The Twilight of the American Enlightenment (3 page)

Read The Twilight of the American Enlightenment Online

Authors: George Marsden

These observations on the 1950s consensus outlook and the subsequent rise of the culture wars lead to the constructive purpose of this book, made explicit in the Conclusion, which is to reflect upon the problem of how American public life

might better accommodate religious pluralism. My argument,

in brief, is that the culture wars broke out and persisted in part because the dominant principles of the American heritage did not adequately provide for how to deal with substantive religious differences as they relate to the public domain.

The American paradigm for relating religion to public life was an unusual blend of enlightenment and Protestant ideals. In some ways it was the model of inclusivism and religious freedom. But because it also fostered an informal Protestant establishment, or privileges for mainstream Protestants in public life, there were always those who were less privileged, who were excluded or discriminated againstâsuch as Catholics, Jews, people of other world faiths, or those in smaller sectarian groups. Even in the more inclusive 1950s, mainstream Protestantism retained its preeminence in American public life. It is not surprising then that, by the 1970s, after the long-standing enlightenment-Protestant paradigm collapsed, mainstream America lacked the theoretical resources for constructing a more truly pluralistic way of dealing with the relationships of varieties of religions to public life. My contribution is to point to an alternative paradigm for thinking about the varieties of religious outlooks in the public sphere and the roles they play within that sphere.

Finally, let me say a word about point of view. One of the conventions of the mid-twentieth century was that authors and teachers normally did not identify their points of view but spoke as though they were neutral observers speaking on the basis of universal reason. Such practices reflected standards that went back to the eighteenth-century enlightenment, in which one was to hold forth on most topics on the basis of objective standards rather than from the point of view of one's

particular faith. Mid-twentieth-century commentators, unless they belonged to a peculiar party or sect, could speak as though they represented an outlook that, at least so far

as

fundamental assumptions were concerned, every educated person should share. Every critical thinker recognized, of course, that their opponents at least were smuggling in some biases. But even those who recognized the relativism inherent in much of modern thought rarely spelled out exactly what their own prejudices might be. Such conventions of discourse in fact helped to create the illusion that it was still possible to create a national consensus, despite residual sectarian differences.

In recent decades there has been greater recognition that, although there are common standards for rational discourse, arguments, and evidence, there is no one standard, underlying set of assumptions, including beliefs about the ultimate nature of reality and values, that all rational educated people can somehow be presumed to share. So, although many still follow the old convention of posing as though one were objective, it has become more acceptable these days to help out the reader or listener by identifying one's fundamental viewpoint from the outset.

My own point of view has been shaped most basically by my commitments as an Augustinian Christian.

10

Those commitments involve a recognition that people differ in their fundamental loves and first principles, and that these loves and first principles act as lenses through which they see everything else. At the same time, all humans, as fellow creatures of God, share many beliefs in common and can communicate through common standards of rational discourse. Furthermore, even

though I am an Augustinian Christian, I am also shaped in part

by many other beliefs and commitments that have been

common

in America in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries

. One of my goals in life has been to understand such characteristic American beliefs and to critically and constructively relate them to my religious beliefs. This book is an instance of that project. Much of it is about understanding a fascinating moment of the American experience, but that account leads to critical analysis and reflection on the question of the place that religion should have in that culture.

I hope that readers who hold other points of view, whether secular or religious, can nonetheless learn from what I present here. Although I write from a specific point of view, I do not differ from other writers or public intellectuals in that respect; I differ only in that I identify my viewpoint more explicitly than some of these other writers do. I hope that readers will benefit from that identification. It may allow them to learn from my analysis while taking into account the parts of my perspective with which they do not agree. That frank recognition of differences may then help them to better appreciate the understandings and insights that we can hold in common.

PROLOGUE

The National Purpose

In the late spring of 1960,

Life

, America's immensely

popular pictorial newsmagazine, claiming a readership of

25

million, published a “crucial U.S. debate” in a five-part series

on “The National Purpose.” The authors, a distinguished group, included not only professional observers of the national scene, headed by the legendary Walter Lippmann, but also men of practical affairs, such as David Sarnoff, head of the Radio Corporation of America. Others, such as poet Archibald MacLeish, recent two-time Democratic presidential candidate

Adlai Stevenson, and evangelist Billy Graham, were among the most

famous representatives of major areas of American life. It was unremarkable at the time that all the contributors were white males. It was just as unremarkable that the forum

included a clergyman, even though the clergyman was an ardent

evangelical (as well as being the only southerner in the mix).

1

Henry R. Luce, editor-in-chief of

Life

, explained in his foreword to the book version, which appeared later in the year, that, “more than anything else, the people of America are asking for a clear sense of National Purpose.” Providing a sort of

Norman Rockwell touch, he wrote that “a group of citizens may begin by talking about the price of eggs or the merits of

education, but they end by asking each other: what are we trying

to do overall? Where are we trying to get? What is the National Purpose of the U.S.A.?” America had become “the greatest nation in the world.” But the questions of the day were about what America would now “

do

with the greatness” and whether it was “great in the right way.”

