The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (57 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

As Pinchot and La Farge waited to be called into the governor’s office, they grew slightly nervous. Understanding that the wildly popular Governor Roosevelt was the most celebrated outdoorsman alive, they hoped to form a united front with him on the pressing forestry issues of the era. Pinchot’s principal concern was that every hour, the United States had fewer trees than an hour before. Deforestation in such places as the Olympics, the Cascades, and the Front Range of the Rockies was now widespread in land tracts not protected by the Cleveland Reserves. (And it was taking place even in some acreage that was supposedly protected.) Too many unscrupulous deals for U.S. government leases were being made in and around the western reserves. Pretty soon all the raw land west of Denver might look defiled like in Haiti, China, and Italy. The dire warnings in

Man and Nature

had to be heeded. The lack of water for irrigation was also a serious problem in places such as California and Nevada. Pinchot essen

tially promoted two remedies: creating more forest reserves and allowing some regulated timbering within their boundaries. Pinchot’s scheme was to enlist Governor Roosevelt in the great cause. Roosevelt—a politician who refused to sit on the dais while the band played—was his best hope for developing a new, widespread public awareness of the perpetual benefits of the forest realm. America had to remain a land with luxuriant woods and verdant valleys. “We arrived just as the Executive Mansion was under ferocious attack from a band of invisible Indians,” Pinchot recalled in his autobiography

Breaking New Ground

, “and the Governor of the Empire State was helping a houseful of children to escape by lowering them out of a second-story window on a rope.”

22

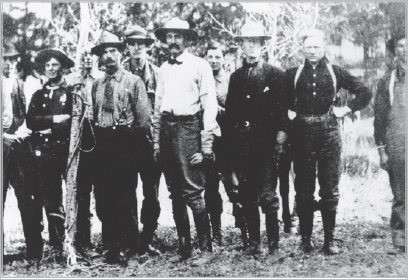

Gifford Pinchot and his forestry team

.

Gifford Pinchot and forestry team.

(Courtesy of Gray Towers National Historic Site, Milford, Pennsylvania)

What a grand time Pinchot and La Farge ended up having in Albany with the famous Rough Rider! They cut up like misbehaving kids and acted as if they were trail mates; and Governor Roosevelt told numerous stories about adventures off the beaten path. All three shared a gratifying intellectual curiosity about the natural world. Roosevelt, in fact, acted not as a governor with authority and power, but as a fellow wilderness enthusiast, a fraternity brother from the world of the Boone and Crockett Club. He was excited by the talk of the Pacific Northwest and the Front Range, and his facial muscles flexed as he spoke, while his knees bounced with boyish enthusiasm, as if he were overcaffeinated. Any moment, it seemed, he would climb out the window on a rope himself then break

another plate-glass to get back inside the mansion. Keenly observant, Pinchot noted that when the Adirondacks were mentioned Governor Roosevelt perked up like a border collie eyeing sheep. Lake Tear-of-the-Clouds, Algonquin Peak, Upper Ausable Lake, Lake George—such natural wonders had magical connotations for Roosevelt, as they would later for the painters O’Keeffe and Hartley.

Capitalizing on the governor’s love of this natural setting, Pinchot hoped to form an alliance with Roosevelt that afternoon and evening, for preserving the deciduous hardwoods of the Adirondacks—especially the sugar maple, American beech, and yellow birch. What was supposed to be a short chat with the governor on their way to examine forested acreage owned by the Adirondack League Club (renamed the Tawahus Club in 1897), turned into hours of rollicking storytelling about the outdoors. Clearly, Roosevelt was fascinated to hear about the old-growth forests of the Olympics and Cascades, which Pinchot had recently toured (and photographed) as President McKinley’s “confidential forest agent.” But Roosevelt’s immediate concern as governor was the deterioration of the Laurentian mixed forests from Nova Scotia to the bogs of Lake of the Woods in Minnesota, especially in the Adirondacks and Catskills.

That first evening together, after hopscotching from one topic to the next like red-bellied nuthatches scouring for insects at one decayed stump after another, Roosevelt and Pinchot—in an act of primordial male bonding—put on gloves and boxed. Weaving and jabbing, throwing right and left jabs, ducking punches, Roosevelt was able to size Pinchot up as an honest man with a killer instinct. “Pinchot truly believes that in case of certain conditions I am perfectly capable of killing either himself or me,” an amused Roosevelt wrote. “If conditions were such that only one could live he knows that I should possibly kill him as the weaker of the two, and he, therefore, worships this in me.”

