The Warlord of the Air (13 page)

Read The Warlord of the Air Online

Authors: Michael Moorcock

“What’s all this about, Muir?” I asked.

Muir shook his head. “As far as I can tell, this gentleman,” he indicated the civil servant, “asked if he could borrow the salt from Mr. Reagan’s table. Mr. Reagan hit him, sir, then started on this gentleman’s friends...”

I saw now that there was a livid mark on the Indian’s forehead.

I pulled myself together as best I could and called out: “All right, everybody. Let him go. Could you please stand back? Stand back, please.”

Gratefully, the passengers and crew members moved away from Reagan, who stood panting and glaring and plainly out of his mind. With a sudden movement he leapt onto a nearby table, hunched with his stick at the ready.

I tried to speak civilly, remembering that it was my duty to protect both the good name of the shipping company, to protect the name of my own service and to give Mr. Reagan no opportunity to sue anyone or use his political connections to harm anyone. It was hard to remember all this, particularly when I hated the man so much. I did my best to feel sorry for him, to humour him. “It’s over now, Captain Reagan. If you will apologize to the gentleman you struck—”

“Apologize? To that scum!” With a snarl, Reagan aimed a blow at me with his pole. I grabbed it and dragged him off the table. If I had struck him then, in order to calm him down, I might have been forgiven. But it was as if his own madness was infectious.

Reagan put his snarling face up against mine and growled: “Give me my stick, you damned nigger-loving British sissy!”

It was too much for me.

I don’t actually remember striking the first blow. I remember punching and punching and being pulled back. I remember seeing his blood flowing from his cut face. I remember shrieking something about what he had done to the skipper. I remember his pole clutched in my hands rising and falling and then I was being pulled back by several ratings and everything became suddenly, terrifyingly calm and Reagan lay on the floor, bruised and bloody and completely insensible, perhaps dead.

I turned, dazed, and saw the shocked faces of the scouts, the passengers, the crew.

I saw the second officer, now in command, come running up. I saw him look down at Reagan’s body and say “Is he dead?”

“He should be,” said someone. “But he isn’t.”

The second officer came up to me and there was pity in his face. “You poor devil, Bastable,” he said. “You shouldn’t have done it, old man. You’re in trouble now, I’m afraid.”

O

f course, I was suspended from duty as soon as I got to Sydney and reported to the local S.A.P. headquarters. Nobody was unsympathetic, especially when they had heard the full story from the other officers of the

Loch Etive.

But Reagan had already given

his

story to the evening papers. The worst was happening.

AMERICAN TOURIST ATTACKED BY POLICE OFFICER

, said the

Sydney Herald,

and most of the reports were of the sensational kind and most of them were on the front page. The company and the name of the ship were mentioned; His Majesty’s most recently formed service, the Special Air Police, were mentioned (“Is this what we may expect from those commissioned to protect us?” asked one paper). Passengers had been interviewed and a non-committal statement from the company’s Sydney office was quoted. I had said nothing to the Press, of course, and some of the newspapers had taken this as an admission that I had set upon Reagan without provocation and tried to kill him. Then I received a cable from my C.O. in London. return at once.

Depression filled my mind and set there, hard and cold, and I could think nothing but black thoughts on the journey back to London in the aerial man-o’-war

Relentless.

There was no possible excuse, as far as the army was concerned, for my behaviour. I knew I would be court-martialed and almost certainly cashiered. It was not a pleasant prospect.

When I arrived in London I was taken immediately to the S.A.P. headquarters near the small military airpark at Limehouse. I was confined to barracks, pending a decision from my C.O. and the War Office as to what to do with me.

As it emerged, Reagan was persuaded to drop his charges against everyone and was further persuaded to admit that he had seriously provoked me, but I had still behaved badly and a court-martial was still in order.

