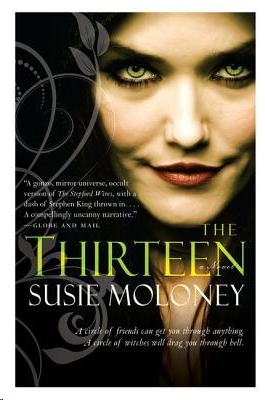

The Thirteen

Also by Susie Moloney

Bastion Falls

A Dry Spell

The Dwelling

PUBLISHED BY RANDOM HOUSE CANADA

Copyright © 2011 Susie Moloney

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2011 by Random House Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited.

Random House Canada and colophon are registered trademarks.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Cover design: Leah Springate

Cover images: (street scene) Munz/Getty Images; (clouds) © Mwp1969/

Dreamstime.com

; (cats) © Eric Isselée/

Dreamstime.com

Moloney, Susie

The thirteen / Susie Moloney.

eISBN: 978-0-307-36680-1

I. Title.

PS8576.04516T55 2011 C813.′54 C2010-907208-1

v3.1

For Michael, who still bewitches me

.

Contents

PROLOGUE

C

HICK WAS AN OLD-FASHIONED WOMAN

. In spite of the hour and circumstances, she was in full battle gear—that was what Bill used to call it. Matching bra and panty set, nothing fancy, but a

good

set; Spanx that were killing her like the old joke; stockings, a full slip, then her dress, her best dress, a dark navy Ralph Lauren with cap sleeves. Her Cartier watch, the pearls Bill gave her on their wedding day, matching earrings and her wedding ring.

She checked her reflection in the mirror, absently working the wedding ring around her finger, something she always did when she was lost in thought. But it was awkward with the bandage on her hand and she stopped. The burn throbbed constantly. She picked up the spray bottle and gave her hair a once-over of lacquer. This she smoothed down. The hair bounced lightly against her scalp with each soft pat, a feeling so pleasant she nearly began to weep again. Instead she leaned closer to the bathroom mirror, and under the cruel light she took a last look at herself. Not too bad. Not too bad for sixty. She was one of the older gals in her group, but she’d bet money no one outside their circle would know it.

—which made her think of the throbbing, painful burned surface of her palm and Bill saying

give me the keys, darling, don’t be silly

. But she wouldn’t give them to him. She squeezed the keys in her hand so he couldn’t see them. He held his confused smile, unsure of what else to say. Then the sudden, shocking burn in her palm forced her hand open and she dropped the keys, but Bill didn’t notice. Bill was under the influence, and it wasn’t drink or drugs, but Izzy and he didn’t notice her pain, the burned flesh on the key. It was just

thank you, dear, I’ll see you tonight

, but of course he didn’t see her that night at all—

Chick was still in the mirror; Bill was gone.

She left the bathroom light on and walked through her darkened house. The television, computer, radio—everything was off, and the curtains and blinds were drawn on every window. She used the bathroom light to navigate until she reached the living room, and then she went by memory.

Her shoes were still at the front door, where she’d taken them off after the funeral. They were pretty shoes, favourites. The insoles were cool on her feet when she slipped them on, but she grimaced putting her weight into them. She’d been in heels all day—since nine that morning, when Bradley and Thomas and their wives had arrived from the hotel to pick her up to go to the church. Of course they hadn’t wanted to leave her alone, but she’d insisted, telling them that Audra—whom they’d known all their lives—would be with her. But in fact she’d sent Audra away too.

Chick had only sons, no daughters. They would miss her a little bit, but then they would be fine.

Bradley was an EMT. Not quite a doctor, but Chick and Bill were proud of him. He’d been very concerned about her hand. She hadn’t let him see it, afraid of the questions he would ask about the key-shaped scar. She’d snapped at him when he’d persisted, and she was sorry now. There had been a time when she would have cut out her own tongue rather than lash out at one of her boys, but it changed when they left home. Bill had filled that void in her heart in a way he hadn’t been able to when her sons were little.

