The Victorian Internet (6 page)

Read The Victorian Internet Online

Authors: Tom Standage

I

N THE UNITED STATES, Morse and his associates faced similar apathy. Even though the use of the experimental Washington-Baltimore

telegraph was free, members of the public were quite content just to come and see it, and watch chess games played between

the leading players of each town over the wires. But the telegraph wasn't regarded as being useful in day-today life. "They

would not say a word or stir and didn't care whether they understood or not, only they wanted to say they had seen it," Vail

complained to Morse.

Before long, religious leaders in Baltimore expressed their doubts about the new technology, which was too much like black

magic for their liking, prompting Henry J. Rogers, the Raltimore operator, to warn Vail that "if we continue we will be injured

more than helped." Aware of the importance of keeping public opinion on their side, they decided to call a halt to the frivolous

chess games and restrict use of the line to congressional business.

In June 1844, Morse went back to Congress to press for the extension of the line from Baltimore to New York. He presented

to the House several examples of the benefits of the telegraph. A family in Washington, for instance, had heard a rumor that

one of their relatives in Baltimore had died, and asked Morse to find out if it was true. Within ten minutes they had their

answer: The rumor was false. Another example concerned a Baltimore merchant who telegraphed the Bank of Washington to verify

the creditworthiness of a man who had written him a check. But Congress still adjourned for the summer without making a decision.

In December, Morse appealed to the House again, pointing out that the telegraph would be much more useful with more stations,

and advocating the wiring up of the country's major cities.

Again, he gave examples of the benefits of the Washington-Baltimore line; in a case similar to that of John Tawell, police

in Baltimore had been able to arrest a criminal as he stepped from an arriving train, after his description was telegraphed

to them by the police in Washington. By this stage, the proceedings of Congress were being transmitted for inclusion in the

Baltimore papers, and one or two farsighted businessmen were starting to use the line. But again, nothing happened.

Morse, disheartened by the government's lack of interest, turned to private enterprise. He teamed up with Amos Kendall, a

former politician and journalist, whom he appointed as his agent. Kendall proposed the construction of lines along major commercial

routes radiating out from New York using private money, with Morse and the other patent holders to be awarded 50 percent of

the stock of each telegraph company formed in return for the patent rights. In May 1845, the Magnetic Telegraph Company was

formed, and by the autumn, lines were under construction toward Philadelphia, Boston, and Buffalo, and westward toward the

Mississippi.

Meanwhile, the postmaster general, Cave Johnson, the former congressman who had ridiculed the whole idea of the telegraph

two years earlier, decided that the time had come for the government to try to get some of its money back from the Washington-Baltimore

telegraph. He imposed a tariff of one cent for four characters, and on April 1, 1845, the line was officially opened for public

business. It was a financial failure: The line took one cent during its first four days of operation. A man with only a twenty-dollar

bill and one cent entered the Washington office and asked for a demonstration, so Vail offered him a half cent's worth of

telegraphy: He sent to Rogers in Baltimore the digit 4, which was short for "WHAT TIME IS IT?" and the answer, the digit 1,

meaning one "O'CLOCK," came back. This was hardly an impressive demonstration, since it was the same time in both cities,

and the customer left without even asking for his half cent change.

During the fifth day the telegraph took twelve and a half cents, and revenues rose slowly to reach $1.04 by the ninth day—hardly

big business. After three months the line had taken in $193.56 but had cost $1,859.05 to run. Congress decided to wash its

hands of the whole affair and handed the line over to Vail and Rogers, who agreed to maintain the line at their own expense

in return for the proceeds. In light of this development, Kendall's optimism that the telegraph would take off seemed unfounded.

But he knew what he was doing. By the following January, the Magnetic Telegraph Company's first link was completed between

New York and Philadelphia, and Kendall placed advertisements in the newspapers at both ends an nouncing the opening of the

line on January 27- The fee for a message was set at twenty-five cents for ten words.

The receipts for the first four days were an impressive $100. "When you consider," wrote the company treasurer, "that business

is extremely dull, we have not yet the confidence of the public and that on two of the four days we have been delayed and

lost business in Philadelphia through mismanagement, you will see we are all well satisfied with results so far. In one month

we shall be doing a $50 business a day."

