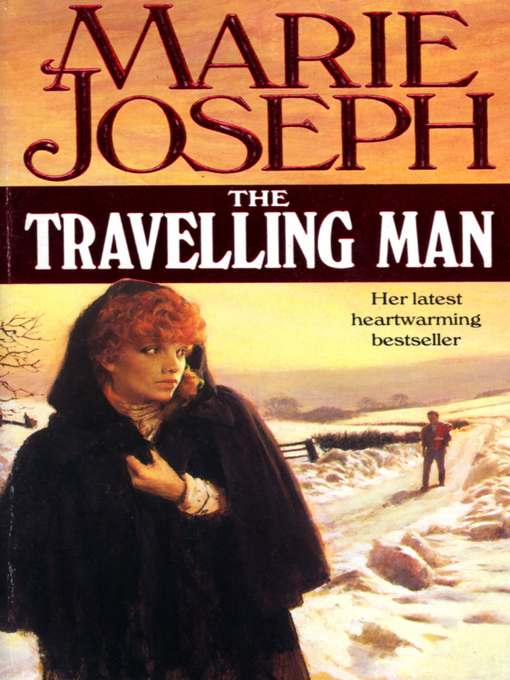

The Travelling Man

| The Travelling Man | |

| Marie Joseph | |

| Random House (2012) | |

| Tags: | Fiction |

Synopsis

When the exotic stranger walked into the loveless Clancy household, he brought a gift to innocent seventeen-year-old Annie that neither her five brothers, nor her brutal father, had ever given her ... tenderness. And, like many before her, Annie pays the price for its sweetness. An outcast from her home and adrift in a harsh world, it would take a long time for Annie to trust a man again ... Inspired by Marie Joseph's storytelling magic, and set in the wild and sweeping Lancashire countryside, The Travelling Man is another of her gripping, page-turning sagas.

About the Author

Marie Joseph was born in Lancashire and was educated at Blackburn High School for Girls. Before her marriage she was in the Civil Service. She now lives in Middlesex with her husband, a retired chartered engineer, and they have two married daughters and eight grandchildren.

Marie Joseph began her writing career as a short-story writer and she now uses her Northern background to enrich her bestselling novels. Down-to-earth characters bring a vivid authenticity to her stories, which are written with both humour and poignancy.

Her novel:

A Better World Than This

won the 1987 Romantic Novelist’s Association Major Award.

ALSO BY MARIE JOSEPH

RING A-ROSES

MAGGIE CRAIG

A LEAF IN THE WIND

EMMA SPARROW

GEMINI GIRLS

THE LISTENING SILENCE

LISA LOGAN

THE CLOGGER’S CHILD

POLLY PILGRIM

A BETTER WORLD THAN THIS

A WORLD APART

PASSING STRANGERS

Marie Joseph

For Ali

…

DOWN IN LONDON

, Queen Victoria’s coffin, borne on a gun carriage and covered by the royal standard, was taken to the mausoleum at Frogmore. Londoners wept openly in the streets, and up in the industrial heart of Lancashire the Old Trouper, as the working man called her, was talked about with pride. For wasn’t she one of them in the way she had carried on fighting, signing her papers right up to the week before she died? They doubted if they’d ever see the likes of her again.

It was the end of an era.

It was 1901.

At the back end of that year Jack Clancy told his daughter Annie about the lodger.

‘A lodger?

Here

?’ Her eyes almost popped out of their sockets. ‘Where is he going to sleep then? You’re never going to let him sleep in your room, are you, our Dad?’

She could tell her father was in one of his blustering moods. He always blustered when he was in the wrong, especially when there wasn’t the drink in him. Annie watched him warily from one side of the square table in the front living-room of the terraced house. It was always as well to have the width of the table between them when her father was in one of his rages. Often the best thing to do was to scarper out the back way and hide up for a bit till he calmed down.

But first she’d have a go at reasoning with him.

‘You know full well there’s only the two rooms upstairs – you in one, the five lads in the other – and me down here in the back scullery.’ She folded her arms across

a

sacking apron. ‘There’s no room in this house for a lodger, unless he’s going to sleep on the clothes-line!’

For once Jack Clancy was being on his dignity. If he could have stood up straight fixing his daughter with a look, he would have done so. But after working underground for more than thirty years, crawling on his knees for a lot of the time, he would never straighten up properly again. His face was a map of criss-crossed blue scars, and the mark of an old injury stood out on his forehead like a bulging vein.

The truth he would never admit to was that he

regretted

offering a stranger a place to doss down in the two-up, two-down house, though he would rather die than say so. He knew it had been the ale talking, but he wasn’t going to admit that either.

‘He can sleep on that.’ He jerked his head at the rag rug by the fire. ‘Laurie Yates has been a sailor, so he won’t be expecting to sleep in a four-poster with sheets and blankets. Anyroad, like I said, he’s coming, and when he gets taken on at the pit and starts bringing money in …’

‘You mean he hasn’t even got a

job

, our Dad! No job an’ no money? You mean I’ve got to feed him as well as all the others? Do you know what there is to last us till Friday? A measly rabbit, half a bag of oatmeal, some spuds sprouting their eyes out, and a piece of scrag end as thin as a sheet of tissue paper.’

She was so mad she could feel tears warming the back of her eyes, but she wasn’t going to let them fall. Annie Clancy was no crier. ‘Crying never got the baby a new bonnet,’ she always told herself when things got too bad and

somehow

, since her mother’s death four years ago, she had managed, even on the money her father grudgingly tipped over to her. And now her eldest brother Georgie was twelve and working, things were beginning to look up.

