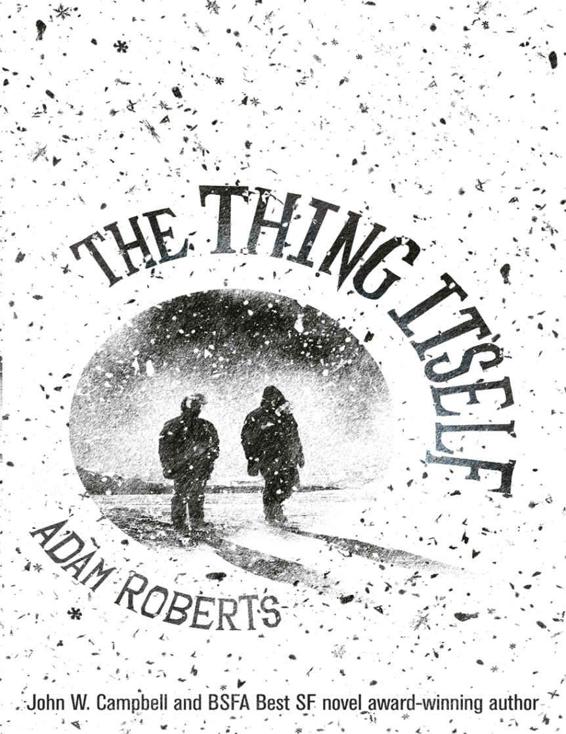

The Thing Itself

Authors: Adam Roberts

GOLLANCZ

LONDON

CONTENTS

8. The Fansoc for Catching Oldfashioned Diseases [

Causality

]

10. The Last Three Days of the Time War [

Possibility and Impossibility

]

Syncretism refers to that characteristic of child thought which tends to juxtapose logically unrelated pieces of information when the child is asked for causal explanations. A simple example would be: ‘Why does the sun not fall down?’ ‘Because it is hot. The sun stops there.’ ‘How?’ ‘Because it is yellow.’

G. H. Bantock

Thing and Sick

Unity

The beginning was the letter.

Roy would probably say the whole thing began when he solved the Fermi Paradox, when he achieved (his word)

clarity

. Not clarity, I think: but sick. Sick in the head. He probably wouldn’t disagree. Not any more. Not with so much professional psychiatric opinion having been brought to bear on the matter. He concedes as much to me, in the many communications he has addressed to me from his asylum. He sends various manifestos and communications to the papers too, I understand. In all of them he claims to have finally solved the Fermi Paradox. If he has, then I don’t expect my nightmares to diminish any time soon.

I do have bad dreams, yes. Visceral nightmares. I wake sweating and weeping. If Roy is wrong, then perhaps they’ll diminish with time.

But really it began with the letter.

I was in Antarctica with Roy Curtius, the two of us hundreds of miles inland, far away from the nearest civilisation. It was 1986, and one (weeks-long) evening and one (months-long) south polar night. Our job was to process the raw astronomical data coming in from Proxima and Alpha Centauri. Which is to say: our job was to look for alien life. There had been certain peculiarities in the radioastronomical flow from that portion of the sky, and we were looking into it. Whilst we were out there we were given some other scientific tasks to be keeping ourselves busy, but it was the SETI task that was the main event. We maintained the equipment, and sifted the data, passing most of it on for more detailed analysis back in the UK. Since in what follows I am going to say a number of disobliging things about him, I’ll concede right here that Roy was some kind of programming genius – this, remember, back in the late 80s, when ‘computing’ was quite the new thing.

The base was situated as far as possible from light pollution and radio pollution. There was nowhere on the planet further away than where we were.

We did the best we could, with 1980s-grade data processing and a kit-built radio dish flown out to the location in a packing crate, and assembled as best two men could assemble anything when it was too cold for us to take off our gloves.

‘The simplest solution to the Fermi thing,’ I said once, ‘would be simply to pick up alien chatter on our clever machines. Where are the aliens?

Here

they are.’

‘Don’t hold your breath,’ he said.

We spent some hours every day on the project. The rest of the time we ate, drank, lay about and killed time. We had a VHS player, and copies of

Beverly Hills Cop

,

Ghostbusters

,

The NeverEnding Story

and

The Karate Kid

. We played cards. We read books. I was working my way through Frank Herbert’s

Dune

trilogy. Roy was reading Immanuel Kant. That fact, right there, tells you all you need to know about the two of us. ‘I figured eight months’ isolation was the perfect time really to get to grips with the

Kritik der reinen Vernunft

,’ he would say. ‘Of course,’ he would add, with a little self-deprecating snigger, ‘I’m not reading it in the original German. My German is good – but not

that

good.’ He used to leave the book lying around: Kant’s

Critique of Pure Reason,

transl. Meiklejohn. It had a red cover. Pretentious fool.