I

n BRITAIN, the tide had also turned for Cooke, who had scored a notable victory: He had actually persuaded the Admiralty

to sign a valuable contract for an eighty-eight-mile electric telegraph link between London and Portsmouth. Clearly, if he

could convince the Admiralty, he could convince anyone. The success of the line led to more business, and proposals were advanced

for a telegraph linking London with the key industrial centers of Manchester, Birmingham, and Liverpool—which would have obvious

commercial applications. Cooke had also signed up more railway companies, and hundreds of miles of line were soon under construction.

The arrest of Tawell had brought the electric telegraph to the attention of John Lewis Ricardo, a member of Parliament and

a prominent financier. He purchased a share of the patent rights to the telegraph from Cooke and Wheatstone, clearing Cooke's

debts and valuing their business at a hefty £144,000. In September 1845, Cooke and Ricardo set up the Electrical Telegraph

Company, which bought out Cooke and Wheatstone's patent rights altogether.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the electric telegraph was finally taking off.

"We are one!" said the nations, and hand met hand, in a thrill electric from land to land.

—from "The Victory," a poem written in tribute to

Samuel Morse, 1873

N

O INVENTION of modern times has extended its influence so rapidly as that of the electric telegraph," declared

Scientific American

in 1852. "The spread of the telegraph is about as wonderful a thing as the noble invention itself."

The growth of the telegraph network was, in fact, nothing short of explosive; it grew so fast that it was almost impossible

to keep track of its size. "No schedule of telegraphic lines can now be relied upon for a month in succession," complained

one writer in 1848, "as hundreds of miles may be added in that space of time. It is anticipated that the whole of the populous

parts of the United States will, within two or three years, be covered with net-work like a spider's web."

Enthusiasm had swiftly displaced skepticism. The technology that in 1845 "had been a scarecrow and chimera, began to be treated

as a confidential servant," noted a report compiled by the Atlantic and Ohio Telegraph Company in 1849. "Lines of telegraph

are no longer experiments," declared the

Weekly Missouri Statesman

in 1850.

Expansion was fastest in the United States, where the only working line at the beginning of 1846 was Morse's experimental

line, which ran 40 miles between Washington and Baltimore. Two years later there were approximately 2,000 miles of wire, and

by 1850 there were over 12,000 miles operated by twenty different companies. The telegraph industry even merited twelve pages

to itself in the 1852 U.S. Census.

"The telegraph system [in the United States] is carried to a greater extent than in any other part of the world," wrote the

superintendent of the Census, "and numerous lines are now in full operation for a net-work over the length and breadth of

the land." Eleven separate lines radiated out from New York, where it was not uncommon for some bankers to send and receive

six or ten messages each day. Some companies were spending as much as $1,000 a year on telegraphy. By this stage there were

over 23,000 miles of line in the United States, with another 10,000 under construction; in the six years between 1846 and

1852 the network had grown 600-fold.

"Telegraphing, in this country, has reached that point, by its great stretch of wires and great facilities for transmission

of communications, as to almost rival the mail in the quantity of matter sent over it," wrote Laurence Turn-bull in the preface

to his 1852 book,

The Electro-Magnetic

Telegraph.

Hundreds of messages per day were being sent along the main lines, and this, wrote Turnbull, showed "how important an agent

the telegraph has become in the transmission of business communications. It is every day coming more into use, and every day

adding to its power to be useful."

Arguably the single most graphic example of the telegraph's superiority over conventional means of delivering messages was

to come a few years later, in October 1861, with the completion of the transcontinental telegraph line across the United States

to California. Before the line was completed, the only link between East and West was provided by the Pony Express, a mail

delivery system involving horse and rider relays. Colorful characters like William "Buffalo Bill" Cody and "Pony Bob" Haslam

took about 10 days to carry messages over the 1,800 miles between St. Joseph, Missouri and Sacramento. But as soon as the

telegraph line along the route was in place, messages could be sent instantly, and the Pony Express was closed down.

