The Underground Reporters (10 page)

Top: In this editorial (Uvodem), Ruda appeals to readers to contribute articles to

Klepy.

Bottom: At the end of every edition, in a section called Listarna (editor’s comments), Ruda thanked those who had contributed articles.

Ruda lived on this street in Budejovice, pictured today.

Tirelessly Ruda and his friends sifted through the many jokes and word puzzles that had been submitted, narrowing down the list of items that would appear in the next issue, in the humor section. Poems were also popular, so Ruda selected the ones that would complement this edition. Stories were next, along with a sports column. Now that it was fall, and the sporting events had ended, the sports column was a popular reminder of warmer days.

The last step was to end the magazine on a high note. This was also Ruda’s job. He was in charge of writing a section called “Listarna” (editor’s comments) at the end of every edition, in which he thanked those who had submitted stories and articles. He also added a comment or two about the various contributions. He knew it was important to thank everyone for writing. That was the only way to encourage others to submit their work. And more submissions were needed to keep the newspaper going.

There was so much to think about. They worked feverishly, choosing where the pictures would go and creating headings and captions. Finally, it was time to start typing. Ruda bent over the typewriter and pecked out the handwritten stories and articles. No one noticed the time passing as the pages were typed and retyped. Pictures were pasted in to enhance the stories. Each page had to be proofread several times. Ruda wanted no mistakes in

Klepy.

Finally, Ruda stood up and smiled, and shook hands with his friends. They slapped each other on the back, hugged, and congratulated themselves. The fifth issue of

Klepy

was ready to be circulated.

CHAPTER

13

R

UDA’S

I

NVITATION

John left early one morning for Mr. Frisch’s house. The skies were dark and menacing, and the clouds looked ready to explode with rain. Nothing was worse than a cold, rainy day that couldn’t decide if it was fall or winter and ended up being a mess of both, he thought. He pulled the collar of his jacket up around his neck. The jacket was old and fraying at the sleeves. It was a hand-me-down from Karel, but it was beginning to feel tight on John too. He picked up his pace. He would get soaked if he didn’t hurry. Sure enough, the first icy drops were falling as he turned the corner to school. By the time he arrived at Mr. Frisch’s home, it was pouring.

Inside, John caught Beda’s eye and the two of them moved to desks in a corner of the living room. They pulled out their notebooks and waited for Mr. Frisch to begin his lesson. John yawned as the teacher’s eyes gazed sternly in his direction. The day had barely started and he was already feeling restless. “Attention, students. Quiet, please.” The class settled as Mr. Frisch began to speak. “Before we begin today, Ruda Stadler

has asked if he might have a few moments to speak with you.” With that, Mr. Frisch turned to Ruda, who had entered the living room and moved to stand at the front.

In this editorial Ruda asks for articles that are more serious. He writes, “So now Issue 4 of

Klepy

has been released. Most credit belongs to those who contribute, since without them there could not be an issue. However, many haven’t written a line for

Klepy

. Now, I would also appreciate receiving contributions that deal with events that are more serious. Certainly one can come up with a lot of ideas that could become a subject for open discussion in

Klepy.”

John brightened. He liked Ruda, and had always looked up to him because of his great skills in sports. Anyone who could smash a volleyball like Ruda was a hero in John’s eyes. But these days, he was also in awe of Ruda because of

Klepy.

In fact, most of the city’s Jewish families appreciated Ruda and his determination to keep

Klepy

going.

Ruda faced the children. “Raise your hand if you’ve read

Klepy.”

They all held up a hand, and some of the children snickered softly.

What a silly question,

thought John.

Of course we’ve all read it.

“Raise your hand if you like what we’ve written so far.”

Again, every child lifted a hand high. Even Mr. Frisch raised his

hand. “The reason I’m here,” continued Ruda, “is to appeal to each and every one of you to join our writing team. We can only keep

Klepy

going if each one of you in this room becomes a reporter. It’s not enough to just read the newspaper. And it’s not okay to read what someone else has written and sit back and criticize it. You have to write as well. We need more articles. If this newspaper is to continue to grow, then everyone has to become involved.”

Ruda paused, allowing his words to sink in. John glanced over at Beda, whose eyes were shining. Beda loved writing. This was the invitation he was looking for. “What kind of articles do you need?” asked Tulina.

