The Success and Failure of Picasso (29 page)

Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

Unfortunately we cannot create even in our minds the Picassos that have not been painted. Picasso hates travelling. He has, for instance, only been to Italy once. He has never left Europe. But the opportunities were so wide, and at first Picasso’s enthusiasm for a new life, a new struggle, was also so great!

It could have been the first time in the history of art that an artist was commissioned according to the needs of his own genius. The paintings, by the simple fact of being painted, could have given substance to a thought, a hope of Aimé Césaire’s, which is fundamental to our time:

…for it is not true that the work of man is finished

that we have nothing to do in this world

that we are the parasites of our world

that all we must do is keep in step with the world

no the work of man has only just begun

and it remains for man to conquer all the restrictions standing so firm at the corners of his fervour

no race has the monopoly of beauty, intelligence or strength

there is room for all at the meeting place of conquest.…

Above all, these works, which do not exist, could have meant the triumph of a great artist’s late period – the full use of Picasso’s genius at the height of its power.

As it was, he became a national monument and produced trivia.

The mounting horror of the last fifteen years of Picasso’s life can be glimpsed between the lines of all those who, having visited the monument, write down their impressions for newspapers. All that they have to offer is gossip. Even a serious scholar like

John Richardson is reduced to describing what Picasso wears and eats for breakfast. In the end one is forced to accept that there is nothing else to describe. Why then describe it? Because Picasso is a celebrity, floodlit with a lighting that from the spectator’s point of view makes everything significant. People, and even genuine friends of his, press near so that some of the light can fall on their faces too.

If you should wish to know of the horror of such a life in detail, I recommend the book

Picasso Plain

by

Hélène Parmelin.

1

Most of what it reveals is unintentional. The author is the communist wife of a communist painter and a close friend. The book is about Picasso’s life in the fifties. It is dedicated to

the King of La Californie

. La Californie was Picasso’s house in Cannes. Picasso is the King.

Picasso is the king. Everything and everybody revolves round him. His whim is law. No word of criticism is ever heard. There is a great deal of talk but very little serious discussion. Picasso behaves and is treated like a child who has to be protected. It is perfectly in order to like one picture better than another. But it is inconceivable that anybody should suggest that any painting is a total failure. There is no sense whatsoever of a struggle towards an aim: only a sense of Picasso struggling blindly within himself, and everybody else struggling to keep him amused and happy. Manners are informal but the degree of self-abnegation byzantine. Madame Parmelin tells a story that demonstrates this – almost incredibly. She was having a bath in a room off Picasso’s studio. Unexpectedly he returned with some visitors. She had no clothes with her and the only way out was through the studio. Rather than shout and ask for a towel she sat shivering for three quarters of an hour and caught influenza.

The horror of it all is that it is a life without reality. Picasso is only happy when working. Yet he has nothing of his own to work on. He takes up the themes of other painters’ pictures (Delacroix’s

Femmes d’Alger

, Velazquez’s

Las Meninas

, Manet’s

Déjeuner sur l’herbe

). He decorates pots and plates that other men make for him. He is reduced to playing like a child. He becomes again the child prodigy. The world has failed to liberate him from that state because it has failed to encourage him to develop.

Outside his studio it is no more real. In his house he is surrounded by acolytes and flatterers. Outside his house he is a benign god who brings luck to all those who are living in the same town or dining in the same restaurant. But who among them takes him seriously? As a communist? As a painter for them? He is liked, perhaps even loved, because he is a benefactor; he brings honour and prosperity; he gives away autographs and drawings and the chance of having spoken to him.

To fill the vacuum left by reality, it is necessary to invent. His life is full of fantasies and specially created dramas. I do not speak of his subjective life, but the daily life in his household. There are invented characters, invented rituals, invented turns of phrase. Nothing, as it were, remains standing on the floor. Everything is lifted up and made ‘truer than life’ by his devotees, so that he shall never feel lost in emptiness. One is reminded of the last days of some old vaudeville star: everything, creaking now, is still

invented

as superlative. But there is one great difference: old vaudeville players go on performing till they drop. The tinsel is to keep them going, not to distract them.

So complete is the loss of reality and so frenetic are the efforts of all those around him to keep him feeling and being great that Picasso himself is no longer believed. A man who has trusted his own sensations as he has done knows the extent to which things have gone. He is desperate. The last thing he says in Parmelin’s book is: ‘You live a poet’s life and I a convict’s.’ But she, in her usual state of euphoria induced by believing that she is the great man’s confidante, thinks that this is just Picasso being Picasso.