In Britain, where the telegraph was doing well but had not been quite so rapidly embraced, there was some bemusement at the

enthusiasm with which it had been adopted on the other side of the Atlantic. "The American telegraph, invented by Professor

Morse, appears to be far more cosmopolitan in the purposes to which it is applied than our telegraph," remarked one British

writer, not without disapproval. "It is employed in transmitting messages to and from bankers, merchants, members of Congress,

officers of government, brokers, and police officers; parties who by agreement have to meet each other at the two stations,

or have been sent for by one of the parties; items of news, election returns, announcements of deaths, inquiries respecting

the health of families and individuals, daily proceedings of the Senate and the House of Representatives, orders for goods,

inquiries respecting the sailing of vessels, proceedings of cases in various courts, summoning of witnesses, messages for

express trains, invitations, the receipt of money at one station and its payment at another; for persons requesting the transmission

of funds from debtors, consultation of physicians, and messages of every character usually sent by the mail. The confidence

in the efficiency of telegraphic communication has now become so complete, that the most important commercial transactions

daily transpire by its means between correspondents several hundred miles apart."

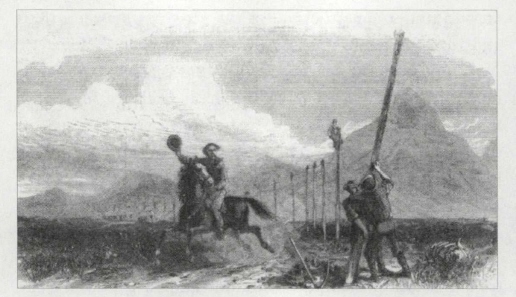

Construction of the transcontinental telegraph along the route of the Pony Express, 1861. When the telegraph line was complete,

the horse-and-rider relay service was rendered obsolete.

Just as the old optical telegraphs were understood to be the preserve of the Royal Navy, the new electric telegraph was associated

in British minds with the railways. By 1848, about half of the country's railway tracks had telegraph wires running alongside

them. By 1850, there were 2,215 miles of wire in Britain, but it was the following year that things really took off. The domination

enjoyed by Ricardo and Cooke's Electric Telegraph Company came to an end as rival companies arrived on the scene, and thirteen

telegraph instruments based on a variety of designs were displayed at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, fueling further

interest in the new technology. These developments gave the nascent industry the jolt it needed to emerge from the shadow

of the railways.

The telegraph was doing well in other countries, too. By 1852, there was a network of 1,493 miles of wire in Prussia, radiating

out from Berlin. Turnbull, who compiled a survey of telegraph systems around the world, noted that instead of stringing telegraph

wires from poles, "the Prussian method of burying wires beneath the surface protects them from destruction by malice, and

makes them less liable to injury by lightning." Austria had 1,053 miles of wire, and Canada 983 miles; there were also electric

telegraphs in operation in Tuscany, Saxony and Bavaria, Spain, Russia, and Holland, and networks were being established in

Australia, Cuba, and the Valparaiso region of Chile. Competition thrived between the inventors of rival telegraph instruments

and signaling codes as networks sprung up in different countries and the technology matured.

Turnbull was pleased to note that the wonders of the telegraph had managed to rouse the "lethargic" inhabitants of India into

building a network. He was even ruder about the French, whom he described as "inferior in telegraphic enterprise to most of

the other European companies." This view was unfounded, for the French had not only invented the telegraph but named it too.

But their lead in the field of optical telegraphy had actually worked against them, and the French were reluctant to abandon

the old technology in favor of the new. Francois Moigno, a French writer, compiled a treatise on the state of the French electric

telegraph network, whose size he put at a total of 750 miles in 1852—and which he condemned for leading to the demise of the

old optical telegraphs.

S

ENDING AND RECEIVING messages—which by the early 1850s had been dubbed "telegrams"—soon became part of everyday life for

many people around the world. But because this service was expensive, only the rich could afford to use the network to send

trivial messages; most people used the telegraph strictly to convey really urgent news.

Sending a message was a matter of going into the office of one of the telegraph companies and filling in a form giving the

postal address of the recipient and a message-expressed as briefly as possible, since messages were charged by the word, as

well as by the distance from sender to receiver. Once the message was ready to go, it would be handed to the clerk, who would

transmit it up the line.