‘We put too much trust in modern technology,’ he said one day. ‘The solution to the Fermi Paradox? It’s all in here.’ And he would stroke the cover of the

Critique

, as if it were his white cat and he Ernst Stavro Blofeld.

‘Whatever, dude,’ I told him.

Once a week a plane dropped off our supplies. Sometimes the pilot, Diamondo, would land his crate on the ice-runway, maybe even get out to stretch his legs and chat to us. I’ve no idea why he was called ‘Diamondo’, or what his real name was. He was Peruvian, I believe. More often, if the weather was bad, or if D. was in a hurry, he would swoop low and drop our supplies, leaving us to fight through the burly snowstorm and drag the package in. The contents would include necessaries, scientific equipment, copies of relevant journals – paper copies, it was back then, of course – and so on. The drops also contained correspondence. For me that meant: letters from family, friends and above all from my girlfriend Lezlie.

Two weeks before all this started I had written to Lezlie, asking her for a paperback copy of

Children of Dune

. I told her, in what I hope was a witty manner, that I had been disappointed by the slimness of

Dune Messiah

. I need the big books, I had said, to fill up the time, the long aching time, the (I think I used the phrase) terrible absence-of-Lezlie-thighs-and-tits time that characterised life in the Antarctic. I mention this because, in the weeks that followed, I found myself going back over my letter to her – my memory of it, I mean; I didn’t keep a copy – trying to work out if I had perhaps offended her with a careless choice of words. If she might, for whatever reason, have decided not to write to me this week in protest at my vulgarity, or sexism. Or to register her disapproval by not paying postage to send a fat paperback edition of

Dune III

to the bottom of the world. Or maybe she

had

written.

You’ll see what I mean in a moment.

Roy never got letters. I always got some: some weeks as many as half a dozen. He: none. ‘Don’t you have a girlfriend?’ I asked him, once. ‘Or any friends?’

‘Philosophy is my friend,’ he replied, looking smugly over the top of his copy of the

Critique of Pure Reason

. ‘The solution to the Fermi Paradox is the friend I have yet to meet. Between them, they are all the company I desire.’

‘If you say so, mate,’ I replied, thinking inwardly

weirdo!

and

loser

and

billy-no-mates

and other such things. I didn’t say any of that aloud, of course. And each week it would go on: we’d unpack the delivery parcel, and from amongst all the other necessaries and equipment I’d pull out a rubberband-clenched stash of letters, all of which would be for me and none of which were ever for Roy. And he would smile his smarmy smile and look aloof; or sometimes he would peer in a half-hope, as if thinking that maybe this week would be different. Once or twice I saw him

writing

a letter, with his authentic Waverley fountain pen, shielding his page with his arm when he thought I wanted to nosy into his private affairs – as if I had the slightest interest in fan mail to Professor Huffington Puffington of the University of Kant Studies.

He used to do a number of bonkers things, Roy: like drawing piano keys on to his left arm, spending ages shading the black ones, and then practising – or, for all I know, only pretending to practise – the right-hand part of Beethoven sonatas on it. ‘I requested an actual piano,’ he told me. ‘They said no.’ He used to do vocal exercises in the shower, really loud. He kept samples of his snot, testing (he said) whether his nasal mucus was affected by the south polar conditions. Once he inserted a radiognomon relay spike (not unlike a knitting needle) into the corner of his eye, and squeezed the ball to see what effects it had in his vision ‘because Newton did it’. He learned a new line of the

Aeneid

every evening – in Latin, mark you – by reciting it over and over. Amazingly annoying, this last weird hobby, because it was so particularly and obviously pointless. I daresay that’s why he did it.

I tended to read all the regular things: SF novels, magazines, even four-day-old newspapers (if the drop parcel happened to contain any), checking the football scores and doing the crosswords. And weekly I would pull out my fistful of letters, and settle down on the common room sofa to read them and write my replies, whilst Roy furrowed his brow and worked laboriously through another paragraph of his Kant.

One week he said, ‘I’d like a letter.’

‘Get yourself a pen pal,’ I suggested.

We had just been outside, where the swarming snow was as thick as a continuous shower of wood chips and the wind bit through the three layers I wore. We were both back inside now, pulling off icicle-bearded gloves and scarves and stamping our boots. The drop package was on the floor between us, dripping. We had yet to open it.

‘Can I have one of yours?’ he asked.

