The True Meaning of Smekday (29 page)

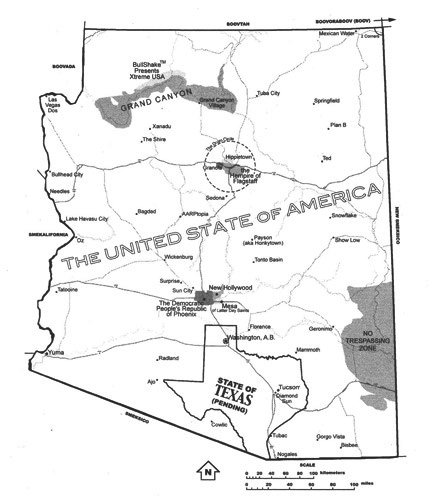

It went on and on like this. But I was more interested in the map.

I don’t know if I’ve ever bought that whole America-as-Melting-Pot thing, but now that the whole melting pot had been dumped in Arizona’s lap, I thought we might all mingle a little more. No.

The city of Payson was now something like ninety-nine percent white. There were really large numbers of senior citizens in places like Green Valley, Sun City, and Prescott. Prescott had been renamed AARPtopia, for some reason. Environmentalist and hippie types were living around Flagstaff. The incense should have tipped me off. There was a section of Tucson called Mallville, where a big group of the sort of girls who wished they could live at the shopping mall were now actually living in a shopping mall.

A lot of communities had already moved around because of wildfires. I guess Arizona just catches fire from time to time. So nearly all the Mormons in America had relocated from the northern border to a town called Mesa, around which they were building a very strong wall to keep out Phoenix.

Phoenix was apparently this shaky military dictatorship ruled by a warlord who called himself Beloved Leader the Angel of Death Sir Magnífico Excellente. Not his real name, I think.

J.Lo wanted to know where we were, and what it said next to my finger after I pointed.

“We live…” he said, “in the…Hempire of Flags Staff?”

“Actually, we might be in Hippietown.”

“Hippietown.”

“Explains all the naked people.”

There were some short human-interest stories in the back of the paper. It seemed that getting conquered and shipped to a new home where no one’s really in charge doesn’t bring out the best in most people. A surprising number of arguments were being settled with the kind of challenges you used to see only on reality shows. Proving you were the owner of a truck by eating the most cockroaches, for example. And since cockroaches vary in size a lot from place to place, let me just say that Arizona cockroaches are big enough to help you move.

Anyway.

Here are a few other things I learned the first couple weeks in Arizona:

—Most folks will steal if they can get away with it.

—Most people want to break other people’s things and roll cars over, but won’t unless their planets are invaded by aliens, or their basketball team wins the finals.

—About one in a hundred people resents having to wear clothes all the time.

—Alien invasions make people stick flags on

everything.

Not just American flags, either. The Jolly Roger made a real comeback around this time.

“Enough reading,” I said. “We have an appointment at the BMP.”

It was hot enough outside to make asphalt soft. That’s not a figure of speech. You could walk across one of the campus parking lots and feel your shoes sink like they were in dough. J.Lo said it was the sort of hot that made you want to gather animals in twos and keep them in a huge jar of water with holes poked in the lid. He had to keep his ghost costume wet all the time so his skin wouldn’t dry out. He happened to be dumping a bucket of water over his head, in fact, when we reached the steps of the Bureau of Missing Persons.

I was just about to partake of my daily exercise of visiting the BMP and shouting “Where’s my mom?!” and listening to Mitch tell me how I “need to show a little patience?!” while J.Lo walked around the office eating things. We were halfway up the steps when I heard Phil from the Lost List behind me.

“Gratuity! Gratuity!” he shouted. And even though we stopped and turned around, he kept shouting it anyway. When he reached us he was out of breath, and for good reason. Guys like Phil are not built for running. They are built for sitting in front of radios and for growing curly red Abe Lincoln beards that make their bald heads look wrong-side-up if you squint.

“Why…” Phil panted, “…are you squinting?”

“No reason. What’s wrong?” I asked. And then it hit me.

“Did you find my mom?”

Phil nodded. He nodded hard, like he was trying to shake a bug off his scalp. After that he had to sit down for a bit with his head between his knees.

