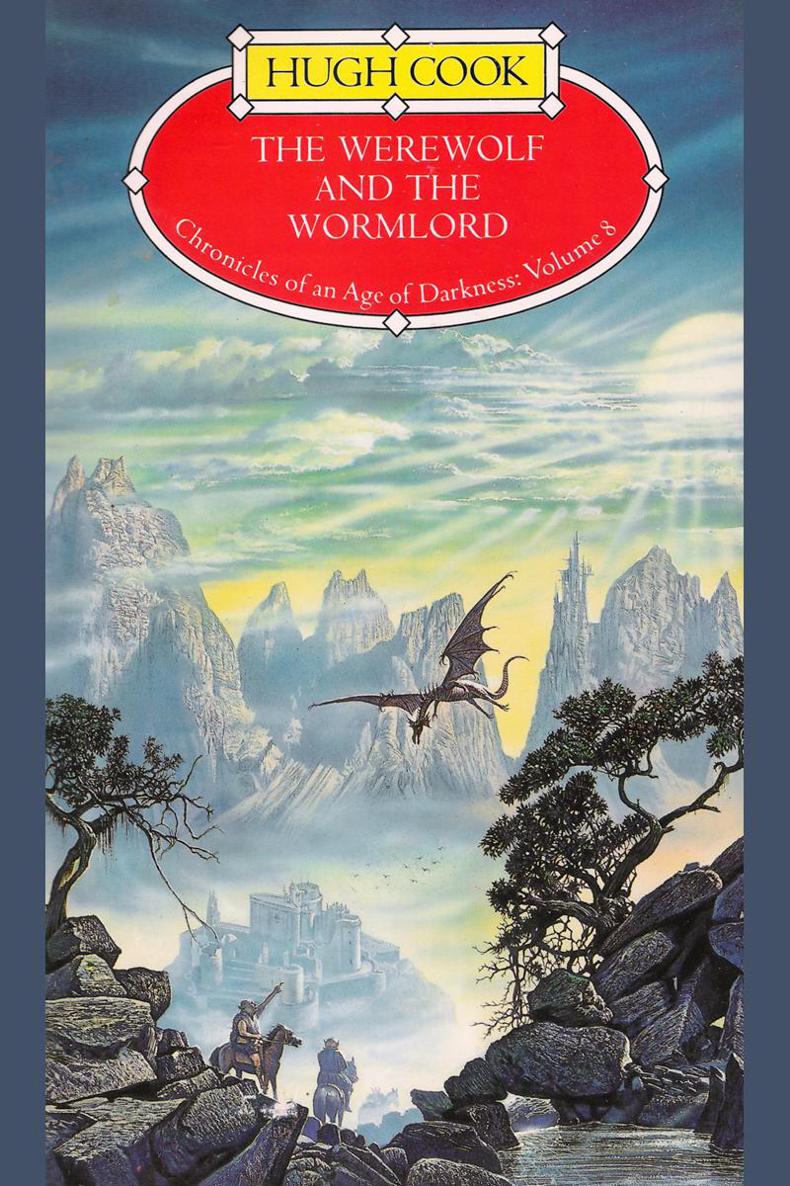

The Werewolf and the Wormlord

Read The Werewolf and the Wormlord Online

Authors: Hugh Cook

Alfric turned. The man who had stalked unheard to well within killing distance was Nappy, a huffy-puffy individual of slightly less than average height. Nappy was pink of face and bald of pate and could often be seen hustling about Galsh Ebrek looking slightly comical thanks to his pigeon-toed gait. He was renowned for his sweet temper, for the jolly delight he took in all innocent pleasures, and for his work as a committee man. Nappy was famous in charity circles, and was known to be happiest at festivals when he could transmogrify himself into Mister Cornucopia, and dispense sweets for the children and kisses for the blushing virgins.

‘I’m so glad to see you, Mister Danbrog,’ said Nappy, extending his hand. Alfric took it and pumped it. Nappy’s hand was soft and damp. A clinging, friendly hand.

