The Warlord of the Air (14 page)

Read The Warlord of the Air Online

Authors: Michael Moorcock

“That’s an understatement. I’m probably unemployable.”

“Well, that’s just it. I happen to know there’s a job going if you want one. On an airship. I’ve already talked to the master and he’s willing to take you on. He knows your story.”

I became suspicious. “What sort of a job, Mr. Dempsey? No decent skipper would...”

“This skipper is one of the most decent men ever to command a ship.” He dropped his bantering manner and spoke seriously. “I admire him tremendously and I know you’d like him. He’s straight as a die.”

“Then why—?”

“His ship is a bit of a crate. Not one of your big liners or anything like that. It’s old-fashioned and slow and carries cargo mainly. Cargo that other people aren’t interested in. Small jobs. Sometimes dangerous jobs. You know the kind of ship.”

“I’ve seen them.” I sipped my wine. The chance was the only sort I might expect and I was incredibly lucky to get it. It was logical that small ‘tramp’ airships should be short of trained airshipmen when the rewards for working for the big ships were so much greater. And yet, at that moment, I hardly cared. I was still full of bitterness at my own foolishness. “But are you sure the captain knows the whole story? I was chucked out of the army for good reason, you know.”

“I know the reason,” said Dempsey earnestly. “And I approve of it.”

“Approve? Why?”

“Just say I don’t like Reagan’s type. And I admire what you did for those Indians he attacked. It proves you’re a decent type with your heart in the right place.”

I’m not sure I appreciated such praise from that young man. I shrugged. “Defending the Indians was only incidental,” I told him. “I hated Reagan, because of what he did to my skipper.”

Dempsey smiled. “Put it how you like, Bastable. Anyway, the job’s going. Want it?”

I finished my second glass of wine and frowned. “I’m not sure...”

Dempsey poured me another glass. “I’m not trying to persuade you to do something you don’t want to—but I might point out that few people will want to employ you as anything more than a deckhand—for a while, at least.”

“I’m aware of that.”

Dempsey lit a long cheroot. “Perhaps you have friends who’ve offered you a ground job?”

“Friends? No. I’ve no friends.” It was true. Captain Quelch had been the nearest thing I had had to a friend.

“And you’ve experience of airships. You could handle one if you had to?”

“I suppose so. I passed an exam equivalent to a second officer’s. I’m probably a bit weak on the practical side.”

‘You’ll soon learn that, though.”

“How do you happen to know the captain of an air freighter?” I asked. “Aren’t you a student?”

Dempsey lowered his eyes. “You mean an undergraduate? Well, I was. But that’s another story altogether. I’ve followed your career, you know, since you were found on that mountain top. You captured my imagination, you might say.”

I laughed then, without much humour. “Well, I suppose it’s generous of you to try to help me. When can I see this captain of yours?”

“Tonight?” Dempsey grinned eagerly. “We could go down to Croydon in my car. What do you say?”

I shrugged. “Why not?”

Captain Korzeniowski

D

empsey drove down to Croydon at some speed but I was forced to admire the way he controlled the old-fashioned Morgan steamer. We reached Croydon in half-an-hour.

The town of Croydon is an airpark town. It owes its existence to the airpark and everywhere you look there are reminders of the fact. Many of the hotels are named after famous airships and the streets are crowded with flyers of every nationality. It is a brash, noisy town compared with most and must be quite similar to some of the old seaports of my own age (perhaps I should use the future tense for all this and say ‘will be’ and so on, but I find it hard to do, for all these events took place, of course, in my personal past).

Dempsey drove us into the forecourt of a small hotel in one of the Croydon backstreets. The hotel was called

The Airman’s Rest

and had evidently been a coaching inn in earlier days. It was, needless to say, in the old part of the town and contrasted rather markedly with the bright stone and glass towers which dominated most of Croydon.

Dempsey took me through the main parlour full of flyers of the senior generation who plainly preferred the atmosphere of

The Airman’s Rest

to that of the more salubrious hotels. We went up a flight of wooden stairs and along a passage until we came to a door at the end. Dempsey knocked.