Annie was a good manager and she knew it. She could make a stew that stuck to your ribs out of a few bones,

a

handful of vegetables and a good scattering of barley. She knew how to simmer an ox-tail in the fire oven till the meat dropped from the bone as tender as butter, and she could roll oatcakes so thin you could see the graining on the table through them.

Oh yes, she’d managed all right, even though there were times when she’d gone to bed so hungry she could have gnawed the table leg. She had seen to it that the boys never went to school barefoot; she had coped with the dirt her father and Georgie brought back from the pit.

She wore a dark patterned cotton blouse that day, a long brown skirt, and two aprons, one of shiny black fent and the top one of sacking. Her hair was tucked up into a man’s flat cap, and her hands and wrists were the reddy-brown of potted meat. She was as thin as a picked chicken and her eyes, an unusually dark blue, were the eyes of someone who, while hoping for the best, more often got the worst.

‘There’s six of you!’ she was shouting now. ‘All lads. And now you tell me you’re fetching another one to live here!’

Frustration and fury welled up in her throat, making her feel sick. She could hear herself yelling, she knew she was sounding as common as dirt and that her mother would have been ashamed of her; accepted she was making as much noise as Mrs Greenhalgh at the bottom of the street did when she was having a go at her daughter-in-law. Yet Annie was

glad

the door was open. She hoped everybody in the street was listening. Let them all crowd round the door and hear what she had to say, because she hadn’t finished yet, not by a long chalk she hadn’t.

‘No wonder me mother never got over the last one of us being a boy. She was sick and tired of listening to rough talk; sick of cooking stews that got gulped down in a minute, and tired out of having to do everything herself, without anybody stretching out a finger to help

her

. You even let her fetch the coal in from the back when she was expecting …’

Annie knew she was going too far, but nothing could stop her now. In a strange way she was glorying in the sound of her raised voice, exulting in the fact that she was daring to speak her mind.

‘One more mucky face, one more pair of clogs under the table! You must think I’m doo-lally!’

Totally beside herself, no longer in control of the words spilling from her mouth, Annie stared at the thick-set man across the table, infuriating her by remaining uncharacteristically silent. She lowered her voice to a fierce whisper:

‘An’ while we’re getting a few things straight, it wasn’t the consumption that took me mother off neither. It was malnutrition, our Dad.

Starvation

!’

Jack Clancy took a menacing step forward, leaning on the table edge, gripping it with his hands. He could feel his throat swelling and hear blood pounding in his head. He’d vowed after the last time when they’d had to bring the doctor to her, that he would never hit Annie again, no matter how much she provoked him. But what she’d just said … Good God Almighty, he’d be less than a man to let her get away with that. Some of the things she came out with would make even the Angel Gabriel spit.

When he hit her she rocked back, clutching at the chair to save herself from falling. The stinging pain in her left ear made her eyes water, so that all she wanted to do was to rock backwards and forwards, moaning the pain away. But the white hot anger inside sustained her.

As her father reached the door she was there, shouting after him as he walked away from her, hunch-shouldered down the cobbled street. Just like Mrs Greenhalgh at the bottom house, Annie stuck her chin out, put her hands on her hips and screamed at the top of her voice: ‘If that bloomin’ lodger comes in at our front door, then it’s me out the back, our Dad!’ She stepped out on to the uneven flagstones and shook

both

fists in the air. ‘I’m telling you! So think on. Think on!’

Jack didn’t bother to turn round. He was used to his daughter’s ways. He could afford to bide his time, knowing she would calm down as quickly as she’d flared up. She was one on her own all right – had been from the day she was born. He turned the corner, hobnailed boots ringing on the flags. Annie was as different from the boys as chalk from cheese. Where they sulked or merely shrugged their shoulders, Annie yelled. Old Doctor Bradley had called her the strongest lad in the family, and by the left, he was right. It was as if a fire burned inside her, giving her the strength of a man. She could hump the coal in from the yard, or turn a flock mattress without catching her breath. Yet she wasn’t the size of two pennorth of copper. But he’d best her. He’d show her who was boss. He turned up his jacket collar against the wind which felt as if it was coming straight from Siberia.

Jack Clancy’s father had brought his son over from Ireland to work on the farms around Ormskirk, but the minute he could get away Jack was down the mines, working alongside men who talked his language, doing a bit of wrestling in his spare time, playing pitch and toss on Sunday mornings instead of going to nine o’clock Mass. He had ordered the priest from his house on more than one occasion, and had managed to convince himself that all church-goers were hypocrites. His wife had been a Methodist. In Jack’s opinion the worst hypocrites of all.

Instead of going back inside, Annie went two doors down to the house where Grandma Morris lay in bed in the front room; she had been a bedridden invalid for as long as anyone in the street could remember. All Annie knew was that the old woman had bad legs, but she was always working at something with her strong arms and hands – knitting, sewing, peeling potatoes, earning her keep as

she

often said. When Annie lifted the sneck on the front door and walked in, Grandma Morris put down the sheet she was hemming and took off the steel-rimmed glasses she wore on the very tip of her nose.

Annie came straight to the point – there was no other way. Grandma Morris missed nothing that went on in the street, though she kept what she saw and heard to herself, never skitted about it or passed on a confidence. Nobody knew how she’d come to be called Grandma by everybody. There were certainly no grandchildren of her own, as her only daughter Edith was a spinster teacher of fifty summers who played the harmonium at Sunday School and said she had need of no other friend in her life but Jesus.