Several days after hearing about Reagan’s decision, I was summoned to the C.O.’s office and asked to sit down. Major-General Nye was a decent type and very much of the old school. He understood what had happened but put his position bluntly:

“Look here, Bastable, I know what you’ve been through. First the amnesia and now this—well, this fit of yours, if you like. Fit of rage, what? I know. But you see we can’t be sure you won’t have another. I mean—well, the old brain-box and all that—a trifle shaky, um?”

I smiled wryly at him, I remember. “You think I’m mad, sir?”

“No, no, no, of course not. Nervy, say. Anyway, the long and the short of it is this, Bastable: I want your resignation.”

He coughed with embarrassment and offered me a cigar without looking at me. I refused.

Then I stood up and saluted. “I understand perfectly, sir, and I appreciate why you want to do it this way. It’s decent of you, sir. Of course, you shall have my resignation from the service. Morning all right, sir?”

“Fine. Take your time. Sorry to lose you. Good luck, Bastable. I gather you needn’t worry about Macaphees taking any action. Captain Quelch spoke up for you with the owners. So did the rest of the officers, I gather.”

“Thank you for letting me know, sir.”

“Not at all. Cheerio, Bastable.” He got up and shook my hand. “Oh, by the way, your brother wants to see you. I got a message. He’ll meet you at the Royal Aeronautical Club this evening.”

“My brother, sir?”

“Didn’t you know you had one?”

I did have a brother. In fact I had three. But I had left them behind in 1902.

Feeling as if I had gone completely mad I left the C.O.’s office, went back to my quarters, composed my letter of resignation, packed my few things into a bag, changed into civilian clothes and took an electric hansom to Piccadilly and the Royal Aeronautical Club.

Why should someone claim to be my brother? There was probably a simple explanation. A mistake, of course, but I could not be sure.

A Bohemian “Brother”

A

s I sat back in the smoothly moving cab, I stared out of the windows and tried to collect my thoughts. Since the incident with Reagan I had been stunned and only now that I had left my barracks behind me was I beginning to realize the implications of my action. I also realized that I had got off rather lightly, all things considered. Yet my efforts to become accepted by the society of 1974 had, it now appeared, been completely wasted. I was much more of an outsider than when I had first arrived. I had disgraced my uniform and put myself beyond the pale.

What was more, the euphoric dream had begun to turn into a crazy nightmare. I took out my watch. It was only three o’clock in the afternoon. Not evening by anyone’s standards. I was uncertain as to what kind of reception I might have at the R.A.C. I was, of course, a member, but it was quite possible they would wish me to resign, as I had resigned from the S.A.P. I couldn’t blame anyone for wishing this. After all, I was likely to embarrass the other members. I would leave my visit until the last possible moment. I tapped on the roof and told the cabbie to stop at the nearest pedestrian ingress, then I got out of the cab, paid my fare and began to wander listlessly around the arcades beneath the graceful columns supporting the traffic levels. I stared at the profusion of exotic goods displayed in the shop windows; goods brought from all corners of the Empire, reminding me of places I might never see again. Searching for escape I went into a kinema and watched a musical comedy set in the sixteenth century and featuring an American actor called Humphrey Bogart playing Sir Francis Drake and a Swedish actress (Bogart’s wife, I believe) called Greta Garbo as Queen Elizabeth. Oddly, it is one of the clearest impressions I have of that day.

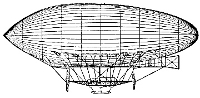

At about seven o’clock I turned up at the club and slipped unnoticed into the pleasant gloom of the bar, decorated with dozens of airship mementos. There were a few chaps chatting at tables but luckily nobody recognized me. I ordered a whisky-and-soda and drank it down rather quickly. I had had several more by the time someone touched me on the arm and I turned suddenly, fully expecting to be asked to leave.