“Captain? Are you receiving visitors, sir?”

I was surprised at the genuine tone of respect with which the young man addressed the unseen captain.

“Enter.” The voice was harsh and guttural. A foreign voice.

We walked into a comfortable bed-sitting room. A fire blazed in the grate, providing the only illumination. In a deep leather armchair sat a man of about sixty. He had an iron-grey beard cut in the Imperial style and hair to match. His eyes were blue-grey and their gaze was steady, penetrating, totally trustworthy. He had a great beak of a nose and a strong mouth. When he stood up he was relatively short but powerfully built. His handshake was dry and firm as Dempsey introduced us.

“Captain Korzeniowski, this is Lieutenant Bastable.”

“How do you do, lieutenant.” The accent was thick but the words were clear. “Delighted to meet you.”

“How do you do, sir. I think you’d better refer to me as plain ‘mister’. I resigned from the S.A.P. today. I’m a civilian now.”

Korzeniowski smiled and turned towards a heavy oak sideboard. “Would you care for a drink

—Mister

Bastable?”

“Thank you, sir. A whisky?”

“Good. And you, young Dempsey?”

“A glass of that Chablis I see, if you please, captain.”

“Good.”

Korzeniowski was dressed in a heavy white roll-neck pullover. His trousers were the midnight blue of a civil flying officer. Over a chair near the desk, against the far wall I saw his jacket with its captain’s rings, and on top of that his rather battered cap.

“I put the proposal to Mr. Bastable, sir,” said Dempsey as he accepted his glass. “And that’s why we’re here.”

Korzeniowski fingered his lips and looked thoughtfully at me. “Doubtless,” he murmured. “Doubtless.” After giving us our drinks he went back to the sideboard and poured himself a modest whisky, filling the glass up with soda. “You know I need a second officer pretty badly. I could do with a man with rather more experience of flying, but I can’t get anyone in England and I don’t want the type of man I’d be likely to find out of England. I’ve read about you. You’re hot-tempered, eh?”

I shook my head. Suddenly it seemed to me that I wanted very much to serve with Captain Korzeniowski for I had taken an instant liking to the man. “Not normally, sir. These were—well, special circumstances, sir.”

“That’s what I gathered. I had a fine second officer until recently. Chap named Marlowe. Got into some trouble in Macao.” The captain frowned and took a cheroot case from his desk. He offered me one of the hard, black sticks of tobacco and I accepted. Dempsey refused with a grin. As he spoke, Captain Korzeniowski kept his eyes on me and I felt he was reading my soul. He spoke rather ponderously and all his actions were slow, calculated. “You were found in the Himalayas. Lost your memory. Trained for the air police. Got into a fight with a passenger on the

Loch Etive.

Lost your temper. Hurt him badly. Passenger was a bore, eh?”

“Yes, sir.” The cheeroot was surprisingly mild and sweetsmelling.

“Objected to eating with some Indians, I gather?”

“Among other things, sir.”

“Good.” Korzeniowski gave me another of his sharp, penetrating glances.

“Reagan was responsible, sir, for our skipper’s breaking his leg. It meant that the old man would be grounded for good. The skipper couldn’t bear that idea, sir.”

Korzeniowski nodded. “Know how he feels. Captain Quelch. Used to know him. Fine airshipman. So your crime was an excess of loyalty, mm? That

can

be a pretty serious crime in some circumstances, eh?”

His words seemed to have an extra significance I couldn’t quite divine. “I suppose so, sir.”

“Good.”

Dempsey said, “I think, sir, that temperamentally at any rate he’s one of us.”

Korzeniowski raised his hand to silence the young man. The captain was staring into the fire, deep in consideration of something. A few moments later he turned round and said, “I am a Pole, Mr. Bastable. A naturalized Briton, but a Pole by birth. If I went back to my homeland, I would be shot. Do you know why?”

“No, sir.”