‘Tell you what,’ I said. I was in a good mood, for some reason. ‘I’ll sell you one. Sell you one of my letters.’

‘How much?’ he asked.

‘Tenner,’ I said. Ten pounds was (I hate to sound like an old codger, but it’s the truth) a lot of money back then.

‘Deal,’ he said, without hesitation. He untied his boots, hopped out of them like Puck and sprinted away. When he came back he was holding a genuine ten-pound note. ‘I choose, though,’ he said, snatching the thing away as I reached for it.

‘Whatever, man.’ I laughed. ‘Be my guest.’

He gave me the money. Then, he dragged the parcel, now dripping melted snow, through to the common room and opened it. He rummaged around and brought out the rubberbanded letters: four of them.

‘Are you sure none of them aren’t addressed to you?’ I said, settling myself on the sofa and examining my banknote with pride. ‘Maybe you don’t need to buy one of my letters – maybe you got one of your own?’

He shook his head, looked quickly through the four envelopes on offer, selected one and handed me the remainder of the parcel. ‘No.’

‘Pleasure doing business with you,’ I told him. Off he went to his bedroom to read the letter he had bought.

I thought nothing more about it. The three letters were from: my mum, a guy in Leicester with whom I was playing a tediously drawn-out game of postal chess, and the manager of my local branch of Lloyd’s Bank in Reading, writing to inform me that my account was in credit. Since Antarctica was hardly thronged with opportunities for me to spend money, and since my researcher’s stipend was still going in monthly, this was unnecessary. I’m guessing it was by way of a publicity exercise. It’s not that I was famous, of course; even famous-for-Reading. But it doubtless looked good on some report somewhere:

we look after our customers, even when they’re at the bottom of the world

! I made myself a coffee. Then I spent an hour at a computer terminal, checking data. When Roy came back through he looked smug, but I didn’t begrudge him that. After all, I had made ten pounds – and ten pounds is ten pounds.

For the rest of the day we worked, and then I fixed up some pasta and Bolognese sauce in the little kitchen. As we ate I asked him: ‘So who was the letter from?’

‘What do you mean?’ Suspicious voice.

‘The letter you bought from me. Who was it from? Was it Lezlie?’

A self-satisfied grin. ‘No comment,’ he smirked.

‘Say what?’

‘It’s my letter. I bought it. And I’m entitled to privacy.’

‘Suit yourself,’ I said. ‘I was only asking.’ He was right, I suppose; he bought it, it was his. Still, his manner rubbed me up the wrong way. We ate in silence for a bit, but I’m afraid I couldn’t let it go. ‘I was only asking: who was it from? Is it Lezlie? I won’t pry into what she actually wrote.’ Even as I said this, I thought to myself:

Pry? How could I pry – the words were written to be read by me!

‘You know,’ I added, thinking to add pressure. ‘I

could

just write to her, ask her what she wrote. I could find out that way.’

‘No comment,’ he repeated, pulling his shoulders round as he sat. I took my bowl to the sink and washed it up, properly annoyed, but there was no point in saying anything else. Instead I went through and put

Romancing the Stone

on the telly, because I knew it was the VHS Roy hated the most. He smiled, and retreated to his room with his philosophy book.

The next morning I discovered to my chagrin that the business with the letter was still preying on my mind. I told myself: get over it. It was done. But some part of me refused to get over it. At breakfast Roy read another page of his Kant, and I saw that he was using the letter as a bookmark. At one point he put the book down and stood up to go to the loo, but then a sly expression crept over his usually ingenuous face, and he picked the book up and took it with him.

It had been a blizzardy few days and the dish needed checking over. Roy tried to wriggle out of this chore: ‘You’re more the hardware guy,’ he said, in a wheedling tone. ‘I’m more conceptual – the ideas and the phil-horse-o-phay.’

‘Don’t give me that crap. We’re both hands-on. Folk in Adelaide, and back in Britain, they’re the

actual

ideas people.’ I was cross. ‘Philosophy my arse.’ At any rate, he suited up, rolled his scarf around his lower face and snapped on his goggles, zipped up his overcoat. We both pulled out brooms and stumped through light snowfall to the dish. It took us half an hour to clear the structure of snow, and check its motors hadn’t frozen solid, and ensure its bearings were ice free. Our shadows flickered across the landscape like pennants in the wind.

The sun loitered near the horizon. A cricket ball frozen in flight.

That afternoon I did a stint testing the terminals. With the sun still up, it was a noisy picture; although it was possible to pick up this and that. At first I thought there was something, but when I looked at it I discovered it was radio chatter from a Spanish expedition on its way to the Vinson Massif. I found my mind wandering. Who was the letter from?