‘We haven’t seen you here for ever so long,’ said Nappy. ‘I’m so, so very glad to see you.’

The sincerity of these effusions could not be doubted. That was Nappy all over. He was acknowledged as the happiest, friendliest person in Wen Endex. Which made no difference to the facts of the matter. Nappy was what he was and he did what he did, and there was no getting round that.

‘Sorry I can’t stay to chat,’ said Nappy, shifting on his feet in that fluidly furtive manner which was his trademark, ‘but I must be going now.’

And already Nappy was sliding, sidestepping, nim-bling past Alfric’s defenses. Alfric thought him shifting right, but he was gone to the left, sliding past and—

And—

And?

Alfric wanted to scream.

Nappy was behind him.

And all Alfric could think was this:

‘Just let it be quick, that’s all. Just let it be quick.’

Also by Hugh Cook

THE WIZARDS AND THE WARRIORS

THE WORDSMITHS AND THE WARGUILD

THE WOMEN AND THE WARLORDS

THE WALRUS AND THE WARWOLF

THE WICKED AND THE WITLESS

THE WISHSTONE AND THE WONDERWORKERS

THE WAZIR AND THE WITCH

and published by Corgi Books

THE WEREWOLF AND THE WORMLORD

A CORGI BOOK 0552135380

First publication in Great Britain

PRINTING HISTORY Corgi edition published 1991

Copyright © Hugh Cook 1991

The right of Hugh Cook to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Conditions of sale

1.This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade

or otherwise,

be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published

and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

2.

This book is sold subject to the Standard Conditions of Sale of Net Books and may not be re-sold in the UK below the net price fixed by the publishers for the book.

This book is set in 10/12 pt Times by County Typesetters, Margate, Kent

Corgi Books are published by Transworld Publishers Ltd., 61-63 Uxbridge Road, Ealing, London W5 5SA, in Australia by Transworld Publishers (Australia) Pty. Ltd., 15-23 Helles Avenue, Moorebank, NSW 2170, and in New Zealand by Transworld Publishers (N.Z.) Ltd., Cnr. Moselle and Waipareira Avenues, Henderson, Auckland.

Made and printed in Great Britain by

BPCC Hazell Books

Aylesbury, Bucks., England

Member of BPCC Ltd

Table of Contents

CHAPTER ONE

Touching that monstrous bulk of the whale or ork we have received nothing certain. They grow exceedingly fat, insomuch that an incredible quantity of oil will be extracted out of one whale.

Lord Baakan,

History of Life and Death

It is an undisputed truth that a man with weak sight must be in need of an ogre; for, as all the world knows, ogres are by far the best oculists. Therefore it is not surprising that, on each of his annual visits to the Qinjoks, Alfric Danbrog took the opportunity to have his eyes retested and to get a new pair of spectacles ground to his prescription.

Shortly after his thirty-third birthday, Alfric made his fifth such venture into the mountains. On this occasion, the bespectacled banker took with him a large carven box. This was a gift for the ogre king; and inside there were twenty pink mice, five thousand dead fleas, thirty chunks of cheese and seven dragons.

Alfric’s journey to the Qinjoks was made exclusively by night, which multiplied its many difficulties. However, young Danbrog was not just a banker but the son of a Yudonic Knight, and he pressed on regardless of danger. Once the many difficulties of the journey had been overcome, Alfric’s first duty was to present himself to the ogre king. The audience took place in a deep delved mountain cave in one of the shallower portions of that underground redoubt known as the Qinjok Sko.

Before the meeting, the king’s chamberlain cautioned Alfric thus:

‘You will not address the king by his given name.’

The chamberlain, a small and nervous troll, had given Alfric exactly the same warning on each of the four previous visits the young banker had made to these mountains. But Alfric did not remind him of this.

‘My lord,’ said Alfric, ‘I do not even know the king’s name, therefore am in no danger of addressing him thereby.’

