The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (101 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

When Roosevelt arrived in Colorado Springs following a speech in Clayton, New Mexico, with plans to climb Pikes Peak, reporters were still covering his every move. Love him or hate him, Roosevelt made good copy. Once again he used hunting as his hook, arousing a burst of regional western pride. For three weeks he would dwell with the blood of bears, boots in the stirrup, stubble on his face. For Roosevelt the Rockies were always the Alps without handrails, and he promoted them as such. Not since Andrew Jackson had America had a president who was such a celebrity. Wherever Roosevelt went now, he would wave a bandanna to express solidarity with the crowds. But speaking in front of 10,000 people

gathered at the Santa Fe station in Colorado Springs, Roosevelt pleaded with both well-wishers and the press to allow him uninterrupted privacy in the wild. “One thing you cannot do on a hunt, and that is to carry a brass band,” Roosevelt said. “You cannot combine hunting bears with your Fourth of July celebrations. I am going to beg the people of Colorado to treat me on this hunt just as well as the people of Oklahoma treated me on the wolf hunt.”

71

Roosevelt shelved world affairs and domestic policy while in the Rockies, preferring a wintry saddle blanket to wire reports, and only one major news item seized his attention. The celebrated U.S. Senator from Connecticut, Orville H. Platt (not to be confused with Thomas Platt of New York), had died at age seventy-seven. The last time Roosevelt had seen his Republican friend—best known in history for the Platt Amendment of 1901, which offered Cuba self-determination after the Spanish-American War—Platt’s face was alarmingly drawn and gaunt, and a rattling cough had somehow caused his complexion to lose its luster: his skin was sepia-tinted. When Platt had tried to laugh, there was only a faint sound, and Roosevelt had known he wasn’t long for this world. “It is difficult to say what I think of Senator Platt without seeming to use extravagant expression,” Roosevelt had said of Platt at a dinner earlier that year. “I do not know a man in public life who is more loved and honored, or who has done more substantial and disinterested service to the country. It makes me feel really proud, as an American, to have such a man occupying such a place in the councils of the Nation.”

72

Deeply saddened, Roosevelt wanted to create a living memorial for Platt. In the Wichitas, he had heard about a system of freshwater and mineral springs south of Oklahoma City, less than two hours north of Dallas.

73

In 1902 the Chickasaw and Choctaw had ceded the best 640 acres of these freshwater springs to the Roosevelt administration. As at Hot Springs National Park (in Hot Springs, Arkansas), the gateway town of Sulphur, Oklahoma—otherwise a nothingville—had built hotels, hoping to attract tourists to the curative waters. The community, however, had a problem with sinking wells and hoped the federal government would someday come to the rescue.

74

Roosevelt now decided that the so-called Seven Springs area would make a terrific national park. He refused to wait until Oklahoma became a state, with large acreage carved out for Indian reservations, and there was little political disadvantage to naming the springs after Platt, even though the senator had never visited south-central Oklahoma (he had been a member of a committee on Indian Affairs, however). On June 29,

1906, Roosevelt (through a special act of Congress) declared the Seven Springs area Platt National Park—his latest park after Crater Lake, Wind Cave, Sully’s Hill, and Mesa Verde.

75

At a deliberate pace, the U.S. government added infrastructure to the Seven Springs area, including the Lincoln Bridge (completed in 1909). Besides featuring the springs, the park was surrounded by undisturbed grasslands.

76

(In 1976 the National Park Service renamed Platt the Chickasaw National Recreation Area. But as a lasting memorial, a Platt District in Sulphur was designed to recognize Platt National Park’s seventy-year history.

77

)

On April 24 the

New York Times

reported “The President’s Return.” Worried about difficulties with the Panama Canal, labor riots in Chicago, anarchy, and high tariffs, Roosevelt had decided to shorten the Colorado leg of his holiday by five or six weeks. The

Times

lamented that Roosevelt, “the hardest working man in the country,” couldn’t enjoy the Rockies longer. Most presidents are criticized for taking vacations because they may be caught off guard by an unexpected international crisis or a domestic crisis such as a strike. But Roosevelt was immune from such criticism. In fact, the

Times

(and other newspapers) thought he needed

more

time to enjoy himself, catch coyotes, and hunt grizzlies.