Until the previous Sunday, that is, and his horrible crash. What had he seen right before he died? Did he see something in the road? The car had swerved violently off the highway into a tree. He’d been speeding.

Was it an animal in the road? The two-legged kind?

Chick ran a hand up the back of her leg to her knee, smoothing her stockings. Her legs were still good. She didn’t need Bill to tell her that, but he always had. Vanity. One of the seven deadly sins. What were the others?

Gluttony, anger, lust, avarice, envy, forsaking all gods except me

—Maybe that one was a Commandment. She couldn’t think.

She wobbled a little, feeling the first effects of the four Valiums she’d swallowed with a little supper, just enough to keep the woozies at bay, as the website had said.

The shoes were very expensive, the leather soft as butter and a rich navy, bought to match her dress. Oh, so beautiful. Shoes were one of life’s great pleasures. There were really so many: shoes, lunch out, slow and quiet lovemaking in the morning, a glass of wine when you were cooking, fresh laundry, a laugh—

A person didn’t need much. Not really. She wished she’d known that sooner.

She made her way to their bedroom, leaving the bathroom light on to guide her.

The bed was made, the coverlet pulled over the pillows. The whole house was clean and tidy, the dishes done and put away, laundry basket empty. She’d watered the plants and washed the kitchen floor, dusted her Hummels and paid what bills there were. She’d done everything she could in the first days after Bill was killed, trying to fill the hours, trying not to be hysterical.

The smell was very strong in the bedroom, unbearable, and there was a bad moment when she felt the smell in her belly and thought the pills she’d painstakingly taken were going to come up. She kept them down by breathing shallowly. She got used to it.

Chick crawled up the bed from the foot until she reached the pillows and allowed herself to drop. She rolled over onto her back, stared up at a black ceiling in a black room and contemplated her exhaustion.

Bill used to like to be tired. It was a silly thing to say, but he used to tell her

there’s nothing like sleeping when you’re tired, Chick, except drinking when you’re thirsty

. The Valiums washed over her with every beat of her heart, thrumming in her ears. It was a pleasant feeling. Downers, the kids called them. It felt … smooth.

(but even under the smooth, sweet, soft feel of the pills, her hand still throbbed badly where it was raw and)

Chick felt around under the pillow until she found what she was looking for. Then she reached for the framed photo on the bedside table, of Bill and her on their trip to Mexico two years earlier. She’d debated between this and their wedding photo before settling on the more recent picture, because she realized that she loved him so much more now than when they first were married.

In fact, when they had first been married, she had found him ridiculous too often to admit. He never seemed to do anything right and she despaired of their ever getting anywhere in life. He chewed with his mouth open. Thought he was funnier than he really was.

But their marriage had experienced renaissance after renaissance.

Bill oh god Bill oh god

I am so sorry

The Valium cast a fog over everything, making her movements sluggish and clumsy. Still she waited a bit, until she was sure that all she ever wanted to do for the rest of her life was

sleep

With her right hand she flipped open the top of the Zippo and, after a weak try, got it lit. She dropped the lighter to the floor of her gas-soaked bedroom and closed her eyes, uninterested in the flames that popped and exploded, focusing instead on the drugged amber glow inside her head. Because she was so afraid of what she might see in the moments before her body died, so afraid of what reckoning there might be—

She did not move from the bed. Not even when the flames swept up from the floor and began their climb over her

surrender your

flesh.

Primarily she felt an exhausted relief.

I give my flesh to you to do with as you please as I please you Father

As the room filled with smoke, the air harsh, her breathing became choked. The hairspray caught and flamed, melting her hair to her head as the fabric of her dress blistered against her flesh, the skin bubbling and puckering in the heat, her scarred hand unfurled like the petals of a flower. Her last breath felt like a sigh.

sorry so sorry my love my Bill

Her last thought was,

That house on the edge of town should burn burn burn—

She burned, and the fire sounded like screams.

It was a bad night in Haven Woods.

Not long after the first fire trucks arrived at the home of Chick and Bill Henderson (Bill recently deceased), there was more trouble just a couple of blocks over.