Telegraph lines radiated out from central telegraph offices in major towns, with each line passing through several local offices,

and long-distance wires linking central offices in different towns. Each telegraph office could only communicate with offices

on the same spoke of the network, and the central telegraph office at the end of the line. This meant that messages from one

office to another on the same spoke could be transmitted directly, but that all other messages had to be telegraphed to the

central office and were then retransmitted down another spoke of the network toward their final destination.

Once received at the nearest telegraph office, the message was transcribed on a paper slip and taken on foot by a messenger

boy directly to the recipient. A reply, if one was given, would then be taken back to the office; some telegraph companies

offered special rates for a message plus a prepaid reply.

Young men were eager to enter the business as messengers, since it was often a stepping-stone to better things. One of the

duties of messenger boys was to sweep out the operating room in the mornings, and this provided an opportunity to tinker on

the apparatus and learn the telegrapher's craft. Thomas Edison and steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie both started

out as telegraph messenger boys. "A messenger boy in those days had many pleasures," wrote Carnegie in his autobiography,

which includes rather rose-tinted reminiscences of the life of a messenger boy in the 1850s. "There were wholesale fruit stores,

where a pocketful of apples was sometimes to be had for the prompt delivery of a message; bakers and confectioners' shops

where sweet cakes were sometimes given to him. He met very kind men to whom he looked up with respect; they spoke a pleasant

word and complimented him on his promptness, perhaps asking him to deliver a message on the way back to the office. I do not

know a situation in which a boy is more apt to attract attention, which is all a really clever boy requires in order to rise."

Though its business was the sending and receiving of messages, much like e-mail today, the actual operation of the telegraph

had more in common with an on-line chat room. Operators did more than just send messages back and forth; they had to call

up certain stations, ask for messages to be repeated, and verify the reception of messages. In countries where Morse's apparatus

was used, skilled operators quickly learned to read incoming messages by listening to the clicking of the apparatus, rather

than reading the dots and dashes marked on the paper tape, and this practice soon became the standard means of receiving.

It also encouraged more social interaction over the wires, and a new telegraphic jargon quickly emerged.

Rather than spell out every word ("PHILADELPHIA CALLING NEW YORK") letter by letter in laborious detail, conventions arose

by which telegraphers talked to each other over the wires using short abbreviations. There was no single standard: different

dialects or customs arose on different telegraph lines. However, one listing of common abbreviations compiled in 1859 includes

"1 1" (dot dot, dot dot) for "1 AM READY"; "G A" (dash dash dot, dot dash) for "GO AHEAD"-, "s F D" for "STOP FOR DINNER";

"G M" for "GOOD MORNING." This system enabled telegraphers to greet one another and handle most common situations as easily

as if they were in the same room. Numbers were also used as abbreviations: 1 meant "WAIT A MOMENT"; 2, "GET ANSWER IMMEDIATELY";

33, "ANSWER PAID HERE." All telegraph offices on a branch line shared one wire, so at any time there could be several telegraphers

listening in to wait for the line to become available. They could also chat, play chess, or tell jokes during quiet periods.

a

LTHOUGH THE TELEGRAPH, unlike later forms of electrical communication, did not require the consumer who was sending or receiving

a message to own any special equipment—or understand how to use it—it was still a source of confusion to those unfamiliar

with it. And just like the apocryphal story of the woman who tried to send her husband tomato soup by pouring it into the

telephone handset, there are numerous stories of telegraph-inspired confusion and misunderstanding.

One magazine article, "Strange Notions of the Telegraph," gives several examples of incomprehension: "One wiseacre imagined

that the wires were hollow, and that papers on which the communications were written were blown through them, like peas through

a pea shooter. Another decided that the wires were speaking tubes." And one man in Nebraska thought the telegraph wires were

a kind of tightrope; he watched the line carefully "to see the man run along the wires with the letter bags."

In one case a man came into a telegraph office in Maine, filled in a telegraph form, and asked for his message to be sent

immediately. The telegraph operator tapped it out in Morse to send it up the line and then spiked the form on the "sent" hook.

Seeing the paper on the hook, the man assumed that it had yet to be transmitted. After waiting a few minutes, he asked the

telegrapher, "Aren't you going to send that dispatch?" The operator explained that he already had. "No, you haven't," said

the man, "there it is now on the hook."