The Underground Reporters (13 page)

Not long after that, John entered his kitchen to find his parents reading a sheet of paper. “What is it?” he asked. These days, orders arrived at the homes of Jewish families on a regular basis.

The Star of David that all Jews were forced to wear.

His father cleared his throat before speaking. “The Nazis have closed the swimming hole,” he finally blurted. “I’m sorry, John,” he added, seeing the shocked look on his son’s face. “I’m afraid you and the other children will no longer be able to go there.”

John could not believe what he was hearing. How could his playground, the place where he and his friends had enjoyed their best times, be off-limits to him? There would be no more chess tournaments and no more soccer games. He turned away from his parents. He began to understand, in a way he never had before, how the Nazis were closing in on them all.

One month later, even Mr. Frisch’s classes were suspended.

The days felt endless for John. He wanted to be with his friends. From time to time, he was still able to get together with Beda and play chess or other indoor games. But there were no more tournaments by the swimming hole, and no more outings.

CHAPTER

19

T

HE

L

AST

D

AYS OF

K

LEPY

S

EPTEMBER

1941

In September 1941, the twentieth edition of

Klepy

was published. Though Ruda was proud that the magazine had reached this milestone, he was also very troubled.

Ruda always listened carefully when the adults around him talked. He listened to radio broadcasts and read newspaper reports whenever he could. His experience as a reporter had taught him to be a keen observer of details, to ask probing questions, and to read between the lines in order to determine the truth. From letters that other Jewish families had received, he knew about the ghettos in many European cities. There, food was in such short supply that people were starving to death. He could see how things were getting worse for Jews all over Europe.

“How long can we keep writing?” he asked Irena one day as they sat together. “How long can we pretend to be optimistic about the future when things get scarier day after day?”

Irena smiled sadly at her younger brother. He had always been sensitive and perceptive. His intuition had pushed him to think of a way to

inspire the youth of Budejovice through the creation of

Klepy.

That same intuition was now crashing down on him, making him feel more and more disheartened.

“I don’t know if I can keep writing,” he continued. “Each time I hear about prisons and work camps around Europe, I think it’s only a matter of time before we are all sent away.”

Klepy

was the most meaningful task he had ever undertaken. It was a mission that had given his life purpose and focus. Ruda knew that he and the other reporters had achieved everything they had originally set out to do –

Klepy

’s reputation had gone far beyond Ruda’s dreams. But now he felt he had completed his mission. He felt he could no longer write. It was time to step down as the editor.

He gathered his reporters together for a final meeting. “It’s finished for me,” he said. “I’ve written everything I can write.”

At first, his team protested. “You can’t stop, Ruda.”

“Nobody can replace you.”

“The work is too important.”

Ruda agreed, but he said, “I’ve had enough. Besides, I’ve really done everything I set out to do. Look around. People feel proud of our community and proud to be Jewish. I believe that has a lot to do with our commitment to

Klepy.”

The boys and girls nodded. It was true that there was a strong sense of pride within the Jewish community of Budejovice. The Nazis might have stripped away their property and belongings, but not who they were inside.

Klepy

had given people dignity in these terrible times.

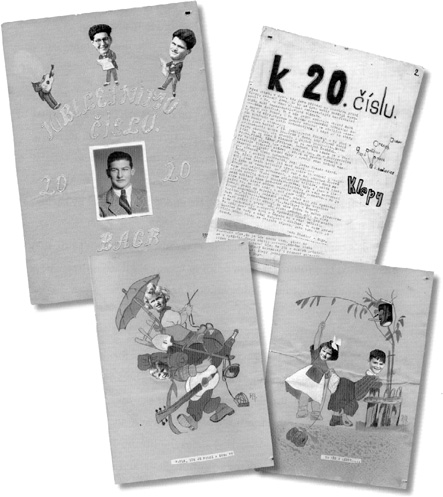

Top left: The cover of the twentieth edition, with the original editorial team. Ruda is in the middle, with Rudi Furth (top center) and Jiri Furth (top right). The missing photo (top left) is that of Karli Hirsch. Top right: In the twentieth edition of

Klepy,

Ruda steps down as editor and encourages everyone to keep their spirits high. Bottom: Photo/drawings from the twentieth edition of

Klepy.

“What will happen to the newspaper?” asked Reina Neubauer.

“Maybe someone else wants to take it over,” suggested Ruda. “I’m happy for anyone to do that, if they want.”

That evening, Ruda sat down to write his final editorial. In it, he returned to the original purpose of

Klepy:

“To give expression to the pride of the Jewish youth of our town; to energize them to physical and mental achievements.… For two summers we have played sport, established friendships, and kept up our spirit.” He ended his editorial by saying, “We hope to meet you again.…”

Ruda’s comments were strong but a bit sad – as if he wasn’t sure that there would be a future for

Klepy

or for its creators. All across town, people read the editorial and felt desolate and uncertain.

