The Success and Failure of Picasso (19 page)

Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

66

Giovanni Bellini. The Feast of the Gods. 1514

Other things could be said about this painting. As a kind of complement to its sentimentality, it also has wit. It works quite well as a decoration. But now more exaggeratedly and less consistently – Picasso chooses the primitive, the archaic.

He first made such a choice as a direct criticism of what he saw around him. An element of criticism still exists. In 1946

Joie de vivre

affirmed life, even if of an excessively innocent kind, in the face of a terribly war-scarred Europe. But now, from the age of sixty-five onwards, Picasso’s imagination begins to gravitate

naturally

towards the archaic. An attitude, once consciously held, has become a cast of mind.

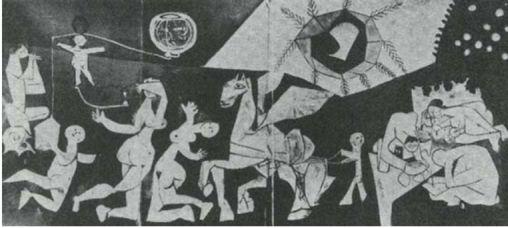

Thus, in 1951, when Picasso painted

Massacre in Korea

, the effect is almost the opposite of what he intended. The soldiers, despite their sten-guns, are so heraldic and archaic that either we lose the sense that this is a modern massacre, or else we consider the soldiers as symbols of an eternal, unchanging force of cruelty and evil. Either way our indignation, which the painting was meant to provoke, is blunted.

67

Picasso. Massacre in Korea. 1951

In 1952 Picasso painted one of his last major works on a theme of his own. Since then most of his paintings have been based on other artist’s pictures. The work consisted of two large panels:

War

and

Peace.

68

Picasso. Peace. 1952

The panel

Peace

can well stand as a late testament of Picasso’s. He has always been an artist concerned with men. He has never been an aesthete. And so in this panel we can read his comments, as an old man, on the human condition.

He is profoundly humanist – that is to say he believes the highest good is the happiness of man. In this picture (unlike the

Joie de vivre

) he suggests that culture is one of the conditions of this happiness. Such culture implies social organization. A woman reads a book. A man writes. Another plays pipes. A boy drives a horse. Two women dance. The scene is idyllic.

Yet what is remarkable is that there is no hint of the twentieth century in this vision. The objects which are included – an hourglass, a fish-bowl, a bird-cage, a reed pipe, the fire which the man on the right is making, the harness for the horse like one used for a plough – most of these actually suggest an earlier, simpler civilization.

And as if to emphasize this, there is then the magical element. The horse, like Pegasus, has wings. The sun has an eye. Birds fly in the fish-bowl, and fish swim in the birdcage.

Of course one must not interpret such a picture literally. One must allow for inherited symbols, outlasting the civilization of their origin. One must grant poetic licence. My point is that the poetry of this painting is simple, fantastic, legendary, and, as it were, proverbial. It belongs to the tradition of folk stories and nursery rhymes:

I saw a fishpond all on fire

I saw a house bow to a squire

I saw a balloon made of lead

I saw a coffin drop down dead

I saw two sparrows run a race

I saw two horses making lace

I saw a girl just like a cat

I saw a kitten wear a hat

I saw a man who saw these too

And said though strange

They all were true.

It is a painting which, to make us imagine peace and happiness, encourages us to believe in innocence rather than experience. Let us look at Picasso’s

Peace

beside two other paintings.

Titian’s

Shepherd and Nymph

is also an old man’s vision of an idyllic world. It is also set in a kind of Arcadia with a shepherd and his pipes. Yet there is no question here of this couple belonging to a simpler civilization. Everything about them suggests sophistication (look at the woman’s hand and the quality of her skin) and experience: experience which, by its very nature, must include a sense of time

passing, hence the way she turns and he leans, as though both recognize that they must soon move. It is a vision whose beauty and spell depend upon the acceptance of change. The change when she turns round. The change when he, a moment ago, stopped playing. The change when he, in a minute, will move towards her. The change as the light fades. The change when she is dressed. It is a painting which, although it is nostalgic because Titian is old, affirms the maximum possible awareness of the world, the maximum possible experience of change.

69

Titian. Shepherd and Nymph. c. 1570

It is always difficult to compare works of art across the centuries: the degrees and growing points of hope and fear differ so much. The Titian is largely an affirmative picture. Among modern works it makes me think of a poem by Yeats which is far more melancholy but which deals with the poet’s consciousness of the same kind of experience. I quote it in contrast to the innocence of the nursery rhyme.

‘Love is all

Unsatisfied

That cannot take the whole

Body and Soul’;

And that is what Jane said.

‘Take the sour

If you take me

I can scoff and lour

And scold for an hour!’

‘That’s certainly the case,’ said he.

‘Naked I lay

The grass my bed;

Naked and hidden away

That black day’;

And that is what Jane said.

‘What can be shown?

What true love be?

All could be known or shown

If Time were but gone.’

‘That’s certainly the case,’ said he.

By comparison with the Titian, the dancing figures in the Picasso, for all their violent movements, are quite static. And because they are static, and ‘Time is gone’, they are innocent.

The other painting which it may be useful to put beside Picasso’s

Peace

is a modern one: the

Composition aux deux perroquets

by

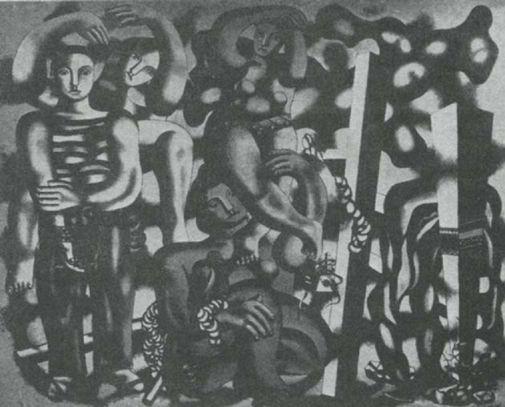

Fernand Léger.

70

Léger. Composition aux deux perroquets. 1935–9

One of the main themes of

Léger’s later work was Leisure. A day out in the country. This brought Léger quite close to the Renaissance idea of Arcadia. And for Léger, like the Renaissance artists but unlike Picasso, this Arcadia had to be modern, had to be an idealization of the present. The Renaissance Arcadia was a vision of the courtly life freed from the intrigues of the city. Léger’s Arcadia is a vision of the modern world granted plenty and a twenty-hour week.

And how naturally – even in an ‘unrealistic’ figure composition – Léger maintains contact with the modern, industrialized world! His figures never slip away out of history into timelessness like Picasso’s do. The man’s shirt is machine-made. The posts which reach up to touch the clouds are twentieth-century architectural units. The ropes might be made of nylon. The miracles are no longer mysterious (like the fish in the bird-cage) but the result of human control. For Picasso, acrobats have always been wandering players who belong nowhere and are never still. For Léger, acrobats were builders who made constructions of their bodies to transcend nature and gravity. For Picasso their appeal lay in their elusiveness. For Léger it lay in their collective skill. The implication of this painting is that everything ought to be able to be controlled and constructed for man’s pleasure – even the clouds in the sky.

16