Audra Wittmore had been making herself a cup of tea, something soothing, something kind after the unkind day she’d spent with Chick, the two of them in a tight protective (fearful) little hive.

Chick had cried a lot. Not so much when there were people around, but when they were alone. Over Bill, poor old Bill.

It had nearly broken Audra’s heart, her good friend so full of self-loathing and remorse. So very broken-hearted.

Audra too had been inconsolable in the first days after Walter died. Had wept. She’d leaned heavily on her own best friend, Isadora Riley—Izzy. Izzy was no longer such a friend. So much could change in ten years.

Walter had died in a crash too. A terrible coincidence.

wasn’t it just

Izzy had been at the funeral that afternoon, of course she had. Everyone in the neighbourhood had been there. She’d sat close to the front, with her daughter Marla and the two grandchildren.

Audra had stayed close to Chick, watching always for where Izzy was, keeping the two apart. Except for the receiving line, of course; there was nothing one could do about that. But still she’d stood beside Chick, letting Chick lean into her, holding Chick’s arm, the good arm, with the unbandaged hand.

Terrible thing, that burn. Audra had seen it, had bandaged it herself. It was a good two inches long and at least an inch across, the whole thing a sort of T shape.

But it wasn’t a T, it was a key. Seared into the flesh of her palm you could make out the letters F-O-R-D. Chick’s son the almost-a-doctor had bugged her and bugged her to show it to him. How could she, poor thing?

It didn’t bear thinking about. You just couldn’t go down that road, or you would never sleep again.

She poured water slowly over the leaves and stared as the brew turned to a rich amber.

Audra’s own dear husband had been dead now a very, very long time. She was still lonely for him. At least, she made herself believe that she was lonely for him and not just for anyone at all. Lonely for her family really. Her daughter. Her

granddaughter

, such a pretty little thing, just like her mother had been at that age. She never saw her. Rarely.

Dear Paula.

(dear Paula may you stay away far far away from Haven Woods)

Very briefly she’d had a man-friend. A neighbour, divorced, whose wife had moved away and left him behind in Haven Woods. Gabe, across the lane. He gardened, and when Audra took her dog, Tex, for a walk, she often found herself passing his yard, hoping he was in the garden. They talked about tomatoes and growing seasons and apple pie made from apples from their own trees. They both had real nice ones.

That’s just how it goes, no matter how old you are or where you live. It starts with

oh I was just passing by

and then you get a cutting of something and then it grows a little and the giver stops by to see it and then it’s coffee on the deck and pretty soon someone’s baking something for someone. And then—if you live in Haven Woods—sooner or later Izzy Riley comes over and says with a certain curl of lip:

I see you’ve made a friend

.

It had gotten as far as apple-tree pie when Izzy came around and she and Audra had their chat about the state of the neighbourhood and how distracting things can be for a woman of a certain age, and was

another

man really a smart thing to do?

Eventually poor Gabe—who was funny and kind and good with the earth—moved away himself. And that was that.

Audra picked up her tea, carried it to the table in the kitchen and sat down. She blew at the steam that still wafted from the cup, and she was just thinking that maybe it hadn’t been a good idea for her to leave Chick alone, even though Chick had insisted, begged even

(and Audra had just wanted to go home)

when the first sirens began, far enough away that Audra barely heard them. She had taken a good long sip of the tea before they became so loud she realized they were coming to the neighbourhood. She stood and headed for the front window of the house, where she had a pretty good view.

As she walked, her knees grew sick-weak and her joints suddenly seized up and her eyesight blurred and her heart raced and she was quite sure she was

having a heart attack

and she dropped to the floor like a stone, the teacup flying from her hand, hitting the floor and breaking, the tea splattering against the wall and the curtains over the front window, spreading in a damp smear like blood.

Audra was staring at the ceiling and she was utterly unable to move, but she could see the glow of the fire outside the window even as she heard the spray of water from the huge trucks and the flashing red-white of the emergency lights.

Then Izzy was standing over her, saying

not feeling well?

And of course it wasn’t a heart attack.

It was a bad night in Haven Woods.