78

Of course, Roosevelt didn’t slip out of Colorado in the dead of night. The state threw a huge open-air revivalist meeting in Glenwood Springs to honor him on his departure. With the Old Blue Schoolhouse as a backdrop, ranchers who had ridden in to Glenwood Springs from Newcastle, Rifle, and half a dozen other nearby towns said

adios

. It was quite a pageant. Instead of sprucing up for the farewell, Roosevelt wore filthy blue jeans, a slouch hat, a soiled bandanna, a sheepskin jacket, and a blue cotton workman’s shirt. Because it was Sunday, Roosevelt asked that services be held under God’s blue sky with the green grass serving as pews. The sunshine in the upper air, the president maintained, was more inspiring than light filtered through stained-glass windows. An organ was rolled out onto the schoolhouse porch, and old-time hymns such as “Rock of Ages” were sung. A Presbyterian minister asked Roosevelt to say a few words to the God-fearing men and women of the Rockies. Thereupon, Roosevelt unleashed a sermon about the strenuous life, peppering his speech with cowboy jargon. At the end of this oration he announced that he would shake every hand offered him in Glenwood Springs. “There are a many of you,” he said, “so don’t stampede or get to milling.”

79

A week later, on May 7, Roosevelt hosted a good-bye dinner in Glenwood Springs. This was the final good-bye. All Roosevelt could do, however, was talk on and on about Colorado’s bears. Lambert had captured

some of these bears with a Kodak camera, but other bears weren’t so lucky. Roosevelt had been routinely bringing his bear skins to a local taxidermist, Frank Store, who mounted them in record time. Interestingly, Roosevelt requested that his half dozen or so bears be stuffed closed-mouthed. He had these trophies shipped as quickly as possible to Dr. C. Hart Merriam in Washington, D.C., where casts were also made of the bears’ footprints, so that the Biological Survey could glean precise scientific data from the samples. As usual, Roosevelt wrote up his outdoor notes to accompany the trophies.

Although Roosevelt did not bring back a grizzly cub to Alice (as promised), he did adopt a small black-and-tan terrier named Skip, whose new home would be the White House. Skip was a gift from Jake Borah to the president during his last few days in Colorado. Roosevelt and the dog, which never barked, had become inseparable friends. To Roosevet’s delight, Skip actually climbed trees to go after chased game.

80

While Roosevelt read books in Colorado for relaxation, sometimes going for three or four hours straight, little Skip would obediently sit in his lap, petted as the pages were turned.

“Archie simply worships Skip, who is developing into a real little boy’s dog and accepts with entire philosophy being carried around by Archie in any position,” Roosevelt wrote after he returned to Washington. “He has won the hearts of all the family except Mother, who I think resents his presence a little as a slight upon Jack. Yesterday she praised him—you know the kind of praise I mean—‘Yes, he is a cunning little fellow and friendly, of course. In fact, he is friendly with

everyone

.’”

81

VI

While Roosevelt was in Colorado, Edith had decided to purchase a little cabin for her husband in Albemarle County, Virginia, fourteen miles south of Charlottesville. She called it Pine Knot; a favorite phrase of her husband. By a happy coincidence the first lady had journeyed to Keene, Virginia, on May 6 to spend time with Joe and Will Wilmer (family friends). Both Ethel and Archie accompanied her. The Blue Ridge Mountains had long attracted Roosevelt, who particularly liked Jefferson’s

Notes on Virginia

. Edith must have known this. Besides enjoying the countryside, she was looking for a wilderness cabin where Theodore could escape Washington’s hubbub to “rest and repair.” She was tired of seeing him traipse off to Colorado for weeks every time he needed to return to the outdoors. On the Wilmers’ horse farm, tucked away among red and white oak, red cedars, dogwoods, red maples, and black cherry trees, was a rustic

worker’s cabin. Almost on the spot she purchased the cottage, plus fifteen acres, for $280, although the deal didn’t go through at the bank until June 15. (She purchased an additional seventy-five acres in 1911.