The captain smiled and spread his hands. “Because I am a Pole. That is why.”

“You are an exile, sir? The Russians...?”

“Exactly. The Russians. Poland is part of their Empire. I felt that this was wrong, that nations should be free to decide their own destinies. I said so—many years ago. I was heard to say so. And I was exiled. That was when I joined the British Merchant Air Service. Because I was a Polish patriot.” He shrugged. I wondered why he was telling me this, but I felt there must be a point to it, so I listened respectfully. Finally he looked up at me. “So you see, Mr. Bastable, we are both outcasts, in our way. Not because we wish it, but because we have no choice.”

“I see, sir.” I was still puzzled, but said no more.

“I own my ship,” said Korzeniowski. “She isn’t much to look at, but she’s a good little craft. Will you join her, Mr. Bastable?”

“I would like to sir, I’m very grateful...”

“You’ve no need to be grateful, Mr. Bastable. I need a second officer and you need a position. The pay isn’t very high. Five pounds a month, all found.”

“Thank you, sir.”

“Good.”

I still wondered what connection there could possibly be between the young Bohemian and the old airship skipper. They seemed to know each other quite well.

“I think you’ll be able to find accommodation for the night in this hotel, if it suits you,” Captain Korzeniowski continued. “Join the ship tomorrow. Eight o’clock be all right?”

“Fine, sir.”

“Good.”

I picked up my bag and looked expectantly at Dempsey. The young man glanced at the captain, grinned at me and patted me on the arm. “Get yourself settled in here. I’ll join you later. One or two things to discuss with the captain.” Still in something of a daze I said goodbye to my new skipper and left the room. As I closed the door I heard Dempsey say, “Now, about the passengers, sir...”

N

ext morning I took an omnibus to the airpark.

There were dozens of airships moored there, coming and going like monstrous bees around a monstrous hive. In the autumn sunshine the hulls of the vessels shone like silver or gold or alabaster. Before he had left the previous night Dempsey had given me the name of the ship I was to join. She was called

The Rover

(a rather romantic name, I thought) and the airpark authorities had told me she was moored to Number 14 mast. In the cold light of day I was beginning to wonder if I had not accepted the position rather hastily but it was too late for second thoughts. I could always leave the ship later if I found that I wasn’t up to what was expected of me.

When I got to Number 14 mast I found that she had been shifted to make room for a big Russian freighter with a combustible cargo which had to be taken off in a hurry. Nobody seemed to know where

The Rover

was now moored.

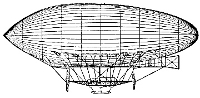

Eventually, after half-an-hour of fruitless wandering about, I was told to go to Number 38 mast, right on the other side of the park. I trudged beneath the huge hulls of liners and cargo ships, dodging between the shivering mooring cables, circumnavigating the steel girders of the masts, until at last I saw Number 38 and my new craft.

She was battered and she needed painting, but she was as brightly clean as the finest liner. She had a hard hull, obviously converted from a soft, fabric cover of the old type. She was swaying a little at her mast and seemed, by the way she moved in her cables, very heavily loaded. Her four big, old-fashioned engines were housed in outside nacelles which had to be reached by means of partly covered catwalks, and her inspection walks were completely open to the elements. I felt like someone who had been transferred from the

Oceanic

to take up a position on a tramp steamer. For all that I came from a period of time before any airship had seemed a practical means of travel, my interest in

The Rover

was almost one of historical curiosity as I looked her over. She was certainly weather-beaten. The silvering on her hull was beginning to flake and the lettering of her number (806), name and registration (London) had peeled off in places. Since it was illegal to have even a partially obliterated registration, there were a couple of airshipmen hanging in a pulley platform suspended from the topside catwalk, touching up the transfers with black creosote. She was even older than my first ship, the

Loch Ness,

and much more primitive, with a slightly piratical look about her. I doubted she boasted such things as computers, temperature regulators or anything but the most unsophisticated form of wireless telephone, and her speed could not have been much over eighty miles an hour.