Instead I was confronted by the cheerful grin on the face of a young man dressed in what I had learned was the fashion amongst the wilder undergraduates at Oxford. His black hair was worn rather long and brushed back without a parting. He wore what was virtually a frock coat, with velvet lapels, a crimson cravat, a brocade waistcoat and trousers cut tightly to the knee and then allowed to flare at the bottoms. We should have recognized it in 1902 as being very similar to the dress affected by the so-called aesthetes. It was deliberately Bohemian and dandified and I regarded people who wore this ‘uniform’ with some suspicion. They were not my sort at all. Where I had escaped notice, this young man had the disapproving gaze of all. I was acutely embarrassed.

He seemed unaware of the reaction he had created in the club. He took my limp hand and shook it warmly. “You’re brother Oswald, aren’t you?”

“I’m Oswald Bastable,” I agreed. “But I don’t think I’m the one you want. I have no brother.”

He put his head on one side and smiled. “How d’you know, eh? I mean, you’re suffering from amnesia, aren’t you?”

“Well, yes...” It was perfectly true that I could hardly claim to have lost my memory and then deny that I had a brother. I had placed myself in an ironic situation. “Why didn’t you come forward earlier?” I countered. “When there was all that stuff about me in the newspapers?”

He rubbed his jaw and eyed me sardonically. “I was abroad at the time,” he said. “In China, actually. Bit cut off there.”

“Look here,” I said impatiently, “you know damn’ well you’re not my brother. I don’t know what you want, but I’d rather you left me alone.”

He grinned again. “You’re quite right. I’m not your brother. The name’s Dempsey actually—Cornelius Dempsey. I thought I’d say I was your brother in order to pique your curiosity and make sure you met me. Still,” he gave me that sardonic look again, “it’s funny you should be suffering from total amnesia and yet know that you haven’t got a brother. Do you want to stay and chat here or go and have a drink somewhere else?”

“I’m not sure I want to do either, Mr. Dempsey. After all, you haven’t explained why you chose to deceive me in this way. It would have been a cruel trick, if I had believed you.”

“I suppose so,” he said casually. “On the other hand you might have a good reason for

claiming

amnesia. Maybe you’ve something to hide? Is that why you didn’t reveal your real identity to the authorities?”

“What I have to hide is my own affair. And I can assure you, Mr. Dempsey, that Oswald Bastable is the only name I have ever owned. Now—I’d be grateful if you would leave me alone. I have plenty of other problems to consider.”

“But that’s why I’m here, Bastable, old chap. To help you solve those problems. I’m sorry if I’ve offended you. I really did come to help. Give me half-an-hour.” He glanced around him. “There’s a place round the corner where we can have a drink.”

I sighed. “Very well.” I had nothing to lose, after all. I wondered for a moment if this dandified young man, so cool and self-possessed, actually knew what had really happened to me. But I dismissed the idea.

We left the R.A.C. and turned into the Burlington Arcade, which was one of the few places which had not changed much since 1902, and stepped into Jermyn Street. At last Cornelius Dempsey stopped at a plain door and rapped several times with the brass knocker until someone answered. An old woman peered out at us, recognized Dempsey, and admitted us to a dark hallway. From somewhere below came the sound of voices and laughter and, by the smell, I judged the place to be a drinking club of some kind. We went down some stairs and entered a poorly lit room in which were set out a number of plain tables. At the tables sat young men and women dressed in the same Bohemian fashion as Dempsey. One or two of them greeted him as we made our way among the tables and sat down in a niche. A waiter came up at once and Dempsey ordered a bottle of red Vin Ordinaire. I felt extremely uncomfortable, but not as badly as I had felt at my own club. This was my first glimpse of a side of London life I had hardly realized existed. When the wine came I drank down a large glass. If I were to be an outcast, I thought bitterly, then I had best get used to this kind of place.

Dempsey watched me drink, a look of secret amusement on his face. “Never been to a cellar club before, eh?”

“No.” I poured myself another drink from the bottle.

“You can relax here. The atmosphere’s pretty free and easy. Wine all right?”

“Fine.” I sat back in my chair and tried to appear confident. “Now what’s all this about, Mr. Dempsey?”

“You’re out of work at the moment, I take it?”