The Success and Failure of Picasso (30 page)

Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

106

Picasso. Bullfight. 1934

The violence, it seems, is only to rob Velazquez: to honour him perhaps at the same time as robbing him; even – and again like a child – thus to ask for his protection. In his own painting Velazquez is so effortlessly himself, and in Picasso’s painting he is so overwhelmingly large, that he might be a father. It may be that as an old man Picasso here returns as a prodigal to give back the palette and brushes he had acquired too easily at the age of fourteen. Perhaps this last large painting of Picasso’s is a comprehensive admission of failure. Perhaps this is only a minute

part of the truth, or none of it at all. But what is certain is that neither Picasso’s

Las Meninas

nor any of his late paintings are the mature work of an old painter, at last able to be himself. What is certain is that Picasso is a startling exception to the rule about old painters.

Why has nobody pointed this out? Why has nobody considered Picasso’s likely desperation? Apparently it is not only in his own household that nobody dares to mention the word failure. Apparently we need to believe in Picasso’s success more than he does himself.

Towards the end of 1953 Picasso began a series of drawings. At the end of two months there were 180 of them. Drawn with great intensity, they are autobiographical; they are about Picasso’s own fate.

When they were first exhibited and published, their general character was recognized. Besides praising the ‘exquisite use of line’, people talked of an ‘emotional disturbance’, etc. But then,

in order not to understand what the drawings confessed

, everyone pretended that their meaning was so complex and mysterious and personal that it would be impertinent to try to put it into words. Enough to declaim once more: Picasso! And after having admired the brilliance, to forget everything but his ‘greatness’. (The greatness that had ground him to a standstill.)

It is true of course that for Picasso each of the drawings must have had several levels of meaning and hundreds of stray associations. But it is equally true that the theme of the confession as a whole is quite unambiguous.

In nearly every drawing there is a young woman. Not necessarily the same one. Usually she is naked. Always she is desirable. Sometimes she is being painted. But when this happens, one scarcely feels that she is posing. She is

there

– just as she is

there

in the other drawings; her function is to be. She is nature and sex. She is life. And if that sounds a little ponderous, remember that it is for the same elemental reason that all drawing classes from the nude model in all art schools are called Life Classes.

Beside her Picasso is old, ugly, small, and – above all – absurd. She looks at him not unkindly, but with an effort – as though her concerns were so different from his that he is almost incredible to her.

He struts around like a vaudeville comedian. (The comparison I made a few pages back is one that has occurred to Picasso too.) She waits for him to stop.

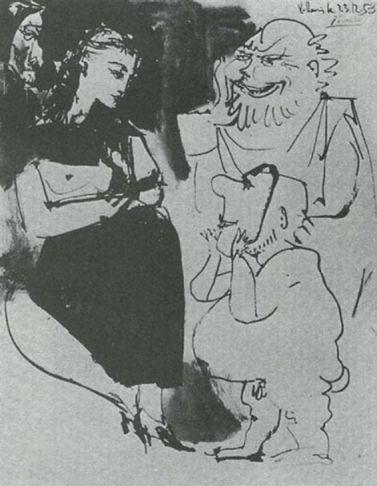

107

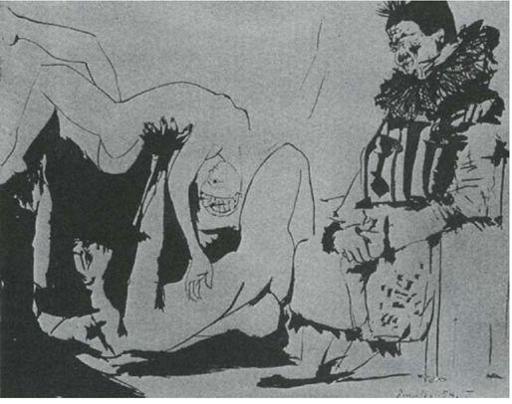

Picasso. Nude and Old Clown. 21 December 1953

To hide himself and at the same time to mock himself he puts on a mask. The mask emphasizes that whereas all her pleasure in physical being and in sex is natural, his, because he is old, has become obscene. Next to the young woman is an old one. In another drawing the young and the old women sit side by side. Picasso is confessing his horror at the fact that the body ages and the imagination does not. When the whole energy of life has been found in the form of resilience of a body – how is it possible to endure the continuing need for that consoling energy when the form begins to collapse?

108

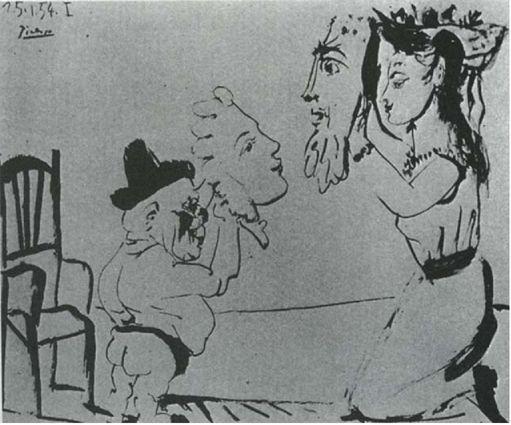

Picasso. Young Woman and Old Man with Mask. 23 December 1953

He begins to envy the monkey – the monkey who so early in Picasso’s work was a symbol of freedom. He envies it because the young woman plays with it. But, more profoundly, he envies it because, unselfconscious, it pursues its desires without any sense of absurdity: on the contrary, with a complete sense of absorption which then, despite the ugliness of its body, compels the young woman to delight in it.