23

But that evening it was the six foot and two inches tall Pinchot who seemed the stronger—at least at first. “I had the honor,” Pinchot wrote in his autobiography, “of knocking the future President of the United States off of his very solid pins.” Fellow Boone and Crocketters had been saying that the patrician Pinchot was, surprisingly, a “man’s man,” who could “outride and outshoot” anybody. Roosevelt put the Yalie’s reputation to the test and came out with a favorable impression.

24

Roosevelt, not to be defeated, shrugging off the boxing loss, immediately challenged Pinchot to a wrestling match, anxious to show off some pinning techniques. This time Roosevelt easily won the match. The score was now even at 1 = 1. Shrewdly Pinchot decided that it was best to

safeguard the tie; a split decision, he reckoned, was the best outcome in dealing with a family friend with such a large ego and such a competitive disposition. Sometime during the punches and take-downs, Roosevelt decided to trust Pinchot; he liked the Old Boy’s gameness, the way he didn’t refuse a challenge, his aristocratic mien, and his abiding sense of noblesse oblige. And, more important, Pinchot wholeheartedly shared Roosevelt’s ideals regarding scientific forestry. Pinchot was also impetuous, and the governor liked impetuousness in a man. Patience, Roosevelt believed, was a bent card that the dim and selfish played. Grinnell remained Roosevelt’s muse on wildlife protection issues, but the irrepressible Pinchot, Roosevelt’s junior by seven years, now was effectively anointed his guru on forest policy. Roosevelt and Pinchot formed an alliance that would have a profound effect on the modern conservation movement. Together, they would promote America’s forests with firm confidence and zeal.

Ironically, even though Pinchot advocated forest conservation, he was seen as a sellout by thoroughgoing preservationist friends of Roosevelt, such as John Muir and William Temple Hornaday. The fact that Pinchot wanted to allow regulated tree harvesting in the Western Reserves was nearly anathema to them. Governor Roosevelt knew about this, but he thought the put-downs unfair. After all, Pinchot’s family was about to donate $150,000 for Yale University to start a forestry school and was starting a forestry camp at Grey Towers to teach a new generation wise use policy.

25

“Gifford Pinchot is the man to whom the nation owes most for what has been accomplished as regards the preservation of the natural resources of our country,” Roosevelt later said. “He led, and indeed during its most vital period embodied, the fight for the preservation through use of our forests.”

26

Pinchot embraced Governor Roosevelt’s notion that New York should have one superintendant who could replace the five-man Fisheries, Game, and Forest Commission.

*

Roosevelt would promote this concept, saying that a “system of forestry” needed to develop “along scientific principles.”

27

Roosevelt also implored the chief of the U.S. Forestry Division to help him preserve the Adirondacks as completely as Yellowstone and Yosemite. The east coast population centers, he believed, needed wilderness parks to help revive city dwellers’ spent spirits. As Pinchot and La Farge headed to the Adirondacks to help establish a land management

plan, setting up camp at Lake Colden, located midway up the mountain, they had the governor on their side. Roosevelt, in fact, gave them carte blanche to use his name as expedient. Roosevelt was starting to understand that Pinchot wasn’t merely a forester but a revelation.

What really sealed the deal between Roosevelt and Pinchot was their shared admiration of 5,344-foot Mount Marcy, the tallest peak in New York. More than thirty years after Roosevelt first saw its summit, Mount Marcy (named in 1837 after Governor William Learned Marcy) still had magnetic appeal to him. (Sometimes Mount Marcy was called Tahawus, Cloudsplitter, or High Peak of Essex by locals.

28

) Compared with four larger eastern summits—Mount Mitchell, Mount Washington, Clingman Dome, and Mount Rogers—Marcy was a “bump” yet its slopes were still covered by primeval forest.

29

Now, in freezing February temperatures, Pinchot and La Farge were planning on snowshoeing to the top of Mount Marcy with the help of two Indian guides; theirs would be only the second ascent ever attempted in winter. Upon hearing about their planned adventure, Roosevelt lit up like a Christmas tree. Bully! If he hadn’t just started his job as governor, he would have joined the Ivy League explorers on the historic climb. Reacting as if they were about to go to the North Pole or Antarctica, Roosevelt demanded that Pinchot and La Farge report to him in Albany after the ascent. Hungrily, like a city editor, he wanted details of the twenty-foot snow drifts and ice squalls. The trip to Mount Marcy, Pinchot recalled, was “exactly in his line.”

