venus behind this picture; rather one of the Seven Deadly Sins, feared, resented, and yet undismissible. It is absurd because, removed from the medieval context of Heaven and Hell, the violence of the emotion conveyed and yet not explained and not related to anything else, destroys our belief in the subject. It is perfectly possible to believe that Picasso felt like that, but we cannot share this feeling with him because it cannot be understood or evaluated on the evidence of what he shows us. We have no way of telling whether it is noble anger or petulance. All we can recognize is that

he

is disturbed. What disturbed him we do not know – because he has not been able to find the subject to contain his emotion.

79

Picasso. Woman in an Arm-chair. 1929

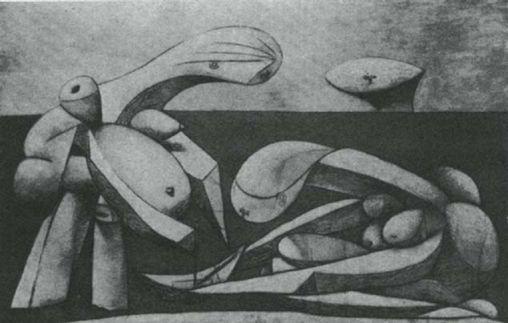

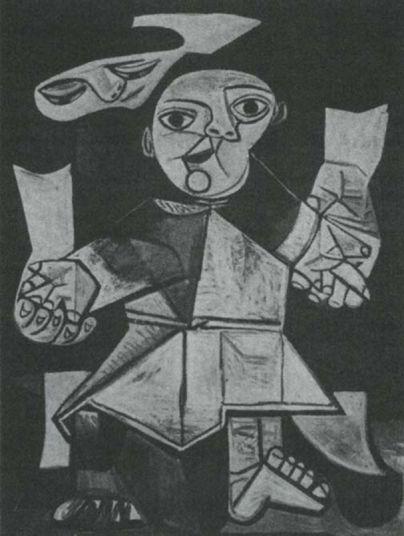

In

Girls with a Toy Boat

the problem is different. It isn’t now a question of Picasso being driven by a feeling or emotion which he cannot house in a subject; here he gives himself up to his own ingenuity, and the absurdity arises because he appears to

ignore

the emotive power of the forms with which he is playing. He is planning a new (and momentary) human anatomy, as schoolboys plan rockets or perpetual-motion machines. His method of drawing is very precise and three-dimensional, so that it would be quite easy to construct one of these figures out of wood or paper. This tangibility increases the absurdity. Such ‘real’ breasts, buttocks, and stomachs attached to such machines are bound to make us laugh in order to release the tension of the emotion provoked by the sexually charged parts and then belied by all the rest. A similar inconsistency is implied by the action. If they are children playing with a boat, why have they women’s bodies? If they are women, why the toy boat? It may seem naïve to ask such a logical question of a painting in which a head can peer over the horizon as though over the edge of a table. Of course Picasso was joking, trying to shock, playing at contradictions. But this was because he didn’t know what else to do. And the comparatively untransformed sexual parts, so inconsistent with the rest, are an indication of this indecision. Within three months of painting this picture, he was painting

Guernica

; it is worth comparing these figures with one of the figures there.

80

Picasso. Girls with a Toy Boat. 1937

81

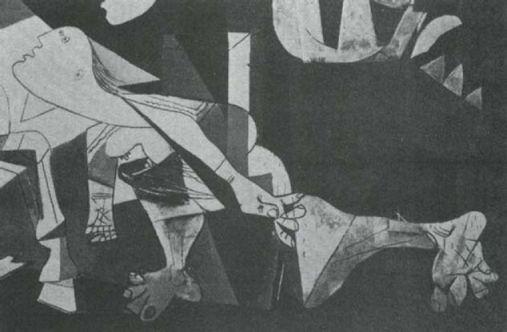

Picasso. Guernica (detail). 1937

Every part of the body of the woman in

Guernica

contributes to the same end; her hands, her trailing leg, her twisted buttocks, her sharp nipples, her craning head – all bear witness to what at this moment is her single ability: the ability to suffer pain. The contrast between the two paintings is extraordinary. Yet in many ways the figures are similar, and without the exercise of paintings like

Girls with a Toy Boat

Picasso would never have painted

Guernica

in the way he did. The difference is one of single-mindedness. Yet to be single-minded you have to know what you want. And for Picasso to know what he wants, he has first to find his subject.

