The Trojan War (2 page)

Authors: Barry Strauss

The most important texts about the Trojan War are two long poems, called epics because they tell of the heroic deeds of men long gone. The

Iliad

is set near the end of the Trojan War, and it covers about two months of the conflict. The

Odyssey

relates the hero Odysseus's long, hard trip home from Troy; it adds only a few additional details about the Trojan War. Both of these texts are attributed to a poet named Homer.

Other poems about early Greece were also written down in Archaic Greece. Known as the “Epic Cycle,” six of these poems narrate the parts of the Trojan War missing from the

Iliad

and

Odyssey.

These poems are the

Cypria,

on the outbreak and first nine years of the war; the

Aethiopis,

which focuses on Troy's Ethiopian and Amazon allies; the

Little Iliad,

on the Trojan Horse; the

Iliupersis,

on the sack of Troy; the

Nostoi,

on the return of various Greek heroes, especially Agamemnon; and the

Telegony,

a continuation of the

Odyssey.

Unfortunately, only a few quotations from the Epic Cycle as well as brief summaries survive today. Many, many later writers in ancient times used these and other sources to comment on Homer.

Finally, there is ancient art, both painting and sculpture, which often illustrates details of the Trojan War, sometimes in invaluable ways for historians.

T

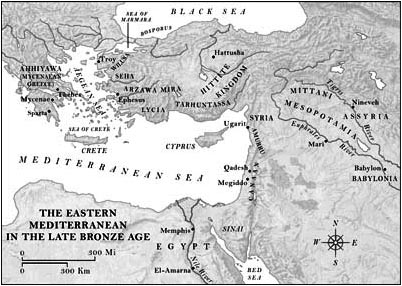

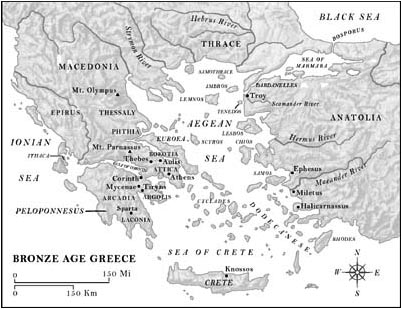

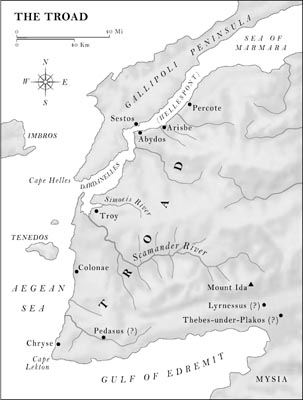

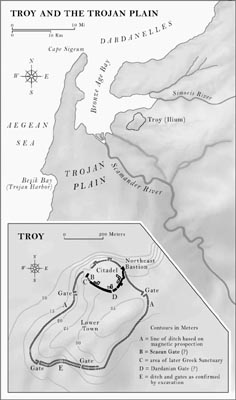

roy invites war. Its location, where Europe and Asia meet, made it rich and visible. At Troy, the steel-blue water of the Dardanelles Straits pours into the Aegean and opens the way to the Black Sea. Although the north wind often blocked ancient shipping there, Troy has a protected harbor, and so it beckoned to merchantsâand marauders. Walls, warriors, and blood were the city's lot.

People had already fought over Troy for two thousand years by the time Homer's Greeks are said to have attacked it. Over the centuries since then, armies have swept past Troy's ancient walls, from Alexander the Great to the Gallipoli Campaign of 1915.

And then there are the archaeologists. In 1871 Heinrich Schliemann amazed the world with the announcement that a mound near the entrance to the Dardanelles contained the ruins of Troy. Schliemann, who relied on preliminary work by Frank Calvert, was an inspired amateur, if also something of a fraud. But the trained archaeologists who have followed him by the hundreds in the 130 years since have put the excavations on a firm and scientific basis. And they all came to Troy because of the words of a Greek poet.

But are those words true? Granted that ancient Troy really existed, was it anything like the splendid city of Homer's description? Did it face an armada from Greece? Did the Trojan War really happen?

Spectacular new evidence makes it likely that the Trojan War indeed took place. New excavations since 1988 constitute little less than an archaeological revolution, proving that Homer was right about the city. Twenty years ago, it looked as though Troy was just a small citadel of only about half an acre. Now we know that Troy was, in fact, about seventy-five acres in size, a city of gold amid amber fields of wheat. Formerly, it seemed that by 1200

B.C.

Troy was a shabby place, well past its prime, but we know now that in 1200 the city was in its heyday.

Meanwhile, independent confirmation proves that Troy was a byword in the ancient Near East. This outside evidence comes not from Homer or any Greek source but from Hittite texts. In these documents, the city that Homer calls Troy or Ilion is referred to as Taruisa or Wilusaâand in the early form of the Greek language, “Ilion” was rendered as “Wilion.”