This was a diplomatic mistruth. Alfric Danbrog knew full well that the ogre king had been named Sweet Sugar-Delicious Dimple-Dumpling.

Among ogres, the naming of children is traditionally a mother’s privilege; and female ogres are apt to lapse into a disgustingly mawkish sentimentality shortly after giving birth. Those who cleave to the evolutionary heresy hold that such a lapse is necessary to the survival of the species, for baby ogres (and the full-grown adults, come to that) are so hideously ugly that it is surely only the onset of such sentimentality which keeps their mothers from strangling them at birth.

Once the chamberlain had been assured on this point of protocol, Alfric was admitted to the presence of the above-mentioned Sweet Sugar-Delicious Dimple-Dumpling, king of the Qinjoks. The king, let it be noted, was nothing like his name. Rather, he would have better fitted the name his father would have liked to bestow on him: Bloodgut the Skullsmasher.

While the ogre and the banker met on cordial terms, there stood between them a line of granitic cubes, each standing taller than a cat but shorter than a hunting hound. These were stumbling blocks, placed there in case Alfric should take it into his head to draw his sword and charge the throne.

Technically, there was peace between Galsh Ebrek and the Qinjoks. Furthermore, every expert in combat will tell you that it is theoretically impossible for a lone swordsman to overcome a full-grown ogre. However, the Yudonic Knights are what they are; and the king did well to be cautious.

‘We trust your journey was pleasant,’ said King Dimple-Dumpling.

‘It was not,’ said Alfric. ‘The roads between Galsh Ebrek and the Qinjoks owe more to fantasy than to fact. The dark was dark, the rain was wet, and the mud was excessive in the extreme, quantity in this case quite failing to make up for lack of quality.’

So he spoke because his ethnology texts had taught him that ogres value honesty in speech above all other things.

Such scholarly claims are in fact exaggerated. There are many things an orgre values far more, some of them being mulberry wine, gluttonous indulgence in live frogs, and the possession of vast quantities of gold.

‘So,’ said the ogre king. ‘You travelled by night.’

‘I did, my liege,’ said Alfric.

‘Hmmm,’ said the ogre king.

While the king puzzled over this strange behaviour, Alfric had ample time to study his majesty’s surrounds. Ranged behind the king were racks of skulls; interlaced washing lines strung with scalps; and two vultures, each a triumph of the taxidermist’s art. Carven draconites served these beasts as eyes, and an evil light swashed from these gems as they caught the buckling flaze of torches. Flanking these beasts were skeletons in duplicate; while at the king’s head was the mouldering head of a dragon. And, in pride of place at his right hand, a low bookcase crammed with philosophy books.

Alfric started to sweat.

Not because he was frightened, but because the cave was grossly overheated.

‘So,’ said the king. ‘You travelled by night. Which means, does it not, that She walks again?’

‘So it has been said,’ acknowledged Alfric.

‘It has been said, has it? And what do you believe?’ ‘That custom commands me,’ said Alfric. ‘Hence I walk by night. I can do no less. I am of a Family.’

‘You belong to the Bank,’ said the king, ‘yet declare allegiance to a Family.’

‘The Bank, my liege, lives within the bounds of law and custom; nor does the Bank seek to sever its servants from their rightful bondage to either.’

‘I have heard otherwise,’ said the king, almost as if he were accusing Alfric of mistruthing.

‘My liege,’ said Alfric, ‘I cannot answer Rumour, for Rumour has ten thousand tongues and I have but one.’ ‘Hmmm,’ said the king.

Thinking.

Then:

‘You travelled by night.’

Alfric kept his face blank. This was no time to show impatience. But Alfric liked to do business in an efficient manner; and not for nothing was the king known as He Who Talks In Circles.

‘Night is a strange time to travel,’ continued King Dimple-Dumpling. ‘Particularly when night is Her chosen time.’

‘My duty bids me to rule the night,’ said Alfric. ‘I cannot permit Her forays to keep me from the dark. I am a Yudonic Knight.’

‘Who fears nothing,’ said the king.