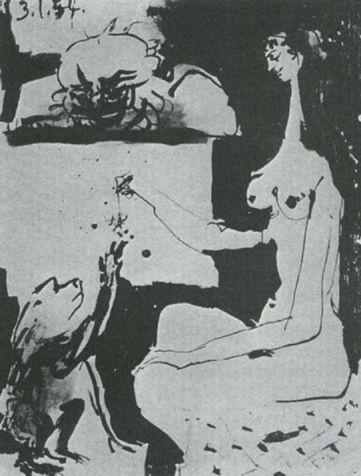

109

Picasso. Young Woman and Monkey. 3 January 1954

He returns to the idea of the mask, this time seeking comfort from the conceit that it is his old age which is the mask: and that behind it he is as young as ever. A young Cupid holds the mask in front of him. It represents both the old man’s face and his genitals: a pun which Goya used in some of his etchings and which Picasso surely remembered, but also a lonely, nostalgic variation on the theme of that composite lover’s head whose sweet smile was once all sexual pleasure.

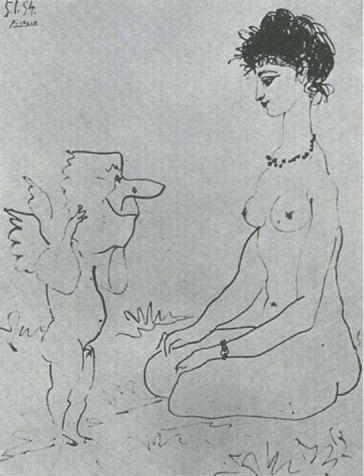

110

Picasso. Young Woman and Cupid with Mask. 5 January 1954

The Cupid, with the old man’s face and organ, courts her.

The race, the panting begins. Again the absurdity, the slavery of the situation haunts Picasso.

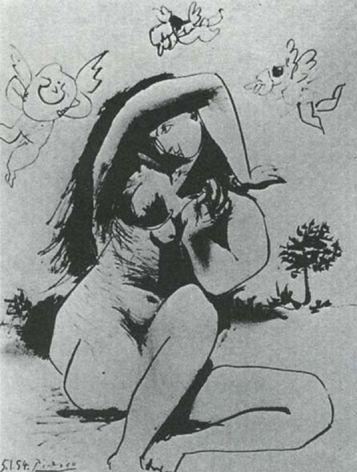

111

Picasso. Young Woman with Cupids. 5 January 1954

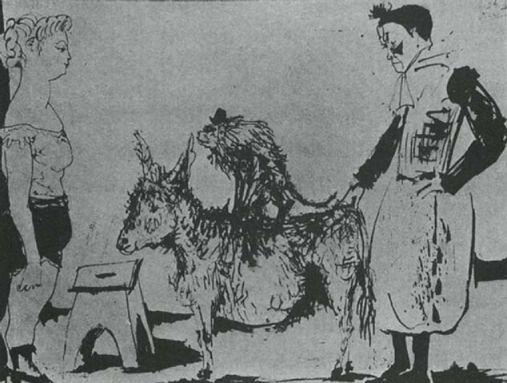

He draws a monkey, like a jockey, riding a horse. Then a woman, like Godiva, riding a toy horse. Later, in a world where everything is soiled, the monkey jerks himself up and down on a donkey’s back whilst a clown and a girl acrobat gaze as though sadly accepting as a truth such pointless slavery to sex.

112

Picasso. Girl, Clown, Donkey, and Monkey. 10 January 1954

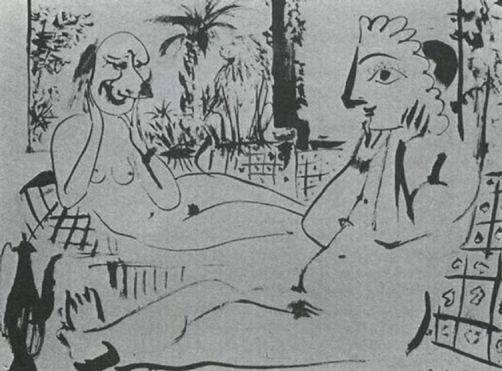

To escape from the slavery Picasso thinks again of the pleasures. Summoning up the acrobats of his youth, he turns their ease into a metaphor of free enjoyment.

The memory of such happiness rides him on remorselessly.

113

Picasso. Old Clown and Couple. 10 January 1954

Now he grasps at that shared subjectivity which is unique to sex and to which he had dedicated so many paintings. By the logic of this sharing she will wear his mask – the old man’s crumpled one – and he will wear her mask, eye open and fringed with lashes. Here, if the picture could become reality (and metaphorically it could), is true happiness. The horror is that the monkey remains. He sits there behind them and looks away because such sentimental illusions are of no interest to him. They have no substance and no weight.