A generation ago scholars thought that the Trojans were Greeks, like the men who attacked them. But new evidence suggests otherwise. The recently discovered urban plan of Troy looks less like that of a Greek than of an Anatolian city. Troy's combination of citadel and lower town, its house and wall architecture, and its religious and burial practices are all typically Anatolian, as is the vast majority of its pottery. To be sure, Greek pottery and Greek speakers were also found at Troy, but neither predominated. New documents suggest that most Trojans spoke a language closely related to Hittite and that Troy was a Hittite ally. The enemy of Troy's ally was the Greeks.

The Greeks were the Vikings of the Bronze Age. They built some of history's first warships. Whether on large expeditions or smaller sorties, whether in the king's call-up or on freebooting forays, whether as formal soldiers and sailors or as traders who turned into raiders at a moment's notice, whether as mercenaries, ambassadors, or hereditary guest-friends, the Greeks fanned out across the Aegean and into the eastern and central Mediterranean, with one hand on the rudder and the other on the hilt of a sword. What the sight of a dragon's head on the stem post of a Viking ship was to an Anglo-Saxon, the sight of a bird's beak on the stem post of a Greek galley was to a Mediterranean islander or Anatolian mainlander. In the 1400s

B.C.

, the Greeks conquered Crete, the southwestern Aegean islands, and the city of Miletus on the Aegean coast of Anatolia, before driving eastward into Lycia and across the sea to Cyprus. In the 1300s they stirred up rebels against the Hittite overlords of western Anatolia. In the 1200s they began muscling their way into the islands of the northeastern Aegean, which presented a big threat to Troy. In the 1100s they joined the wave of marauders, known to us as the Sea Peoples, who descended first on Cyprus, then on the Levant and Egypt, and settled in what became the Philistine country.

The Trojan War, which probably dates to around 1200

B.C.

, is just a piece in a larger puzzle. But if the resulting picture builds on Homer, it differs quite a bit from the impression most readers get from his poems. And “impression” is the right word, because much of the conventional wisdom about the war, from Achilles' heel to Cassandra's warnings, is not in Homer at all.

Consider what Homer does say: He tells the story in two long poems, the

Iliad

or Story of Ilion (that is, Troy) and the

Odyssey

or Story of Odysseus. According to Homer, the Trojan War lasted ten years. The conflict pitted the wealthy city of Troy and its allies against a coalition of all Greece. It was the greatest war in history, involving at least 100,000 men in each army as well as 1,184 Greek ships. It featured heroic champions on both sides. It was so important that the Olympian gods played an active role. Troy was a magnificent city and impregnable fortress. The cause of the war was the seduction, by Prince Paris of Troy, of the beautiful Helen, queen of Sparta, as well as the loss of the treasure that they ran off with. The Greeks landed at Troy and demanded the return of Helen and the treasure to her husband, Sparta's King Menelaus. But the Trojans refused. In the nine years of warfare that followed, the Greeks ravaged and looted the Trojan countryside and surrounding islands, but they made no progress against the city of Troy. Ironically, the

Iliad

focuses on a pitched battle on the Trojan Plain, although most of the war was fought elsewhere and consisted of raids. And the

Iliad

concentrates on only two months in the ninth year of the long conflict.

In that ninth year the Greek army nearly fell apart. A murderous epidemic was followed by a mutiny on the part of Greece's greatest warrior, Achilles. The issue, once again, was a woman: this time, the beautiful Briseis, a prize of war unjustly grabbed from Achilles by the Greek commander in chief, Agamemnon. A furious Achilles withdrew himself and his men from fighting. Agamemnon led the rest of the army out to fight, and much of the

Iliad

is a gory, blow-by-blow account of four days on the battlefield. The Trojans, led by Prince Hector, took advantage of Achilles' absence and nearly drove the Greeks back into the sea. At the eleventh hour, Achilles let his lieutenant and close friend Patroclus lead his men back into battle to save the Greek camp. Patroclus succeeded but overreached himself, and Hector killed him on the Trojan Plain. In revenge, Achilles returned to battle, devastated the enemy, and killed Hector. Achilles was so angry that he abused Hector's corpse. King Priam of Troy begged Achilles to give back his son Hector's body for cremation and burial, and a sadder but wiser Achilles at last agreed. He knew that he too was destined to die soon in battle.

The

Iliad

ends with the funeral of Hector. The

Odyssey

is set after the war and mainly describes the hard road home of the Greek hero Odysseus. In a series of flashbacks, it explains how Odysseus led the Greeks to victory at Troy by thinking up the brilliant trick of smuggling Greek commandos into Troy in the Trojan Horse, an operation which he also led. Achilles did not play a part in the final victory; he was long since dead. The

Odyssey

also shows Helen back in Sparta with Menelaus. But Homer leaves out most of the rest of the war. One has to turn to other and generally lesser Greek and Roman poets for additional detail.

Aeneas is a minor character in the

Iliad,

but the hero of a much later epic poem in Latin, written by Vergil, the

Aeneid.