Luce was one of the most influential opinion shapers in America, perhaps

the

most influential for the rank and file of the reading public. He was the head of a publishing empire that included not only

Life

but also

Time

(the most widely read print newsmagazine in the country in an era when print still held its place as the most respected medium),

Fortune

(the leading business weekly), and the new

Sports Illustrated

. Luce, a Yale graduate and the son of Presbyterian missionaries to China, was a wide-ranging and inventive thinker in his own right. America was his mission, and he tended to see the interests of God and country as going hand in hand. He invented the phrase “The American Century” in 1941, having prophesied prior to America's entry into the war that the nation was destined to become the leader of the free world. Americans had taken up that task and warmed to it. Now, almost twenty years later, the nation seemed to be drifting, and Luce wished to clarify where it should be heading.

The immediate context was that 1960 was an election year, and it was not clear exactly where the nation was headed. The recent years had been the first in a generation when the nation's purpose had not been clear. In the 1930s, the nation had

the clear goal of recovering from the Depression. Then came World War II, postwar rebuilding, and the Korean War. Ike had been president since 1953. He had led the “Crusade in Europe,” as he had titled his World War II memoir in 1948, but his presidency had been marked by his efforts to fend off the efforts of others to create a crusading or crisis atmosphere. Early in his presidency he had faced a challenge led by Senator Joseph McCarthy, who had attempted to turn anticommunism into a major domestic purge of anyone who had ever had leftist affiliations. The Cold War was at its height, and one of Ike's goals was to dampen the kind of zealotry that might lead to World War III. Moderation, however, came at a price: it could seem like lack of direction. Ever since the Soviet Union had launched its Sputnik satellite in 1957, critics of the administration had complained of a missile gap, saying that America was losing the space race. On the domestic front, there was a great deal of anxiety as to whether unprecedented prosperity and shallow popular culture might be causing the nation to lose its moral bearings as well.

In the original

Life

version of the series, the magazine's chief

editorial writer, John K. Jessup (Yale '28), set the stage for the

discussion. Amid lavish color illustrations of national icons, Jessup guided readers through the high points of American rhetoric, from the Declaration of Independence to Franklin D.

Roosevelt. The American project of building democracy had become, as Woodrow Wilson had declared, an international

project of “making the world safe for democracy.” Yet the

Cold War world of the 1950s seemed anything but safe, and

Americans seemed to be faltering on sustaining the

f

irst

principles upon which democracy was built. “Self-government

” had been a perennial American goal, he said, but today that idea, “that men can govern themselves in freedom under law,” might seem “too 18th Century for the world's needs today, or America's complex relation to it.” Furthermore, Jessup argued, “democracy . . . is not the highest value known to man.” Rather, it works only because it is grounded in “higher allegiances,” allegiances, that is, to “moral law.” Americans, he affirmed, have a “public love affair with righteousness,” because “our very right of self-government is derived from âthe Laws of Nature and of Nature's God.

'

” If Americans were to answer communism around the world in an effective way, then they ought to be able to provide a new articulation of John Locke and the founding fathers' principle that freedom is grounded in rights to property. But Jessup recognized that Americans had lost such a clear sense of purpose. He quoted a letter from

a US Air Force lieutenant to

Time

: “What America stands for is making money, and as the society approaches affluence, its members are left to stew in their own ennui.”

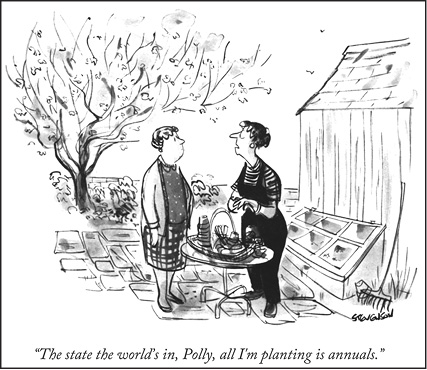

James Stevenson, April 30, 1960,

The New Yorker

Most of the other eight contributors to the

Life

series expressed concern that something like the lieutenant's views represented the national mood, or even the reality, all too well. Walter Lippmann, who had just turned seventy and was still widely regarded as America's wisest commentator, had been one of the most influential voices in saying America had lost its sense of purpose. Part of the problem, said Lippmann, was that earlier national purposes had been fulfilled. “We have reached a point,” he wrote, “in our internal development and in our relations with the rest of the world where we have ful

f

illed and outlived most of what we used to regard as the program of our national purposes.” The nation was like a man who had set out to cross the continent from New York and had gotten to Chicago, but was not sure which route ought to be taken from there.

