The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (61 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Besides the FAS and Governor Roosevelt, Dutcher now had the U.S. government on his side. And once again, the “velvet hammer” of the U.S. conservation movement, John F. Lacey, congressman from Iowa’s Sixth District, entered the drama. Lacey was committed to the fate of avian species in his home state, such as blue-gray gnatcatchers and Henslow’s sparrows. The Lacey Act of 1900—which he sponsored six years after the Yellowstone Protection Act—made it illegal to transport protected birds across state lines. It was the first federal law protecting game.

80

According to the

Federal Wildlife Laws Handbook

, the Lacey Act authorized the secretary of the interior to “adopt measures to aid in restoring game and

other birds in parts of the U.S. where they have become scarce or extinct and to regulate the introduction of birds and animals in areas where they had not existed.”

81

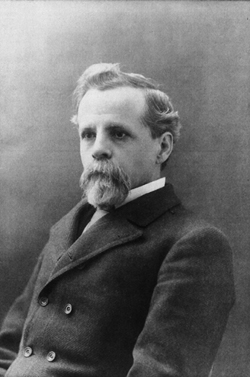

Congressman John F. Lacey of Iowa’s Sixth District did more to protect migratory birds than any other politician in American history besides Theodore Roosevelt

.

Congressman John F. Lacey.

(Courtesy of the University of Iowa Special Collections)

Under consideration since 1897, the Lacey Act finally passed the House on April 18, 1900, and then, three weeks later, on May 25, passed the Senate. President McKinley signed the Lacey Act into law with no regrets.

82

A new conservationism had arrived in America. No longer could you kill a snowy white heron along the Indian River, for example, and sell the feathers to Macy’s department store in New York. As Governor Roosevelt saw it, as a consequence of this federal legislation (plus the Hallock Bird Protection law), Dutcher could now make a citizen’s arrest if he saw somebody illegally shoot a bird.

83

The landmark legislation, however, didn’t accomplish its immediate goal, for the financially stingy President McKinley initially employed very few game wardens. Worse yet, the state game laws weren’t really enforced. Still, the law of the land was now on the side of the conservation movement.

84

It would be up to the Audubon societies and AOU to figure out how to raise funds for wardens.

High-minded speeches like Roosevelt’s second annual message and legislation like the Hallock Bill and the Lacey Act were, of course, only the first steps in this reformist movement. Enforcing change—in this case, closing up the millenary industry’s loopholes and confronting market

hunters and fishermen bent on exterminating pelicans—proved to be difficult. Suddenly, the heavily armed plume hunters in Florida were pitted against newly organized conservationist groups like the FAS and AOU in a what were known as the “feather wars.” This protracted feud flared up and became deadly between 1900 and 1920. Under the Lacey Act, however, a poacher could no longer bribe or intimidate a local judge to turn a blind eye toward the slaughtering of birds. Now, for the first time, accused poachers operating in Florida would have to go before a federal judge, who would be fully cognizant that the federal government wanted the act vigorously enforced.

Refusing to capitulate, and antagonistic toward what they perceived as Yankee hunting restrictions, the plumers in Florida stood their ground and defied the law. It was reminiscent the blowback in response to the Washington’s Birthday Reserves or Cleveland Reserves. Abetted by the millinary industry, many intransigent Florida market hunters simply refused to pay the new laws any mind. They believed in their God-given right to exterminate species; Washington, D.C., could shove its bird laws as far as they were concerned: the Second Amendment gave them the right to shoot whatever they damn well pleased. Roosevelt—the “born bird-lover”

85

—scoffed at such backward, neo-Confederate thinking. Some plumers, however, decided that it was legally safer to hunt in the North, in the “prairie potholes” of Canada and the upper Midwest, rather than in the southern states, which encompassed the cross-continental bird migration route known as the Mississippi Flyway; in Minnesota and Wisconsin, unlike Florida, wardens weren’t patrolling the “Father of Waters.”

Nevertheless, a huge pro-Audubon Society change had occurred. And to the consternation of the millinary industry, its worst enemy—Theodore Roosevelt—seemed to be a short-fused time bomb. Within four months after the legislation in Tallahassee, he would be president of the United States.