Vergil makes Aeneas the founder of Rome (or, to be precise, of the Italian town that later founded Rome). But in Homer, Aeneas is destined to become king of Troy after the Greeks depart and the Trojans rebuild.

Now, consider how new evidence revises the picture: Much of what we thought we knew about the Trojan War is wrong. In the old view, the war was decided on the plain of Troy by duels between champions; the besieged city never had a chance against the Greeks; and the Trojan Horse must have been a myth. But now we know that the Trojan War consisted mainly of low-intensity conflict and attacks on civilians; it was more like the war on terror than World War II. There was no siege of Troy. The Greeks were underdogs, and only a trick allowed them to take Troy: that trick may well have been the Trojan Horse.

The

Iliad

is a championship boxing match, fought in plain view at high noon and settled by a knockout punch. The Trojan War was a thousand separate wrestling matches, fought in the dark and won by tripping the opponent. The

Iliad

is the story of a hero, Achilles. The Trojan War is the story of a trickster, Odysseus, and a survivor, Aeneas.

The

Iliad

is to the Trojan War what

The Longest Day

is to World War II. The four days of battle in the

Iliad

no more sum up the Trojan War than the D-day invasion of France sums up the Second World War. The

Iliad

is not the story of the whole Trojan War. Far from being typical, the events of the

Iliad

are extraordinary.

Homer nods, and he exaggerates and distorts too. But overly skeptical scholars have thrown out the baby with the bathwater. There are clear signs of later Greece in the epics; Homer lived perhaps around 700

B.C.

, about five hundred years after the Trojan War. Yet new discoveries vindicate the poet as a man who knew much more about the Bronze Age than had been thought.

And that is a key insight because Bronze Age warfare is very well documented. In Greece, archaeologists showed long ago that the arms and armor described by Homer really were used in the Bronze Age; recent discoveries help to pinpoint them to the era of the Trojan War. Like Homer, Linear B documents refer to a Greek army as a collection of warrior chiefs rather than as the impersonal institution of later Greek texts.

But the richest evidence of Bronze Age warfare comes from the ancient Near East. And in the 1300s and 1200s

B.C.

, Bronze Age civilization was international. Trade and diplomacy, migration, dynastic marriage, and even war all led to cultural cross-fertilization. So the abundant evidence of Assyria, Canaan, Egypt, the Hittites, and Mesopotamia puts in perspective the events of the

Iliad

and

Odyssey.

Some things in Homer that may seem implausible are likely to be true because the same or similar customs existed in Bronze Age civilizations of the ancient Near East. For example, surprise attacks at night, wars over livestock, iron arrowheads in the Bronze Age, battles between champions instead of armies, the mutilation of enemy corpses, shouting matches between kings in the assembly, battle cries as measures of prowess, weeping as a mark of manhoodâthese and many other details are not Homeric inventions but well-attested realities of Bronze Age life.

Besides recording Bronze Age customs, Homer reproduces Bronze Age literary style. Although he was Greek, Homer borrows from the religion, mythology, poetry, and history of the Near East. By composing in the manner of a chronicler of the pharaohs or the Hittites or Babylon's King Hammurabi, Homer lends an air of authenticity to his poem. For instance, Homer portrays champions on both sides carving paths of blood through the enemy as if they were supermenâor as if they were pharaohs, often described by Egyptian texts as superheroes in battle. Ironically, the more Homer exaggerates, the more authentic he is as a representative of the Bronze Age. And even the prominence of the gods in Homer, which drives most historians to distraction, is a Bronze Age touch, because writers of that era always put the gods at the heart of warfare. Belief in divine apparitions on the battlefield, conviction that victories depended on a goddess's patronage, and faith that epidemics were unleashed by offended deities are all well documented.

Could Homer have preserved the truth about a war that preceded him by five centuries? Not in all its details, of course, but he could have known the outline of the conflict. After all, a remarkably accurate list of Late Bronze Age Greek cities survived to Homer's day and appears in the

Iliad

as the so-called Catalog of Ships. And it survived even though writing disappeared from Greece between about 1180 and 750

B.C.

As for Trojan memories, writing did not disappear from the Near East, and trade routes between Greece and the Near East survived after 1200. Around 1000

B.C.

, Greeks crossed the Aegean Sea again in force and established colonies on the coast of Anatolia. Tradition puts Homer in one of those colonies or on a nearby Aegean island. If so, the poet could have come into contact with records of the Trojan Warâmaybe even with a Trojan version of the

Iliad.

In any case, writing is only part of the story. The

Iliad

and

Odyssey

are oral poetry, composed as they were sung, and based in large part on time-honored phrases and themes. When he composed the epics, Homer stood at the end of a long tradition in which poems were handed down for centuries by word of mouth from generation to generation of professional singers, who worked without benefit of writing. They were bards, men who entertained by singing about the great deeds of the heroic past. Often, what made a bard successful was the ability to rework old material in ways that were newâbut not too new, because the audience craved the good old stories.