The Triumph of Seeds (11 page)

Read The Triumph of Seeds Online

Authors: Thor Hanson

Tags: #Nature, #Plants, #General, #Gardening, #Reference, #Natural Resources

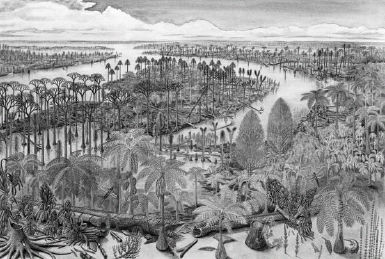

I snapped a picture and then scrabbled up the hillside to join in the hunt. The rock face above the coal broke apart easily, and soon I was finding my own fossils—a few ferns and horsetails, but mostly an unrecognizable jumble of leaves, stems, and spiky twigs. Around me, the paleontologists worked and talked excitedly. Where my eyes saw only dust and confusion, I knew theirs were reconstructing an ancient world. I tried to picture the calamites and seed ferns as living plants and my mind immediately turned to textbook images of the

Carboniferous: a steamy swamp festooned with huge, mossy-topped trees like something from a Dr. Seuss book, and populated by newt-like amphibians as large as horses. It was an era long before dinosaurs, let alone more familiar creatures like mammals and birds. There would have been dragonflies and a few spiders, but no ants, beetles, bumblebees, or flies. While a swamp without mosquitoes sounds appealing, the forest would have seemed strange for all that it lacked. Then I reminded myself that, if Bill was right, the landscapes of the Carboniferous might actually have looked a lot more like home.

“It should be called the Coniferous!” he burst out during one of our conversations. “The evidence now really suggests that coal was a minor element.” Once Bill’s team began questioning conventional wisdom, they started seeing compelling signs of a hidden flora, a community of conifers and other seed plants that lived uphill from

the swamps. Though it probably covered all but the wettest places, this forest left almost no trace of itself behind—just the occasional leaves and branches that washed down from above. “There’s a problem with terrestrial plants,” he explained. “They don’t preserve well in place.” Making good fossils requires fine-grained sediments and water, common ingredients in the swamps where spore plants ruled, but rare everywhere else. So while giant horsetails and club mosses may dominate the Carboniferous fossil record, that doesn’t mean they dominated the Carboniferous.

F

IGURE

4.2. This classic view of a Carboniferous coal forest shows a swampy world dominated by ferns, horsetails, and other spore plants. Evidence now suggests that only a small part of the world was wet and hot, and that conifers and other seed plants dominated large swathes of upland habitats. Anonymous (

Our Native Ferns and Their Allies

, 1894). I

LLUSTRATION

BY

A

LICE

P

RICKETT, TECHNICAL ADVISER

T

OM

P

HILLIPS

, U

NIVERSITY OF

I

LLINOIS

, U

RBANA

-C

HAMPAIGN

.

New climate research makes the case even stronger, refuting the stereotypical image of the Carboniferous as a monotonous era of hot, humid weather. Instead, it repeatedly swung from sultry periods to ice ages and back again. Coal accumulated only at the wettest times, and the wet times were interrupted by long dry spells when seed plants would have covered even more of the landscape. In this view, spore plants fall from a position of prominence to that of a relative anomaly—minor players in both geography and duration. But because they grew in swamps, they left behind an overwhelming, disproportionate, and ultimately misleading number of fossils—what paleontologists call a

preservation bias

.

“Where’s Thor?” I heard someone call out. “The Czechs found some seeds!” I’d only been with the group for half a day, but everyone already seemed to know what I was working on, and just showing up had earned me a place in the first-name club. The trip leader walked over and handed me a small block of stone speckled with black marks. Through my hand lens they looked like watermelon pips ringed by thin membranes. I asked Bill what they were, but he only shrugged: “You’re best off just calling them winged seeds.” Fossil seeds rarely had names, he explained, because they were almost never found with the plants that produced them. Later that day I saw what he meant as I pored over trays of fossils at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science in Albuquerque. There were scores of seeds, collected over decades, with labels like: “Seed?” “Ovule?” “Partial Cone?” or “Unknown Fruiting Body.” In

one famous case, the “seeds” of a well-known ancient plant turned out to be fossilized pieces of a millipede.

“Man, I wish someone would work on paleo seeds,” a curator told me later at the conference social hour (wine, beer, and heavy hors d’oeuvres served up in a warehouse full of fossils). “We’ve got one that looks like a mango pit, but with a big keel like a sailboat, and it’s covered with hairs. What kind of plant made that?!?”

I agreed wholeheartedly. Studying ancient seeds would open a window on Bill’s hidden plant communities. After all, for every unknown seed lying in a museum somewhere, there must have been an unknown seed plant uphill from a swamp, raining its progeny down into the muck below. What’s more, those seeds dated to a time when all their critical traits were just evolving—nourishment, dispersal, dormancy, defense. For seed biologists, the most exciting aspect of Bill’s theory is what it does for the story of seed evolution.

The traditional view put seeds on the map at the dawn of the Carboniferous, or perhaps a bit earlier. Then, for more than 75 million years, nothing much happened. One had to accept that seed plants, with all their advantages, could only eke out a small living in the coal swamps until the climate changed in the Permian. This version of events left two glaring questions unresolved. First of all, if seeds represented such a substantial and successful evolutionary change, then why did they remain insignificant for so long? Second, if seed traits like nourishment, protection, and dormancy were so well suited to dry and seasonal climates, then how did they evolve in a swamp? Relocating seed evolution to the uplands makes these problems disappear. Suddenly, the seed strategy becomes a logical adaptation that allowed the early innovators to colonize huge swathes of unoccupied habitat. Bill and a growing number of his colleagues now think that seed plants dominated the Carboniferous, spreading and multiplying into diverse forms that the fossil record only hints at. The “rapid” rise of seed plants in the Permian finally makes sense. When the climate dried out for good, seed plants took over quickly for a very good reason: they were already there.