“She’s near Tucson,” he said, after a minute. “Living in a casino. She’s so excited, she’s been looking for you for weeks.”

I hugged J.Lo and even hugged Phil. He smelled milky. Then we went inside the bureau to tell them to call off their search.

“I think you must be mistaken?” said Mitch, looking unsteady. His aides stood behind him as usual, and I wondered if they might finally have something to do.

“Nope,” said Phil. “We’re sure. She’s living in the Papago lands south of Tucson, in the Diamond Sun Casino.”

Mitch blustered. “Tucson? Tucson. I’m sorry, but we checked that area thoroughly? I checked it myself. I told Williams to check it myself.”

The hope in me flickered a little. I didn’t have much faith in Mitch, but what if he was right? I couldn’t get my hopes up.

Mitch hadn’t stopped talking. “Why, we even have some of our most reliable census figures from that area. Michaels! What portion of the new Tucson population have we on record?”

Michaels looked at his own clipboard.

“Forty-two percent, sir.”

“Forty…forty-two percent! Well, that’s really very good!” said Mitch. “You have to admit? That’s quite good so soon after Moving Day?”

It did seem pretty good.

“No,” said Michaels, “I’m sorry. That’s not a four, that’s one of those ‘less than’ signs. Less than two percent. I thought it was a four.”

Mitch exhaled. Phil and I exchanged looks. J.Lo sat in the corner licking the glue off a Post-it.

“Michaels,” said Mitch, “bring me the file on Lucy Tucci?”

Michaels hesitated. “There’s bound to be more than one,” he said.

“She’s thirty,” I offered. “Dark hair. Daughter named Gratuity.”

“Black,” said Mitch.

I coughed. “Black?”

“I’m sorry,” said Mitch. “Do you prefer African American?”

“Uh, no, I prefer you call her white, actually, because that’s what she is.”

“The file says she’s black.”

“Are you really arguing with me about this?”

Mitch looked tired. “I wrote down ‘black,’” he said.

“I didn’t tell you to write that,” I answered, and then I could see the whole thing. “Have you been telling everyone to look for a black woman this whole time?”

He had. The bureau had been sending out what they thought was Mom’s description, while the Lost List had been asking for a Lucy Tucci with a daughter named Gratuity.

Mitch tried to brush past it, and turned to Phil. “Where did you say she was?”

“Word is she’s living with a group in some place called the Diamond Sun Casino.”

“Diamond Sun…” said Mitch as he trailed his finger down a list of place names. I could tell he was trying hard to seem official, but his list was written on the back of a RavioliOs label. “Diamond…Diamond…here! Here it is. Diamond Sun Casino. Well, it’s in Daniel Landry’s district! Lucky you.”

“Daniel Landry?” I said. “Is that the guy who gave the talk I didn’t go to?”

“Sure. He’s the overseer there.”

“Overseer.”

Mitch nodded. “Mmm-hmm. You know, like the governor. Or mayor. I don’t know what he likes to be called. The leader of Ajo insists everyone call him King Awesome.”

“So every place has some kind of leader?” I asked. It had all happened so fast.

“Sure. Most of them are former state governors, or senators, or whatever. The president runs a little town called Rye.”

“Just a little town?”

“Yes…” said Mitch. “He’s not very popular anymore, because of the invasion. People assume it was his fault somehow. But we have to have leaders. We have to have government.”

“I guess,” I said.

“Daniel Landry’s district is far south of here,” he said, “on some former Indian land.”

“Indian land? Like a reservation?”

“That’s right.”

“Is this Dan guy an Indian?”

“I don’t think so, no. I’m pretty sure he’s white. He wasn’t a governor or anything before, but he’s really rich, so I imagine he’s a good leader.”

“Uh-huh. But he’s white,” I said. “The Indians elected a white guy?”

“Well…I don’t know. I imagine all the other people elected him. It’s mostly white folks living on the reservation now.”

I frowned. “And the Indians are okay with this?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well…it was a

reservation

,” I said. “It was land we promised to the Native Americans. Forever.”

Mitch looked at me like I was speaking in tongues. “But…we

needed

it,” he said.

I ran to a wall map. I didn’t care. I couldn’t leave fast enough.