At this point I may be accused of being too imaginative. I talk of pictures that Picasso

might

have painted in India. I describe to you Picasso’s inner state of mind without having met him and in the face of the evidence of those who write about him as friends. My justification is that what I have deduced is the result of trying to relate

all

the facts that can be publicly known about Picasso. So often important ones are hidden or ignored.

Painters, unlike a certain kind of poet, need time to develop and slowly uncover their genius. There is not, I think, a single example of a great painter – or sculptor – whose work has not gained in profundity and originality as he grew older. Bellini, Michelangelo, Titian, Tintoretto, Poussin, Rembrandt, Goya, Turner, Degas, Cézanne, Monet, Matisse, Braque, all produced some of their very-greatest works when they were over sixty-five. It is as though a lifetime is needed to master the medium, and only when that mastery has been achieved can an artist be simply himself, revealing the true nature of his imagination.

102

Delacroix. Les Femmes d’Alger. 1834

However favourably one judges Picasso’s

work since 1945 it cannot be said to show any advance on what he created before. To me it represents a decline: a retreat, as I have tried to show, into an idealized and sentimental pantheism. But even if this judgement is mistaken, the extraordinary fact remains that the majority of Picasso’s important late works are variations on themes borrowed from other painters. However interesting they may be, they are no more than exercises in painting – such as one might expect a serious young man to carry out, but not an old man who has gained the freedom to be himself.

103

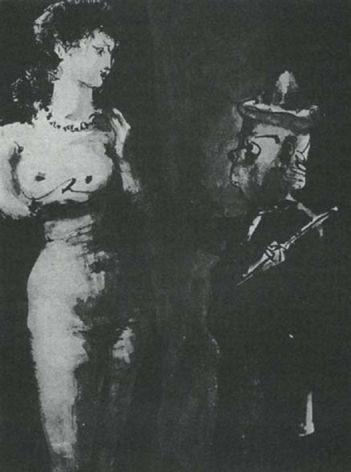

Picasso. Les Femmes d’Alger. 1955

104

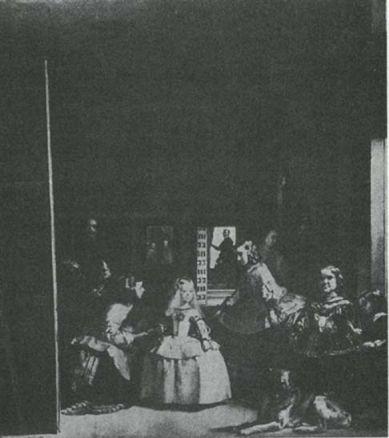

Velazquez. Las Meninas. 1956

105

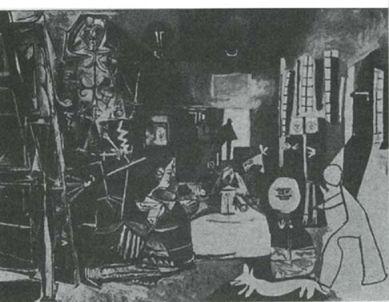

Picasso. Las Meninas. 1957

It is sometimes claimed that Picasso only takes Delacroix or Velazquez as a starting point. In formal terms this is true, for Picasso often reconstructs the whole picture. But in terms of content the original painting is even less than a starting point. Picasso empties it of its own content, and then is unable to find any of his own. It remains a technical exercise. If there is any fury or passion implied at all, it is that of the artist condemned to paint with nothing to say.

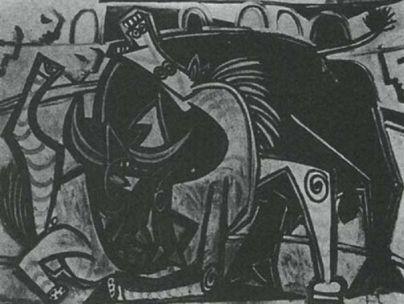

Notice in his variation on the Velazquez how extreme the distortions and displacements are. The dwarf, the dog, the painter are wrenched out of Velazquez’s hands – but for what reason, to express what? One has only to compare any of these figures with the

Bullfight

, painted twenty years before, to be reminded of how intensely Picasso once used distortions to communicate experience.