“Anything,” Ruda replied. “Write something about your family or your pet. Write something about the swimming hole. Everyone loves to read about our playground. I know the newspaper was easier to produce during the summer, when we were all together. But now, more than ever, we need a way to stay connected.

Klepy

can help us do that.

“Every day,” Ruda continued, “there are new rules about what we can and can’t do. Well, the one thing that can’t be restricted is our minds. No one can forbid us to think. So I’m asking you to use your minds and write something.”

“Can we make drawings?” Beda asked.

Ruda nodded. “Of course. Draw pictures or cartoons. Write about people you like or people who are interesting to you.” He looked over at John and Tulina, and John blushed furiously. It seemed that others knew about his crush on her. “Write jokes or comics. Bring all your articles to my home. I promise you, my editors and I will read everything

you submit, no matter how long or short.” He paused and moved closer to the students. “Think about seeing your name in print, and how it will make you feel. Ours is a small newspaper, but it can have a positive influence on our lives. I know that each of you has something to contribute – something important to say.” With that, he thanked Mr. Frisch for allowing him to speak, and left the house.

The children buzzed with excitement. Several pulled out notebooks and began writing. Ruda had inspired them so much that they wasted no time getting started. As for John, his head was spinning. He wanted to write something too. Could he become a contributing reporter? He picked up his notebook, staring down at the blank page and imagining what his first contribution might be.

CHAPTER

14

A N

EW

R

EPORTER

“It’s here!” yelled John, bursting through the door of his apartment with another issue of

Klepy

in his hands.

“Wonderful!” his mother responded. “Let me have a look.”

John shook his head. “I’m first,” he said, and moved off into a corner where he could read the newspaper uninterrupted. This edition of

Klepy

contained his first article, and he wanted to look at it by himself. He thumbed through the pages, pausing to read some of the stories. His mother stood nearby impatiently, wanting her turn at the magazine. Finally, John turned a page and there it was.

H

OW MY FATHER, A DOCTOR, FIXED MY HEAD

By John Freund, 10 years old

“Mom, please give me money. I need a haircut.”

“You better go to Dad, son. He will give you some.”

So I went to see my father. He was sitting at a desk. “You know, these are bad times, and we don’t have much money. As

a doctor, I’m used to examining heads. I will cut your hair and shave your neck as well.”

John’s first article in

Klepy,

“How my father, a doctor, fixed my head.”

And so it began. Dad took the knife and began to shave the back of my neck. That was not bad. Then he took a pair of scissors and started to hack at me. You would not believe what a doctor can do … “Ouch!” I cried out suddenly as my father cut into my ear. My mom, in the kitchen, heard the cry and came running. She opened the door and almost fainted. I had almost no hair left. I ran to the mirror. For a moment, I did not know whether to laugh or cry. My mother began to shout at my dad, until he gave in and handed me a quarter for the barber.

When I entered the barbershop and took off my cap, the barber screamed, “What kind of artist cut your hair?”

Fortunately, the barber was able to fix what the doctor had destroyed!

John was thrilled to have become a contributing reporter for

Klepy.

He quickly turned to the back of the paper, to the sign-off sheet, to write in his name and his comments. He glanced down at the comments that were already there. Most people loved

Klepy,

and their comments were full of high praise. Some people had suggestions for what they wanted to see in the newspaper. Some even criticized the paper and its articles.

John took a pen and began to write: “First class. The newspaper gets

better and better. Soon there will be one hundred pages, which is good. I can’t wait for that to happen.”

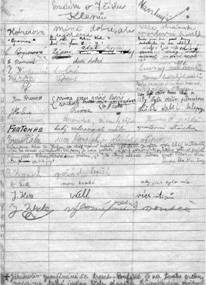

Every edition of

Klepy

included a sign-off sheet asking readers to sign their name and comment on that edition. On this sheet John writes, “First class. The newspaper gets better and better. Soon there will be one hundred pages, which is good.”

Then he passed the newspaper to his parents so that they could have their chance to read it, and to record their comments. They laughed when they read the article about the haircut.

“I never knew you were such a wonderful writer,” his mother said, proudly.