“Sooo,” I said, “I take this road…seventeen? And then change to ten in Phoenix?”

“Mmmm. I don’t think you want to go through there. Phoenix is a bit…rough.”

“Rough?”

“Lawless,” Mitch said, “with violence and looting and so on. The government there gets overthrown every few days.”

“Fine. We’ll go around. We’ll go through the desert, I don’t care,” I chirped. “Thanks, Phil! Thanks, Mitch! J.Lo! We’re going!”

“Coming!” said J.Lo, grabbing a bottle of Wite-Out for the road.

“J.Lo?” said Mitch. “Wait! You can’t go by yourself!”

Or at least that’s what I think he said. We were so gone.

“Am I happy to have that sheet off,” said J.Lo for the third time. “Yes I am.”

“You might want to try to get used to it,” I said. “I think you’re gonna have to wear it for a while.”

He was making me nervous. Anyone could see us on the road. And Mitch had been right about Phoenix.

Even on the outskirts I could tell it was trouble. Gunfire sounded off like popcorn. Tires screeched in the distance. Someone somewhere was listening to Foghat really loud. I was raised to believe that cities like this one got visits from angels with flaming swords, so I was glad to be avoiding it.

There wasn’t much south of Phoenix. There was a town called Casa Grande that looked to be mostly outlet stores and tents. Somewhere around Dirt Farm, Arizona, we could see ostriches wandering around the sides of the highway.

“Mah! Big bird!” shouted J.Lo.

“We are

not stopping

,” I said. “I don’t care if there are ostriches, I don’t care if I don’t understand

why

there are ostriches. Someone can explain it to me later, we are

not stopping

.”

We were near Tucson now, and my heart was buzzing in my chest. Two glowing Boov ships whizzed overhead, and somewhere in the desert to the west came a very loud and bright explosion. All this seemed totally appropriate to me—I was excited beyond words and my insides felt like that part in the

1812 Overture

when all the cannons go off.

But this is what I also thought as I watched the waves of trash crash over the cracked and broken road: that for the rest of us, Arizona would always be one of our places now. It would be on the list of things we own in our heads. Don’t we all have this list? It’s like, everything that secretly belongs to us—a favorite color, or springtime, or a house we don’t live in anymore. We all gained Arizona by coming here, but for the people who already lived here, we could only take something away. I expected to return home to Pennsylvania one day as if I’d only stepped out for a fire drill. It would still be mine. But we’d turned Arizona into a motel room. It was our unmade bed.

“Look out!”

J.Lo screeched.

I swerved just in time to avoid a line of Gorg on foot, carrying rifles. One of them barked something in his own language, and thumped his chest.

“SEG FOY S’XAFFEF, LU F’GUBIQ YAZWI!”

“What was that all about?” I whispered.

“He said, ‘Get some glasses, you stupid monkey.’”

“No, I mean, why so many Gorg around? In our own state. They’re everywhere.”

“Four miles to go,” said J.Lo, noting a sign. He knew his numbers now, at least, and his directions. “Lots of fighting outo the southwest. The last huzzah for the Boov.”

“You think so?”

“I know this is so. Is almost over now.”

I was barely listening. I was only talking to distract myself. I felt a chill as I suddenly saw a billboard for the Diamond Sun Casino, next exit, right two miles.

“What did that say?” asked J.Lo.

I took a breath.

The outside of the Diamond Sun Casino could not have looked more ordinary. Okay, it was pink, but I thought these kinds of places were supposed to be glitzy, and this one squatted down the road like a big cake box. And there was a white wedding cake next to it—a huge tent, really, that glowed faintly inside. The gaudy sign by the road was unlit. But there was one light down below, waving back and forth under the chin of a round-eyed girl. I pulled up alongside her.

“Are you Gratuity?” she asked. “You are, aren’t you?”

I tried to answer but she was well on to other subjects.

“Is this your car? Does it float? Did

you drive yourself

? How old are you? Is that a ghost?”

I saw my opening and pounced.

“Can you take me to my mom?”

The girl frowned. “Mimom?”

“My. Mom,” I said.

“Oh, yeah, but they said not until after the meeting. The big meeting in the poker tent. Your mom’s kind of leading it.”