82

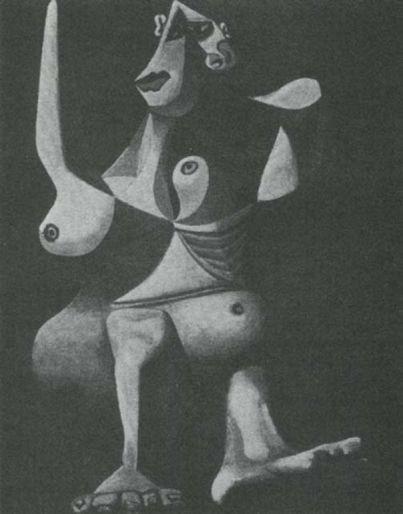

Picasso. Nude Dressing her Hair. 1940

Picasso painted the 1940 nude immediately after the defeat of France, whilst the German troops were occupying Royan, on the Atlantic coast, where he had fled. It is an anguished painting, and if one knows of the circumstances in which it was painted, it becomes an understandable picture. But it remains absurd, even if horrifically absurd. To see why this is so, let us again make a comparison with a successful painting. Both pictures are the result of the same experience – the experience of defeat, occupation, and a terrible vision of evil, which was in no sense metaphysical, but there in the streets in its jackboots and with its swastika.

83

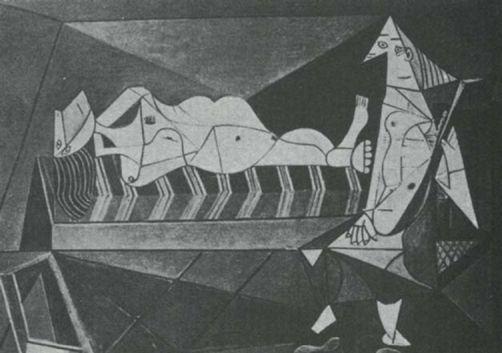

Picasso. Nude with a Musician. 1942

This second picture, painted two years later, is no more explicit about the general experience from which it derives, but it is self-contained and consistent. The experience has found a subject. The subject, baldly described in words, may seem unremarkable: a woman on a bed and another woman sitting on a chair, holding a mandolin which she is not playing. Yet in the relationship between these two women and the furniture and the room that closes in around them, without a window or a door, there is all the claustrophobia of the curfew and a city without freedom. It is like making love in a cell where there is never any daylight. It is as though the sex of the woman on the bed and the music of the mandolin had been deprived of all their resonance, because such resonance requires a minimum freedom within which to vibrate. The real subject is not simply the two women, but

the state of being confined in this room.

In Picasso’s mind, as he painted it, there must have been an image of such a room, an image of curfew, to which he could refer and through which he could express his emotion.

The

Nude Dressing her Hair

squats in an even more celllike room. But because there is no consistency between the parts (just as was the case with the

Toy Boat

) we are unable to accept the scene as a self-contained whole. None of the parts refers to each other: instead, each, separately, refers to us, and we then refer it back to Picasso. A normal mouth forms part of a slashed, displaced face. The underneath of a foot, seen as by a chiropodist, joins on to a butcher’s bone which ends in a stone stomach. It is true that the figure as a whole does pose one question: Is this a woman or a trussed fowl? And from that question we can deduce bestial indignities. But the question remains, as it were, rhetorical. We do not believe in the woman being a trussed fowl, we believe only in Picasso wanting to make her look like that. In the end we are left face to face with what seems to be Picasso’s wilfulness. And it seems thus because he has not been able to express himself, because he has not been able to include his emotion in his subject but only impose his emotion upon it.

Some may see the difference between these two paintings as principally one of style. In the

Nude with a Musician

there is stylistic consistency. The way an eye is rendered is compatible with the way a hand, a foot, or hair is rendered. All are equidistant from (photographic) appearances. In the other painting there is deliberate stylistic inconsistency. Yet the true difference is more profound than this. We can imaginatively enter the first picture and as we proceed, moving from one part to another, we gather emotion. In front of the

Nude Dressing her Hair

, we never get beyond the violence that each part does to the next. No emotion develops because it is short-circuited by shock. And that is exactly what happened when Picasso was painting it; he short-circuited his own emotion, because he could find no circuit for it through a subject. A woman’s body by itself cannot be made to express all the horrors of fascism. But Picasso clung to this subject because, at that moment of fear and crisis, it was the only one of which he felt certain. It is the earliest subject in art, and modern Europe had failed to give him any other.