The Suitors (30 page)

Authors: Cecile David-Weill

“Oh, you must, that’s the

l

in Revlon: there was Charles Revson and Charlie Lachman …”

I thought I saw Alvin wince in distaste at the bowl of shelled peanuts into which we were all happily plunging our hands for a nibble, which suggested that hygiene was clearly one of his pet peeves, but before I could ponder his reaction any further, Nicolas and Vanessa made their entrance onto the terrace.

Since Nicolas had come often to L’Agapanthe when we were together, Vanessa had been informed of our house rituals regarding dressing for dinner, and she had gone all out. What’s more, this was a woman who, living in Manhattan, habitually dressed to the nines for a little dinner in a corner bistro.

She was wearing a very short baby-doll dress in red organza and bronze shoes like a web of laces that added another six inches to her already endless legs. And the combination of her slyly “innocent” dress and her bewildering shoes startled our gathering into an eloquent silence. Unless we were, quite simply, stunned by her beauty. Because beauty is a strange thing, exciting stupor and fascination more often than desire. And Vanessa seemed used to seeing her beauty freeze timid men and neurotic women—when it didn’t provoke such bedazzlement that those around her just stared, deaf and dumb.

I imagined how frustrated she must feel by thinking of my son, who was often both pleased and angry that I loved him too much to love him properly whenever I found myself distracted while listening to him, overcome by the joy of seeing him, there in front of me, so healthy and so handsome.

Vanessa must have had real personality to want so much to cut through the screen of blinding beauty that obscured her, I thought, as I watched her make an effort to get us to talk to her and return to our conversations, but the poor thing could not keep us from gazing at her. Even worse, Odon started talking about beauty itself.

“Do you agree with Allison Lurie’s idea that beauty, far from provoking desire, more commonly inspires love?”

That was too much for Vanessa, who blushed and began to stammer, but Nicolas came to her rescue.

“I agree wholeheartedly, my dear Odon, because I’m head over heels in love with my wife. Now, has Alvin told you that he’s the champion of air rights?”

“Madame, dinner is served!” bellowed the head butler.

“

Air rights?

What are they? You must tell us all about them over dinner,” said my mother, rising to lead the way.

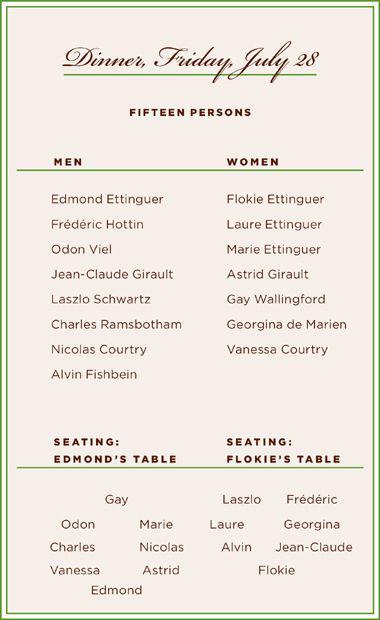

MENU

Soufflé Mornay

Sole Murat

Salad and Cheeses

Mille-feuille with Raspberries

Dinner began in general confusion. Alvin thought we were crazy when he saw our reaction to the tables in the dining room, which the new head butler had decorated with his disastrous floral arrangements. He had also seen fit to set out plastic bottles of mineral water in order to avoid having to serve us from our silver carafes! Although our American guest definitely disapproved of the plastic bottles, which offended him more from the ecological than the aesthetic point of view, he found the vases of cacti and weathered wood very New Age, in a Sedona, Arizona, sort of way, and he rather liked them. What he really didn’t understand, however, was why our animated conversation took place mostly after the butlers had left the room, like those secret confabs in children’s camps and boarding schools after lights-out,

when the volume of noise varies according to the proximity of adult supervision.

As for my mother, she made an effort not to take offense over Alvin’s worries about the menu, because although he had obviously decided to eat what was put in front of him without making a fuss, he was finally compelled to ask, “Are the eggs organic?”

Finding his question absurd, since—organic or not—the chef always bought the best products at the market, my mother bluffed without blinking an eye: “Absolutely.”

She almost lost patience, however, when Alvin asked her if he might have an egg-white omelet instead of the delicate marvel of eggs, butter, béchamel, and Gruyère on abase of impeccably soft-boiled eggs soon to be placed before us and which never failed to elicit cries of admiration from the most hard to please of our guests, such was the skill required to bring a soufflé Mornay to perfection. Then, rallying to her initial open-mindedness toward this new guest, my mother rose to the occasion: “Why not!”

“So, these air rights?” asked Laszlo brightly, to lighten the atmosphere.

Alvin explained that after making his fortune in toys, he had moved onto real estate and dealt a great deal

in the rights to use and develop the empty space over buildings in New York.

“I don’t understand. Who would be interested in them?”

“Well, developers intending to put up buildings taller than the limit anticipated by the local zoning map. Because all a developer needs to do is buy the air rights over adjacent buildings and turn their space into extra stories for the building he wishes to construct.”

“You mean that the lower the neighboring buildings are, if they’re small houses, for example, then the more air they have to sell, and the higher the developer can build?”

“Exactly.”