“I really put the pieces of this together over a long career,” Bill told me, making a point of crediting his many collaborators. But overturning long-held beliefs in science never comes without controversy. “There are colleagues of mine who violently disagree with me,” he admitted. “But I just try to be kind and keep smiling, keep saying it. My thesis adviser always told me, ‘Don’t argue; just keep working.’” Bill seems to have taken that advice to heart. After the field trip, the conference moved indoors, where people gave presentations on their research. Heated debates often erupted, but Bill always stayed out of them (and often did have a smile on his face). Later, however, I heard him restate his philosophy with a slightly different twist: “Never argue with a fool—an onlooker can’t tell the difference.”

If any of Bill’s colleagues really do “violently disagree” with him, I didn’t meet them in Albuquerque. Everyone I spoke with at the conference endorsed the notion of a dynamic Carboniferous climate, where coal forests were an interesting but by no means dominant part of the landscape. An affable Brit named Howard Falcon-Lang proposed moving back the origin of conifers by tens of millions of years, strengthening the notion of rapid seed plant evolution in the uplands. There was a Canadian graduate student who said his adviser had instructed him to “get close to Bill, and learn everything I can.” But it was Stanislav Opluštil from Prague who put it best. He had once believed strongly in the traditional view, he told me, but now considered the matter settled. “Bill changed my mind.”

I left New Mexico with a completely revised mental image of the Carboniferous. The big newts and dragonflies remained, but now I pictured them against a backdrop that looked a lot more like home: a forest of conifers. Bill DiMichele’s work brings the story of seed evolution out of the swamp, putting it in a dry, upland context where a seed’s many adaptations for aridity make sense. But it’s still a long journey from spore to seed. To truly understand that leap, we must ask some indelicate questions about the private lives of plants.

W

hen spore plants have sex, they usually do it in dark, wet places, and quite often with themselves. A fern, for example, casts off thousands or even millions of spores every year, microscopic blips that float like earthy smoke from the edges and undersides of its leaves. Each spore consists of a single thick-walled cell with no additional protection or stored energy. It will only sprout if it lands on just the right patch of damp soil, and even then it does not grow into another fern as we know it. Instead, fern spores produce an entirely separate and unrecognizable plant, a tiny, heart-shaped nub of green smaller than a fingernail. It is this plant, the

gametophyte

, that has the equipment necessary for fern sex.

When gametophytes make eggs, they also send forth swimming sperm that can paddle their way through muddy water in the soil for an inch or two (two to five centimeters). Only if that journey unites the sperm with a nearby egg will fertilization take place and a new, familiar-looking fern sprout up. The details of this system vary, but all spore plants relegate sex to a separate generation, and all of them require water for their sperm to find an egg. Those traits work fine in wet weather, but they were problematic whenever the great swamps of the Carboniferous started to dry up. Reproduction became a challenge, and having two stages to their life cycle made it doubly hard to adjust to the changing climate.

“If spore plants wanted to make major adaptations,” Bill explained, “then both phases of their life cycle had to adapt to it. And that’s very difficult.” In other words, the tiny gametophyte not only looks different, it might also have very different requirements for soil, moisture, light, or other conditions. “I used to tell my students, ‘Imagine that your sperm or eggs grew up into little one-third versions of yourself, and then those little yous had to have sex to produce another you. And what if they looked different? What if they were totally independent and had no knowledge of your existence? What if you decided you wanted to live somewhere different? If they wouldn’t or couldn’t go there, then neither could you!’”

F

IGURE

4.3. Wallace’s spike moss (

Selaginella wallacei

). Like the common ancestor of all seed plants, this spike moss has taken the evolutionary leap of separating male and female spores. The males, precursors to pollen, are pictured on the upper right, emerging from their pouch like a smear of dust. The much larger female spores appear directly below. I

LLUSTRATION

© 2014

BY

S

UZANNE

O

LIVE

.

In some ways, it’s as if seeds evolved in response to the limitations of spores. Instead of banishing sex to the soil, they united parental genes on the mother plant, equipped that progeny with food, and dispersed it in a durable, protective case that could withstand the elements and sprout when conditions were right. Eventually, they even replaced the swimming sperm with pollen, eliminating the need for water. With so few ancient seed fossils to look at, experts still argue about the details of this transition. But everyone agrees that it was well underway

by the early Carboniferous. And while every step may not be preserved in stone, living examples survive in the modern descendants of spore plants that persist, and even thrive, all around us. I didn’t need to travel to a conference to see them—they grow right in my own backyard.

Every day, my short walk to the Raccoon Shack leads me past spore plants, from moss in the lawn to a patch of bracken fern that has survived years of mowing, weed-whacking, slash fires, and the depredations of our chickens. But the particular spore plant I wanted to see grew a few miles down the road, on a rocky bluff overlooking the sea where most visitors to our island gathered to watch for orca whales. On a clear January morning, I packed a sandwich and headed there to search for a somewhat smaller, but no less remarkable, species, Wallace’s spike moss.