When the winter of 1941 arrived, there were two more issues of

Klepy.

Milos Konig, a young boy who had written articles for the newspaper, took Ruda up on his challenge to keep it going. He became the editor for these last two issues. But they were not the same as the old

Klepy.

There were fewer jokes, and the articles were more serious as they looked back at past pleasures and worried about the future. There were wistful poems about memories of the swimming hole, and solemn proverbs that reminded families about sacrifice.

Reina arrived at Ruda’s home to drop off the final edition. “We can’t do it anymore,” he said. “It’s no longer safe for us to meet, and it’s impossible to gather information for articles. We can’t even buy supplies. On

behalf of all the reporters of

Klepy,

I’m bringing the last edition to you.”

A boy named Milos Konig managed the last two editions of

Klepy

and wrote the editorials.

Ruda took the copy from Reina’s hands with a sinking heart. He missed working on the newspaper. He missed being its leader and editor. But most of all, he missed the freedom it had represented.

“If anything happens to us, this collection must stay together,” Reina continued. “We’re trusting you to find a way to do that.”

Ruda nodded, shook hands with Reina and closed the door. He looked down at the last edition of his treasured newspaper. Then he moved to the kitchen table, reached underneath it, picked up the box that held the entire collection of

Klepy,

and reverently placed the last edition on the top of the pile.

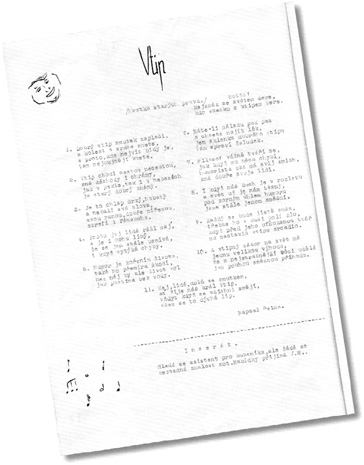

In the twentieth edition, Reina Neubauer wrote this poem, entitled, “The Joke.” One verse reads,

So people, down with sadness!

Long lives the King of Joke.

As long as we all can laugh,

It is easier to cope.

CHAPTER

20

D

EPORTATION

N

OVEMBER

1941

By the fall of 1941, Adolf Hitler had finalized his plan to kill all Jewish people in Europe. This plan was called “The Final Solution.” Concentration camps were set up across Germany and Poland. These “camps” were actually prisons built for the specific purpose of killing as many Jews as possible, as quickly as possible. Six of them would become primary killing sites: Auschwitz, Majdanek, Belzak, Sobibor, Treblinka, and Chelmno. As hostility toward Jews intensified, more ghettos were formed in towns and cities. These became collection centers where Jews were held until they could be deported to the concentration camps.

Up until then, the Jewish families of Budejovice had heard rumors of these deportations, but only from distant places. But now, in nearby cities and towns, families were being arrested and sent away. Frances Neubauer heard about this from her aunt’s home in Brno, where Jews were already being deported. If her aunt was sent away, Frances would likely be sent with her. It would be better if she went home to her family. Just

before her fifteenth birthday, in November 1941, Frances boarded a train to return to Budejovice. She came home in the last car of the train, the one set aside for Jewish passengers. She had not seen her parents, or Beda and Reina, in over a year.

When her father saw her for the first time, he smiled lovingly and sadly. “I sent away a girl, and you’ve returned as a young lady,” he said as he hugged and kissed his daughter. There was no way they could make themselves safe. But if anything was going to happen to them, at least they were together

To save money, the Neubauers had moved to a small apartment that they shared with two other Jewish families – a total of eleven people were now living in one crowded space. The only toilet was in the hallway. In the kitchen, the women fought constantly about what to cook and how to prepare it. In the end there was not much to fight about, since there was so little food to begin with.

On December 7, 1941, the war took a dramatic turn. Japan attacked the fleet of American warships in Pearl Harbor, in the United States. Japan was a strong ally of Germany, and Japanese leaders thought that if they destroyed the U.S. fleet, they would be able to expand their empire into Pacific territories. It was a serious mistake. On December 11, 1941, the outraged United States declared war on Japan, and then on Germany as well. Without the power of the United States, Britain and her allies had been suffering terrible losses, and it had seemed all too likely that Hitler would rule the entire European continent, including Great Britain. Over the next few months, though, the balance of power

would finally begin to shift away from Germany, and toward the United States and her new allies.

But it would take time to change the tide of war and turn back the German troops. In the meantime, all across Europe, Jews continued to lose their lives at the hands of the Nazis.