The Victorian Internet (9 page)

Read The Victorian Internet Online

Authors: Tom Standage

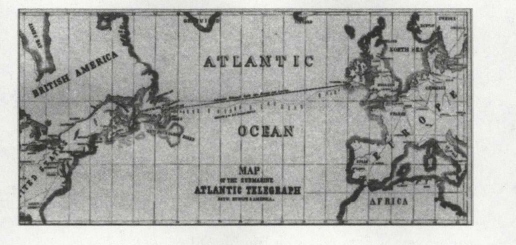

Morse's original telegraph line between Washington and Baltimore had hardly started out as a moneymaker; but the more points

there were on the network, the more useful it became. By the late 1860s, the telegraph industry, and the submarine cable business

in particular, was booming—and every investor wanted a piece of the action. "There can be no doubt that the most popular outlet

now for commercial enterprise is to be found in the construction of submarine lines of telegraph," reported the

Times

of London in 1869. By 1880, there were almost 100,000 miles of undersea telegraph cable.

Improvements in submarine telegraphy made it possible to run telegraph cables directly from Britain to out posts of the British

Empire, without having to rely on the goodwill of any other countries along the route, and "intra-imperial telegraphy" was

seen as an important means of centralizing control in London and protecting imperial traffic from prying eyes. The result

was a separate British network that interconnected with the global telegraph network at key points.

a

S THE NETWOTK connected more and more countries, the peaceful sentiments that had been expressed on the completion of the

Atlantic cable were extended to embrace the whole of humanity. The telegraph was increasingly hailed as nothing less than

the instrument of world peace.

"It brings the world together. It joins the sundered hemispheres. It unites distant nations, making them feel that they are

members of one great family," wrote Cyrus Field's brother Henry. "An ocean cable is not an iron chain, lying cold and dead

in the icy depths of the Atlantic. It is a living, fleshy bond between severed portions of the human family, along which pulses

of love and tenderness will run backward and forward forever. By such strong ties does it tend to bind the human race in unity,

peace and concord. . . . it seems as if this sea-nymph, rising out of the waves, was born to be the herald of peace."

Or, as another poetically inclined advocate of the telegraph's peacemaking powers put it: "The different nations and races

of men will stand, as it were, in the presence of one another. They will know one another better. They will act and react

upon each other. They may be moved by common sympathies and swayed by common interests. Thus the electric spark is the true

Promethean fire which is to kindle human hearts. Men then will learn that they are brethren, and that it is not less their

interest than their duty to cultivate goodwill and peace throughout the earth."

Unfortunately, the social impact of the global telegraph network did not turn out to be so straightforward. Better communication

does not necessarily lead to a wider understanding of other points of view; the potential of new technologies to change things

for the better is invariably overstated, while the ways in which they will make things worse are usually unforeseen.

Some simple yet secure cipher, easily acquired and easily read, should be introduced, by which means messages might to all

intents and purposes be "sealed" to any person except the recipient.

—QUARTERLY REVIEW,

1853

e

VER SINCE PEOPLE have invented things, other people have found ways to put those things to criminal use. "It is a well-known

fact that no other section of the population avail themselves more readily and speedily of the latest triumphs of science

than the criminal class," declared Inspector John Bonfield, a Chicago policeman, to the

Chicago Herald

in 1888. "The educated criminal skims the cream from every new invention, if he can make use of it." The telegraph was no

exception. It provided unscrupulous individuals with novel opportunities for fraud, theft, and deception.

In the days of the original optical telegraphs, Chappe's suggestion that the network be used to transmit stock market information

was originally rejected by Napoleon. However, by the 1830 it was being used for just that purpose, and before long, it was

being abused. Two bankers, Francois and Joseph Blanc, bribed the telegraph operators at a station near Tours, on the Paris-Bordeaux

line, to introduce deliberate but recognizable errors into the transmission of stock market information, to indicate whether

the stock market in Paris had gone up or down that day. By observing the arms of the telegraph from a safe distance as they

made what appeared to everyone else to be nothing more than occasional mistakes, the Blanc brothers could gain advance information

about the state of the market without the risk of being seen to be associating with their accomplices. This scheme operated

for two years before it was discovered in i836.

With the telegraph's ability to destroy distance, it provided plenty of scope for exploiting information imbalances: situations

where financial advantage can be gained in one place from exclusive ownership of privileged information that is widely known

in another place. A classic example is horse racing. The result of a race is known at the racetrack as soon as it is declared,

but before the invention of the telegraph, the information could take hours or even days to reach the bookmakers in other

parts of the country. Anyone in possession of the results of a horse race before the news reached the bookmakers could then

place a surefire bet on the winning horse. Almost immediately, rules were introduced to disallow the transmission of such

information by telegraph; but, as is often the case with attempts to regulate new technologies, the criminals tended to be

one step ahead of those making the rules.