T

HE

A

DVOCATE OF THE

S

TRENUOUS

L

IFE

I

B

y the time the Lacey Act had passed in 1900 Governor Theodore Roosevelt and John Burroughs had solidified the friendship that began at their first meeting at the Fellowcraft Club. Burroughs now had a face full of hard-earned wrinkles, and he had grown a long, bushy beard as white as beach flax; he resembled Charles Darwin as an old man (the British naturalist had died in 1882), or Father Time. There was about him an outdoors aura of a solitary holy man or troglodyte. From 1889 to 1900 Roosevelt and Burroughs had regularly met for lunch, discussed bird laws, and swapped books. The two men shared the admirable traits of enjoying a well-turned phrase and never keeping the inkhorn dry. During his tenure as governor Roosevelt and Burroughs each managed to publish three books. Together they were proud Audubonists. “I send you a copy of my

Big Game Hunting

,” Roosevelt wrote to Burroughs on May Day 1900. “It is really a combination of two volumes. In the second part, I wish you would look on p. 65 and before and after, where I speak about some birds. Again and again as I have listened to those plains birds I have longed to have you hear them, and I have longed even more to have you hear the bull elk and the great wolves.”

1

In 1899 James Bryce deemed Roosevelt “the hope of American politics” Burroughs, however, saw the Colonel as the great public naturalist of the future.

2

An alliance of great importance to the wildlife protection movement was forged between Roosevelt and Burroughs. Burroughs, in fact, invited Roosevelt’s twelve-year-old son, Ted—who had straight jet-black hair and a face full of freckles—to spend a long weekend with him, hiking around the clear streams near his rustic cabin, Slabsides (built in 1895 on a bog that was once a celery swamp).

*

3

According to Roosevelt, little Ted “grinned with delight” when he heard of Burroughs’s offer of hospitality. “How I wish I could be with you!”, Roosevelt wrote to Burroughs. “As I have written you, when out on the Ranch in the old days I

cannot say how many times I longed to have you there. It was only while I was in the West and on my ranch that I ever had much opportunity of really hearing bird songs. Of course I know our common birds of the East—the thrushes, bobolinks, etc., but it was only while I was on my ranch that I ever lived out of doors.”

4

Having Burroughs provide a guided tour around the Hudson River Valley was akin to having Thoreau describe the salient features of Walden Pond in a walk-around. Burroughs, Roosevelt believed, was the top-drawer nature writer of all time. His voice and memory were those of a master. Burroughs’s book of nature essays,

Far and Near

, included “Babes in the Woods,” about his fine time with Ted exploring Black Creek.

5

Eastern bluebirds—nesting in dead tree stumps—became the species du jour on their fine tramp. Burroughs explained to Ted the difference between the plaintive female note and the more ardent note of the male. The red, white, and blue eastern bluebird had become signature birds to Burroughs.

6

“Never in your life have you given more happiness than to the small boy who spent last Saturday and Sunday with you,” Governor Roosevelt wrote to Burroughs on May 21. “I thank you most sincerely for your kindness to him. Ted is a good little fellow and he appreciated every moment of his stay. He has really been very interesting over of his experiences, notably the conduct of the two parent bluebirds after you by accident broke down the stump containing their nest and then put it up again.”

7

With Burroughs as his primary muse, Governor Roosevelt had entered the “citizen bird” movement full-throttle. Along with Frank M. Chapman, William Dutcher, and a few others, Roosevelt truly thought of himself as part of the guild of professional naturalists. And Burroughs was their éminence grise. Just as Theodore Roosevelt Sr. had gotten immersed in the humane movement, his son now believed in the moral impact of Darwin’s theory: that benevolence toward other species was compulsory, that society had a sacred obligation to take care of lower species like birds.

8

This “moral” Darwinian impulse had first started fomenting when T.R. had read

Wake-Robin

at Harvard University. (In 1859, when Roosevelt was one year old, Burroughs had written in his

Notebook

the evolutionary sentiment that “from a single atom, by infinite modification, Nature builds the universe”). To Burroughs,

The Descent of Man

was a miraculous “model of patient, timeless, sincere inquiry; such candor, such love of truth, such keen insight into the methods of Nature, such singleness of purpose and such nobility of mind, could not be easily matched.”