Always one to keep the big picture in mind, Lippmann observed that “in the 15 years which have passed since the end of the second World War, the condition of mankind has changed more rapidly and more deeply than in any other period within the experience of the American people.” Among the most worrisome problems were world population growth, “a great and threatening agglomeration of people in cities,” and a “swift and radical change in the balance of power” that might foster worldwide revolutions. At the same time, people everywhere were experiencing “radical change in the technology of war and in the technology of industry.” The ever-present threat of

the obliteration by the bomb immensely raised the stakes in the discussion. On the home front, technology had changed almost every aspect of life. The advent of new mass media was particularly momentous, he said, “because it marks a revolution

in popular education and in the presentation of information

, and in the very nature of debate and deliberation.” It was thereby profoundly altering the assumptions on which a democratic society might be built.

Historian Clinton Rossiter framed the problem much as Lippmann did, suggesting that America was suffering from lost glory. “In our youth,” said Rossiter, “we had a profound sense of national purpose, which we lost over the years of our rise to glory.” Our “youthful sense of mission” was “in fact fulfilled nobly.” One only had to look at all the constitutional democracies in the world to see the truth of this claim. Now, however, America had become middle aged, Rossiter observed; striking a chord that resonated throughout the series, he added, “We are fat and complacent.” Whereas once we were

a people “on the make,” now we were a people who

“

âhas it made,' and we find it hard to rouse to the trumpet of sacri

f

ice

âeven if anyone in authority were to blow it.”

John Gardner, president of the Carnegie Foundation, did not think Americans had lost their ideals, but nonetheless conceded that there was “a danger of losing our bearings,” and that “part of our problem is how to stay awake on a full stomach.” The distinguished poet and playwright Archibald MacLeish saw the crisis as more deeply rooted, but he agreed that Americans still had a sense of purpose. “That something has gone

wrong in America,” he began, “most of us know.” The

problem

was our riches. “We have more Things in our garages and kitchens and cellars than Louis Quatorze had in the whole of Versailles.” Yet, despite “the materialism about which we talk so much,” our unease with it was a sign of hope. That was true especially among the “intelligent young,” whose current favorite whipping boys were the Madison Avenue ad men, who were said to “persuade us to wallow in cosmetics and tail-

f

in cars.” MacLeish added presciently, “We may be drowning in Things,

but the best of our sons and daughters like it even less than we do.”

Billy Graham warned that the nation's flaws were potentially fatal, and he challenged the widespread view that the problems might be self-correcting. America, he began, was like a man with whom he had played golf a few months earlier, who had appeared to be healthy, but since had died of cancer. In the midst of affluence, “America is said to have the highest per capita boredom of any spot on earth.” That emptiness was reflected in youth culture in which “rebels without a cause” were rebelling from conformity for the sake of rebelling. Only change from the inside out, or Christian conversion, could transform people in the way that was necessary to renew the culture. Then Americans could recapture their individualism, patriotism, discipline, and courage, qualities that had “made us the greatest nation in the world.” Ultimately, though, America's strength must be used for altruistic ends. The nation must share its wealth, said Graham. It should attack “the worldwide problems of ignorance, disease and poverty.”

One of the most striking features of the series was how many of the authors worried that Americans' self-indulgent

materialism might be making them unfit to be leaders of the free world in the fight against communism. That fight, after all, provided the most urgent context for the anxieties over national purpose. Graham quoted the famed diplomat George Kennan to make the point that a country “with no highly developed sense of national purpose, with the overwhelming accent of life on personal comfort, with a dearth of public services and a surfeit of privately sold gadgetry” could simply not compete with the Soviet Union. Adlai Stevenson quipped, “With the supermarket as our temple and the singing commercial as our litany, are we likely to fire the world with an irresistible vision of America's exalted purposes and inspiring way of life?”

In offering solutions, most of the authors agreed that the

national ideals themselves were adequate and that there was

no

easy

f

ix for the perils of prosperity, but that what was needed

was a sort of pragmatism that would rely on practical problem

-solving rather than on grand ideological abstractions. Clinton Rossiter argued that in the face of the nuclear threat “it has now become the destiny of this nation to lead the world prudently and pragmatically” toward a world “government having power to enforce peace.” Albert Wohlstetter, of the Rand Corporation, the one scientist in the group, who had recently been scientific adviser in arms talks with the Soviets, was skeptical of the talk about “national purpose,” because there were multiple purposes. For example, the nation needed both economic growth and nuclear deterrence. Wohlstetter went on to show how these two objectives could be compatible. James “Scotty” Reston, whose

New York Times

editorial on

the topic was added to the original nine in the book version, best stated the need for the primacy of pragmatism, saying, “If

George Washington had waited for the doubters to develop a sense of purpose in the 18th century, he'd still be crossing the

Delaware.” Reston proclaimed that he was “all for self-direction and self criticism,” but in fact believed it was more urgent to address the nation's practical problems. America still had the ideals and resources it needed to solve them. Things got done with effective leaders. And the upcoming election, he reminded everyone, would provide the country with the opportunity to find such a leader.