One story from the 1840s tells of a man who went into the telegraph office at Shoreditch station in London on the day of the

Derby, an annual horse race, and explained that he had left his luggage and a shawl in the care of a friend at another station—the

station that just happened to be nearest the racetrack. He sent a perfectly innocent-sounding message asking his friend to

send the luggage and the shawl down to London on the next train, and the reply came back: "YOUR LUGGAGE AND TARTAN WILL BE

SAFE BY THE NEXT TRAIN." The apparently harmless reference to "TARTAN" revealed the colors of the winning horse and enabled

the man to place a bet and make a hefty profit.

Another attempt at such a ruse was, however, less successful. A man went into the Shoreditch telegraph office on the day of

a major horse race at Doncaster, at around the time of the race's end. He explained that he was expecting an important package

on the train from Doncaster, and that a friend had agreed to put the package in one of the first-class carriages. He asked

if he could telegraph his friend to find out the number of the carriage. However, the clerk saw through his scheme because

the carriages on that particular line—unlike the racehorses in that day's race—were not numbered. According to an account

in

Anecdotes

of the Telegraph,

when his request was questioned, the man ran off, "grinning a horrible, ghastly smile."

Both of these schemes used what was, in effect, a code, but a cleverly disguised one, since in the early days of the telegraph

the use of codes in telegrams was not allowed—except by governments and officials of the telegraph companies.

The Electric Telegraph Company, for instance, sent share prices from London to Edinburgh "by means of certain cabalistic signs"—in

other words, in code. Company officials consulted special codebooks to encode the prices in London, and decode them again

in Edinburgh, where they were posted on a board in a public room, to which bankers, merchants, and tradesmen could gain access

provided they paid a fee. In the early 1840s, before the telegraph network became widespread, this was a good arrangement

for all concerned; by transmitting the information over a distance of several hundred miles, the telegraph company was exploiting

another information imbalance, turning something that was common knowledge in London into a valuable commodity in Scotland.

Inevitably, an unscrupulous broker, hoping to do some exploiting of his own, tried to get hold of this valuable information

without paying for it. He invited two telegraph clerks to a pub and offered them a cut of any profits he made from share price

information passed to him. But when he failed to maintain his half of the bargain, they turned against him and exposed him

to the authorities.

This classic example shows that no matter how secure a code is, a person is always the weakest link in the chain. Even so,

there were continuous efforts to dream up un-crackable codes for use over the telegraph.

c

rYPTOGRAPHY—tinkering with codes and ciphers—was a common hobby among Victorian gentlemen. Wheatstone and his friend Charles

Bab-bage, who is best known for his failed attempts to build a mechanical computer, were both keen crackers of codes and ciphers—Victorian

hackers, in effect. "Deciphering is, in my opinion, one of the most fascinating of arts," Bab-bage wrote in his autobiography,

"and I fear I have wasted upon it more time than it deserves."

He and Wheatstone enjoyed unscrambling messages that appeared in code in newspaper classified advertisements—a popular way

for young lovers to communicate, since a newspaper could be brought into a house without arousing suspicion, unlike a letter

or a telegram. On one occasion Wheatstone cracked the cipher, or letter substitution code, used by an Oxford student to communicate

with his beloved in London. When the student inserted a message suggesting to the young woman that they run away together,

Wheatstone inserted a message of his own, also in cipher, advising her against it. The young woman in serted a desperate,

final message: "DEAR CHARLIE: WRITE NO MORE, OUR CIPHER IS DISCOVERED!" On another occasion Wheatstone cracked the code of

a seven-page letter written two hundred years earlier by Charles I entirely in numbers. He also devised a cunning form of

encryption, though it is generally known as Playfair's Cipher after his friend, Baron Lyon Playfair. Babbage too invented

several ciphers of his own.

And there was certainly a demand for codes and ciphers; telegrams were generally, though unfairly, regarded as less secure

than letters, since you never knew who might see them as they were transmitted, retransmitted, and retranscribed on their

way from sender to receiver. In fact, most telegraph clerks were scrupulously honest, but there was widespread concern over

privacy all the same.

"Means should be taken to obviate one great objection—at present felt with respect to sending private communications by telegraph—the

violation of all secrecy," complained the

Quarterly Review,

a British magazine, in 1853. "For in any case half a dozen people must be cognizant of every word addressed by one person

to another. The clerks of the [telegraph companies] are sworn to secrecy, but we often write things that it would be intolerable

to see strangers read before our eyes. This is a grievous fault in the telegraph, and it must be remedied by some means or

other." The obvious solution was to use a code.