9

Roosevelt’s heartfelt appreciation of Whitman, Emerson, and Darwin

grew as he read more and more of Burroughs’s books. If Captain Reid was too juvenile and Charles Darwin too scientific, Burroughs fell into the middle zone; he wrote in a way Roosevelt could emulate. Burroughs, you might say, further stoked

the

key ingredient to Roosevelt’s penchant for faunal naturalism: compassion for all wild creatures, especially birds. Once Burroughs became the first vice president of the New York Audubon Society, in fact, Roosevelt would do whatever he could to help the organization (of which he was also a member) flourish. “I know your Society will frown upon the milliner’s use of bird skins,” Burroughs wrote in 1897, accepting the vice presidency. “I hope it will also discourage the senseless collecting of eggs and nests which so many young people take up as a mere fad, and which results in the destruction of so many of our rarer birds.”

10

To Burroughs,

On the Origin of Species

was a “true wonderbook”—the exact sentiment Roosevelt had toward it. The debt both naturalists felt they owed Darwin could never be repaid. Both men learned to scoff at Darwin’s critics as dimwits who couldn’t comprehend basic scientific laws of nature. Only Shakespeare and Emerson, they believed, had a comparable grip on the universal condition. Darwin “is the father of a new generation of naturalists,” Burroughs enthused in his journal. “He is the first to open the door into Nature’s secret senate chambers. His theory confronts and even demands the incalculable geological ages. It is as ample as the earth, and as deep as time. It mates with and matches, and is as grand as, the nebular hypothesis, and is the same line of creative energy.”

11

What about the role of God in all this orthodox Darwinian celebration? Both Roosevelt’s and Burroughs’s views can be summed up in a single, often quoted line: natural selection may “account for the survival of the fittest, but not for the arrival of the fittest.”

12

God was the one who created Darwin’s world order. Independently, Roosevelt and Burroughs both understood that Darwin believed natural selection was a

process

, not a cause.

13

“The influence of Darwinian thought on Roosevelt’s generation,” the historian John Morton Blum noted in

The Republican Roosevelt

, “was profound.”

14

Realizing that calling Burroughs “John” was too pedestrian (and “Mr. Burroughs” too formal) Roosevelt settled on “Oom John”—

oom

being Dutch for uncle. Obviously, this was meant not in the sense of a “Dutch uncle” but as a salutation expressing deep and abiding love and kinship for time immemorial. Even though Burroughs continued to call Roosevelt “Mr.” or “Governor” or “Mr. President”—old-school propriety to the maximum degree—to T.R. he was Oom John, the wisest mentor of them

all. Oom John, in fact, approved of the Boone and Crockett Club books and thought his politically powerful young friend’s book

The Wilderness Hunter

, in particular, excellent. There was, Burroughs recognized about Roosevelt, a fine naturalist buried under the yarns about twelve-point antler trophies and the Rough Rider’s braggadocio. Not that Burroughs minded hunting per se. Like Roosevelt, Grinnell, and the others in the Boone and Crockett Club, Burroughs believed seasonal hunting was an imperative for thinning out herds and game-bird flocks. Roosevelt was in awe of Oom John’s ability to notice field marks on birds—color, feather pattern, eye-catching markings, gender, and shape. But Burroughs preferred Roosevelt’s more poetic side, admiring the way he wrote about nighthawks flying over a canyon or the coloration of Old World chats. To Roosevelt there was no higher compliment than Oom John’s writing to him to say that he admired Roosevelt’s hunting books because they were infused with such “good sound naturalist writing.”

15

II

Coinciding with his second annual address as governor of New York was Roosevelt’s publication of

The Strenuous Life

, his essays expounding his view of the hardy American character being replenished by the outdoors life. Overcrowded and unsanitary big cities, where the air was foul and pestilence was bred, where whole blocks were nothing more than slums, were incompatible with health. In speeches in New York City that month—one given at the Boone and Crockett Club’s annual banquet—Roosevelt stated that the time had arrived for wildlife preservation, clean rivers, antipollution laws, and wise use of forests. There was an intensity to Roosevelt during those opening months of 1900 that was almost electric. Writing to Henry L. Sprague, for example, Roosevelt mentioned for the first time that he was fond of the West African proverb “Speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far.”