82

)

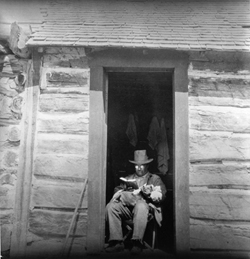

Roosevelt loved reading books on nature, hunting, and literature. Here he is with his little dog Skip on his lap in a Colorado cabin.

T.R. in Colorado cabin with Skip. (

Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)

Returning to the White House with Skip, the president was full of stories about Oklahoma’s wolves and Colorado’s bears. Wildlife photographs taken by the versatile Dr. Lambert were being developed in a darkroom. Anxiously, Roosevelt waited to see the photos with Catch ’Em Alive Jack. The whole experience at Big Pasture–Wichitas was imprinted on his mind like a brand. Quickly, he ordered the paperwork drawn up to create the Wichita Forest and Game Preserve. He signed the executive order on June 2, 1905, and transferred the newly formed Forest Service headed by Gifford Pinchot to the Department of Agriculture. At Merriam’s Biological Survey, last-minute legalities were being completed to create two new federal bird reservations in Michigan: Siskiwit Islands and Huron Islands.

83

Lawyers at the Department of the Interior were also looking into preserving some interesting geological formations and archaeological ruins in the Southwest, such as Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde. “Arizona and New Mexico hold a wealth of attraction for the archaeologist, the anthropologist, and the lover of what is strange and striking and beautiful in nature,” Roosevelt wrote. “More and more they will attract visitors and students and holiday-makers.”

84

Edith was likewise bursting with news of the outdoors. All she could

talk about was Pine Knot—the two-story cottage in the middle of a bird paradise. A piazza, she said, offered views of open fields and the Blue Ridge foothills. Everything about the place, she believed, was ideal for solitude. Yet it was also a practical acquisition. While it was isolated from Washington, Pine Knot was not really too far from civilization. Only half a mile away was a general store, and Christ Church could be reached simply by walking across a horse pasture. And Pine Knot had historical significance which Edith knew her husband would cherish: it sat along Scottsville Road, where General Sheridan had marched 5,000 troops in 1865 on a maneuver to destroy the James River canal locks.

85

“Mother,” T.R. wrote to Kermit after returning from Colorado, “is a great deal more pleased with it than any child with any toy I ever saw.”

86

It was agreed that after Roosevelt concluded the Russo-Japanese negotiations in early June, he would head south to stay at Pine Knot for a few relaxing days. He could start a Virginia bird count there. Edith went first as an advance scout, setting up furniture and making sure the potbellied stove was in working order. This was not an Adirondacks hunting lodge but a cabin in the rustic tradition of John Burroughs’s Slabsides in New York. On June 9, after extracting a promise from Russia and Japan to negotiate face-to-face, Roosevelt took the Southern Railway (train No. 35) to Red Hill, Virginia. A few locals were at the station when he arrived. All T.R. offered them was a boyish declaration that he was glad to become a Virginian homeowner.

After sleeping one night in the ocher-colored cottage—which had a cedar roof, dark green shutters, and a hardwood tree growing

inside

—Roosevelt declared Pine Knot “the nicest little place of the kind you could imagine.” Not everybody in Blue Ridge country, however, was happy to have President Roosevelt as a neighbor. Anger over the dinner with Booker T. Washington had made Roosevelt persona non grata in parts of Albemarle County. No reconciliation with these bigots was possible. Also, Roosevelt’s admiration for General Sheridan—who was to Virginians what General Sherman was to Georgians—didn’t endear him to the locals. Furthermore, Roosevelt’s attempts at taking land in the Blue Ridge Mountains for federal forest reserves had angered local timber companies. So, this was hostile country to some degree. Nevertheless, Roosevelt refused Secret Service protection; that was a reluctantly agreed upon precondition with Edith. He instead chose to sleep with a pistol at his bedside, thumbing it open to check the bullet chambers before blowing out the light. A real man, Roosevelt believed, protected his own family in the woods.