Meanwhile, the rules determining when codes could and could not be used were becoming increasingly complicated as national

networks, often with different sets of rules, were interconnected. Most European countries, for example, forbade the use of

codes except by governments, and in Prussia there was even a rule that copies of all messages had to be kept by the telegraph

company. There were also various rules about which languages telegrams could be sent in; any unapproved language was regarded

as a code.

The confusion of different rules increased as more countries signed bilateral connection treaties. Finally, in 1864, the French

government decided it was time to sort out the regulatory mess. The major countries of Europe were invited to a conference

in Paris to agree on a set of rules for international telegraphy. Twenty states sent delegates, and in 1865 the International

Telegraph Union was born. The rules banning the use of codes by anyone other than governments were scrapped; at last, people

could legally send telegrams in code. Not surprisingly, they started doing so almost immediately.

I

n THE UNITED STATES, where the telegraph network was controlled by private companies rather than governments, there were

no rules banning the use of codes, so they were adopted much earlier. In fact, the first known public codes for the electric

telegraph date back to 1845, when two codebooks were published to provide businesses with a means of communicating secretly

using the new technology.

That year, Francis 0. J. Smith, a congressman and lawyer who was one of Morse's early backers, published

The Secret Corresponding Vocabulary Adapted for Use to

Morse's Electro-Magnetic Telegraph.

At around the same time, Henry J. Rogers published a

Telegraph Dictionary Arranged

for Secret Correspondence Through Morse's Electro-Magnetic

Telegraph.

Both codes consisted of nothing more than a numbered dictionary of words (A1645, for example, meant "alone" in Smith's vocabulary,

which consisted of 50,000 such substitutions), but since numbers were frequently garbled in transmission—telegraph clerks

were used to transmitting recognizable words, not meaningless strings of figures—devisers of codes soon switched to the use

of code words to signify other words or even entire phrases. Ry 1854, one in eight telegrams between New York and New Orleans

was sent in code. The use of the telegraph to send bad news in an emergency is well illustrated by one code, which used single

Latin words to represent various calamities:

COQUABUM

meant "ENGAGEMENT BROKEN OFF,"

CAMBITAS

meant "COLLARBONE PUT OUT," and

GNAPHALIO

meant "PLEASE SEND A SUPPLY OF LIGHT CLOTHING."

Of course, such codes weren't all that secret because the codebooks were widely available to everyone (though in some cases

they could be customized). But before long another advantage of using such nonsecret codes, known as "commercial" codes, soon

became clear—to save money. By using a code that replaced several words with a single word, telegrams cost less to send.

Those for whom security rather than economy was paramount preferred to use ciphers, which take longer to encode and decode

(since individual letters rather than whole words are substituted) but are harder to crack. Yet while such codes and ciphers

were a boon for users, they were extremely inconvenient for telegraph companies. Codes reduced their revenue, since fewer

words were transmitted, and ciphers made life harder for operators, who found it more difficult to read and transmit gibberish

than messages in everyday language.

The increased difficulty of transmitting gibberish was recognized by the International Telegraph Union (ITU), so when new

rules were drawn up concerning the use of codes and ciphers, the convention was adopted that messages in code would be treated

just like messages in plain text, provided they used pronounceable words to stand for complex phrases, and that no word was

more than seven syllables long. Messages in cipher (defined as those consisting of gibberish words), on the other hand, were

charged on the basis that every five characters counted as one word. Since the average length of a word in a telegram was

more than five letters, this effectively meant that messages in cipher were charged at a higher rate.

During the 1870s, demand for codes was further fueled by the growth in submarine telegraphy, which allowed messages to be

sent to distant lands—for a price. The ABC Code, compiled by William Clausen-Thue, a shipping manager, was the first commercial

code to sell in really large quantities. It had a vast vocabulary that represented many common phrases using a single word,

which was a particular advantage when sending intercontinental telegrams, since they were extremely expensive. (The original

rate for transatlantic telegrams was £20—then about $100—for a minimum of ten words. The cable actually became more profitable

when the rate was halved and then halved again, because the lower prices attracted more customers.) On long cables where

90 percent of messages were business related, typically 95 percent were in code.

With codes in such common use, many companies chose to develop their own codes for private use with their own correspondents

overseas, either because they wanted additional security or because existing codes failed to meet the vocabulary needs of

those in specialized fields. Detwil-ler & Street, a fireworks manufacturer, for example, devised its own code in which the

word "FESTIVAL" meant "A CASE OF THREE MAMMOTH TORPEDOES." In India, the Department of Agriculture had a special code that

dealt specifically with weather and famine, in which the word "ENVELOPE" meant "GREAT SWARMS OF LOCUSTS HAVE APPEARED AND

RAVAGED THE CROPS." The fishing industry, the mining industry, the sausage industry, bankers, railroads, and insurance companies

all had their own codes, often running into hundreds of pages, to detail incredibly specific phrases and situations.