16

To historians this proverb has become emblematic of Roosevelt’s imperialistic belief that the United States should maintain a robust army and navy while using diplomatic channels in foreign affairs, dangling the threat of war over adversaries’ heads. “Roosevelt loads his gun too heavy,” Burroughs wrote in his diary. “The recoil hurts him more than the shot does his enemy. He is bound to make a big noise but the kick of the gun is so much power taken from the force of the bullet. People react vigorously against him as they always do to his surplus verbal energy.”

17

Like in foreign afairs, there was little soft speaking from Governor Roosevelt regarding forestry and wildlife protection; there was only the

big stick. Such intimidation tactics on behalf of wildlife protection, particularly against the millinary industry, often worked. On February 10, for example, a few weeks after his second annual message, the state legislature revised Chapter 31 of the General Laws and approved Act (Ch 20) for the protection of forests, fish, and game. New York state now had the most progressive conservation protection laws in the United States (with the possible exception of Vermont). As the historian G. Wallace Chessman noted, Roosevelt squared off against the powerful Utica Electric Light Company when it tried to purchase private lands in the Adirondack Park; protecting birds, he said, came first.

18

By March 1900 Roosevelt had also won approval for the land, funds, and management for Palisades Park, which he had deeply wanted. Largely because of Roosevelt’s opposition to quarrying, the ruination of the cliffs had stopped overnight. That success spurred Roosevelt onward. If New York and New Jersey could create a joint park at the Palisades, he didn’t see why Wisconsin and Michigan—to give just one example—couldn’t do the same with the islets surrounding Beaver Island in Lake Michigan. Meanwhile, Roosevelt began promoting Gifford Pinchot as “the best authority on forestry in the country.” When some people raised the objection that Pinchot was “too political” in his work at the Forest Division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Roosevelt squawked. Blithe irresponsibility had guided America’s forest policy for far too long; Pinchot was the intellectual antidote. “Pinchot has no more to do with politics than the astronomers of the Harvard observatory have,” Roosevelt said in Pinchot’s defense. “All he is interested in is his forestry work.”

19

As for the oyster beds of New York, Roosevelt was searching for their protector. Uncle Rob had been conducting all sorts of experiments in oyster farming at Lotus Lake, and his nephew was probably intrigued. Basically, Roosevelt wanted to recruit someone like Seth Green to come work as the “oyster protector” at the Fisheries, Game, and Forest Commission. Writing to the conservationist George McAneny, Roosevelt said, “The man appointed to this position should of course have some literary knowledge, some scholarly attainment, but he must know practically about oysters and be able to row and sail and handle himself on mud flats.”

20

Connected to Roosevelt’s concern about oyster beds were his hyperactive efforts to promote scientific water resource management and to stop reckless water pollution by the timber companies.

21

Obviously, as New York’s governor Roosevelt engaged in other reformist measures not connected to forestry or oyster conservation. He established a state hospital to care for crippled and deformed children, promoted

consistent pharmaceutical standards, fought to end racial segregation in public schools, and demanded antiracism efforts in schools. Compulsory seating areas for employees in factories, he declared, were mandatory. Disapprovingly, he toured sweatshops with Jacob Riis, furious that such sickening squalor existed in America, stopping just long enough to ask the most pertinent questions about city services in the down-and-out neighborhoods. And his interest in integrating Native Americans into the main fabric of national life continued. For example, he pushed for compulsory education on the Alleghany and Cattaraugus reservations in New York. The time was long overdue, Roosevelt believed, for Native Americans to be given a fair shake. Long before the term “affirmative action” was in use, Roosevelt was promoting the concept on behalf of Indians. And he started corresponding with three African-American intellectuals whom he deeply admired: Booker T. Washington, William Henry Lewis, and Paul Laurence Dunbar.

22

By June 1900 Governor Roosevelt was described by the

New York Sun

as the greatest reformer in American politics. That month, as testimony to his meteoric rise, the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia nominated him to run as President William McKinley’s vice president, despite Mark Hanna’s fervent objections. (Hanna actually had a heart attack shortly after T.R.’s nomination, but lived.) Wearing a huge black top hat, Roosevelt had stood out at the convention amid a sea of straw boaters like, as Edmund Morris put it, “a tent in a wheat-field.”

23

He remained coy, however, about whether he wanted the official vice presidential nomination in the first place. Boss Platt understood that in any case Roosevelt would get the nod. Famously, he quipped, “Roosevelt might just as well stand under Niagara Falls and try to spit water back as to stop his nomination by the convention.”

24