Yes, yes, both Pinchot and La Farge vowed to Roosevelt, they would visit Albany with firsthand reports of the summit immediately following their ascent. They had suddenly become Roosevelt’s pro tem wilderness correspondents. True to their word, Pinchot and La Farge braved the mountain, but because of a blizzard it was rougher than they expected. Even Governor Roosevelt would have deemed them demented for challenging Old Man Winter so brazenly. As in tundra country, all the evergreens were, as Pinchot put it, “a monument of snow.” Pecking out footholds wherever possible, Pinchot and La Farge pressed forward, half a step at a time, constantly shivering. Underdressed for the arctic temperatures, they nevertheless progressed incrementally in the squall. Both guides quit: one claimed that his snowshoes were too long, and the other had developed numbness in a leg. Normally, the pragmatic Pinchot would have retreated, recognizing that mountaineering in such brutal weather was like Russian roulette: one Canadian cold front could bring death faster than sleep. But he didn’t want to tell Governor Roosevelt he had failed. So Pinchot and La Farge, minus the guides, pressed on.

Grant La Farge later wrote about the climb for

Outing

, saying that the gale-force wind was like a “battery of charging razors.”

30

Also, visibility was no better than what might be seen through a sheet. About three-quarters up Mount Marcy, they were reduced to crawling on hands and knees to reach the summit. Pinchot said that he held his “head down in the squalls” and stopped “every minute or two to rub my face against freezing.”

31

Even their mustaches and eyelashes froze. Eventually, through sheer willpower, they arrived at the summit’s signal pole, but they saw nothing but snow and ice. “Got to the top,” Pinchot wrote in his diary. “Foolish.”

32

Worried about contracting grippe or whooping cough, Pinchot and La Farge snapped photographs of each other and then crawled back down Mount Marcy as quickly as possible—dizzy, terrified, suffering from frostbite.

33

The three-day ordeal was the most dangerous of their lives. Once they were warm by a lodge fire, Pinchot and La Farge, to their horror, learned that they had been climbing in the blizzard of 1899—called the “Storm King” by the press. Unprecedented arctic temperatures had socked and crippled the entire Northeast. Water pipes, it was said, had burst throughout every county in New York. The weight of snow had caused house roofs to cave in. They were lucky—very lucky—to be alive. Both men later retold the story of ascending Mount Marcy as if they were characters in a knockabout comedy.

Their harrowing climb, however, produced one positive result. Returning to the executive mansion in Albany as promised, Pinchot and La Farge had wild stories to regale Governor Roosevelt with. Feeling left out, Roosevelt announced that he too would conquer the Adirondacks’ tallest summit come August or September when the weather got better. Full of “dee-light,” pleased to hear about their mountaineering antics, Governor Roosevelt had come to embrace Gifford Pinchot as a new member of his extended outdoors family. Given how close their fathers had been, they fell into an easy camaraderie as if they were long-lost blood brothers. (La Farge, an early member of Boone and Crockett Club, had long ago received T.R.’s stamp of lifetime approval.)

34

II

One New York leader Governor Roosevelt was constantly trying to outfox was Thomas “Boss Platt. Ever since he served as a New York assemblyman from 1882 to 1884, Roosevelt refused to join Platt’s Republican rubber stamps. He was unimpressed by Platt and distrusted him—Platt had flunked out of Yale and had worked as a pharmaceutical salesman

and, in Michigan, as a lumber operator. Roosevelt, however, was deferential to Platt—his elder by twenty-five years—merely because political expediency demanded it. He didn’t want to spar unnecessarily with a slugger. As past president of the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company, Platt knew at least one thing about geology: that the land had glorious treasures which could be extracted. He considered nature sightseeing a fey enterprise. He had been elected to the U.S. Senate from New York in 1896, and when his photograph appeared in the

New York Tribune

on January 21, 1897, it was the first halftone reproduction ever published in a daily newspaper. As of 1899, only Governor Roosevelt was a more recognizable New York personality than the fit, trim, bushy-sideburned Platt. In his dogged, confident, shrewd, relentless way, Platt was a formidable counterpart to Roosevelt; their values, however, were at the opposite ends of the Republican Party’s spectrum. Nevertheless, after only a month in office, Roosevelt wrote to John Hay that, to his surprise, he was “getting on well” with Platt.

35