“Unbelievable … and how much does the open airspace cost?” asked Laszlo.

“Between 213 and 430 dollars a square foot, let’s say 50 to 60 percent of the sale price of a plot.”

Frédéric was electrified. “But that’s a gold mine, your angle! Because I figure that, if they have the choice among several adjacent properties whose airspace they can buy, the developers must set all the neighbors against one another and force them to accept an offer that is nonnegotiable.”

“Yes,” continued Alvin, “unless on the contrary the potential seller finds himself in a solid position as the

key to the developer’s entire project, which requires that he purchase not only his air rights but those of all his neighbors.”

“Ah! Because that can go on ad infinitum?”

“No, only within the framework of one city block.”

“Fascinating …”

“Oh, wonderful, filet of sole Murat, I love that!” exclaimed Jean-Claude, taking a generous helping of fish, potatoes, and artichokes from the proffered serving dish.

“Do you eat like this every day?” asked Alvin, in the mixture of surprise and indignation adopted by an American citizen who sees someone throwing something on the ground or cutting in line.

“Yes, why?” replied my mother, honestly surprised.

“But it’s such a rich diet, I don’t see how you can stand it …”

Alvin then delivered a minutely detailed rundown of the calorie counts in our dinner, followed by a dietetic sermon on one’s ideal weight, a screed that entailed deep discussion of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, vegetarian diets, omega-3 benefits, oils from fish, argan, and borage, flaxseed oil supplements, and iron pills—or better yet, iron in liquid form, to avoid constipation—and that brought us to the salad and cheese course.

My mother leaned toward Jean-Claude to tell him just what she thought of this nonsensical chemical babbling. “Rich! Rich! In the first place, we eat chicken, fish, or pasta, not proteins or hydrates of carbon, whatever that means!”

My mother was about to explode, while the rest of us were succumbing to boredom like a congregation benumbed by a Sunday sermon. And since it was easier and more courteous to change the subject instead of trying to shut him up …

“Alvin, I fear you are talking to a brick wall. Why don’t you talk to us about your interest in yoga?” I asked.

Alas, we realized that we were in for another dose of pontification when he announced that “diet and yoga are linked, because digestion requires a level of energy incompatible with …”

So we were treated to a course on Jivamukti yoga while Marcel served us the mille-feuille with raspberries.

“Five thousand years ago, India gave birth to yoga, which means ‘union’ in Sanskrit. Its goal is to attain an understanding of the interdependence of all forms of life …”

Too beaten down even to consider reacting, we simply relaunched him now and then so we could eat our dessert in peace.

“Yes, but what about Jivamukti?”

“It was created in 1984 in the United States. And it shifted the practice of yoga in America from an esoteric ritual observed by a few initiates to a discipline followed by sixteen million Americans.”

Suiting the action to the word, Alvin began fiddling with the fingers of his right hand again, but this time with confident ease, as if he’d delivered this particular litany many times before.

“The definition of Jivamukti yoga is ‘liberation through life,’ meaning a way of being in the world. Reserved for those who seek to expend intense physical effort, it has won over such adepts as Sting, Christy Turlington, Donna Karan, and Gwyneth Paltrow.”

“But what

is

it exactly?” I asked gamely.

“There are five pillars of Jivamukti instruction …”

But instead of listening to Alvin, I was waiting for the moment when he would start ticking things off on his fingers, which he then proceeded to do.

“The first pillar, nonviolence or ahimsa, might be described as: recognize yourself in others, in humans as well as animals. The second pillar, devotion or bhakti, stipulates that we must offer all that we experience to a higher entity than ourselves. The third pillar, meditation or Dhyana …”

“Well, now, that’s certainly

much

clearer,” exclaimed Frédéric sweetly at the end of Alvin’s lecture, while the rest of us sat speechless.

Floored by Alvin’s virtue and gibberish, we were about to leave the table when the butler came to tell me that my son was on the telephone.

Wondering if he’d timed his call to reach me just after dinner, I went to the “phone booth” (it looked rather like a confessional) just outside the living room, in which you had to sit down on the banquette to activate the ceiling light.

“I can’t go to sleep, Mummy! Do you think it’s serious?”

At first I dealt with this lightly, but I soon realized that Félix was really worried. My idiot ex-husband had managed to terrorize him by predicting disaster if he didn’t get “a good eight hours of sleep.”

“But what will happen if I sleep less? Or more?”

Although I tried to soothe him, his anxiety kept him focused on that quota of hours.

“You see, it’s eleven now, Mummy, and the au pair’s going to come wake me up at eight, so if I don’t fall asleep in an hour, I won’t get enough …”

It was hard to stop his looping. And my growing ill temper wasn’t helping my attempts to calm Félix down. What infuriated me wasn’t that his father would want

some time to himself in the evening to be with his new companion, which was only reasonable, but that he would as usual formulate his needs and desires in the guise of an educational principle. Why would he upset a child on vacation like that? He should have told our son, ‘I need to be on my own now, so why don’t you hang out in your room, do some reading or play until you get tired.’ Félix would already be asleep instead of phoning me—and developing a sleep problem it would probably take me at least six months to get rid of! In the end, I comforted him as best I could, at least I hoped so, since I couldn’t do more over the phone.