The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (7 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

In the spring of 1868, Theodore’s parents traveled to Roswell to visit Martha’s relatives. A fascinating correspondence between mother and son has survived, illuminating young Theodore’s love of collecting all things wild. “I have just received your letter,” he wrote to his mother on April 28. “My mouth opened wide in astonishment when I heard how many flowers were sent to you. I could revel in the buggie ones. I jumped with delight when I found you had heard a mockingbird. Get some of the feathers if you can…. I am sorry the trees have been cut down…. In the letters you write do tell me how many curiosities and living things you have got for me…. I wish I were with you…for I could hunt for myself.”

41

Two days later the precocious nine-year-old responded to a letter from his father, angling for hard-to-find plants. “I have a request to make of you, will you do it?” Roosevelt asked his father drily. “I hope you will. If you will it will figure greatly in my museum. You know what supple jacks are, do you not? Please get two for Ellie [Elliott, his younger brother] and one for me. Ask your friend to let you cut off the tiger-cat’s tail, and get some long moos and have it mated together. One of the supple jacks (I am talking of mine now) must be about as thick as your finger and thumb

must be four feet long and the other must be three feet long. One of my mice got crushed. It was the mouse I liked best though it was a common mouse. Its name was Brownie.”

42

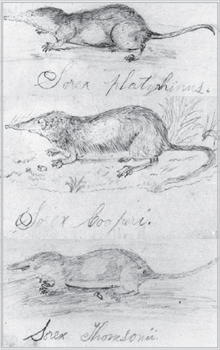

As a young boy Roosevelt not only collected live mice and a woodchuck but also sketched them in notepads, a few which have survived undamaged. Eastern moles were another favorite of the young Roosevelt, and in a series of drawings housed at Harvard he captured all the salient details of these blind underground tunnelers: flat fur; eyes covered with skin; the absence of ears; and side-facing feet ideal for digging. Then there are his fine sketches of robins and wrens. Clearly, Roosevelt was blessed with a mind that could absorb physical detail. His bird and animal drawings were quite accomplished for a boy of his age. To most children one field mouse was indistinguishable from another, but Roosevelt knew that a canyon mouse

(Peromyscus crinitus)

or a pinyon mouse

(P. truei)

was different from a cotton mouse

(P. gossypinus)

. And he didn’t recoil from drawing them.

43

III

An astonishing fact about young Roosevelt’s prodigious interest in nature was that he kept semi-regular diaries. Studying his unaffected scrawl and chronic misspellings brings crucial understanding and clarity to his later achievements as a conservationist and wildlife protectionist. Being a naturalist in the 1850s and 1860s was fashionable, and the young Roosevelt had caught the bug. Darwin had sounded a clarion call for a new generation of biological collectors, and Roosevelt had heard it loud and clear. Roosevelt called his first diary

My Life

and kept it between August 10 and September 5, 1868. That summer the Roosevelt family spent their holiday in Barrytown, a busy railroad depot and steamboat landing across the Hudson River. Leasing the country home of John Aspinwall, the Roosevelts immediately began exploring the Hudson River valley, which had recently been celebrated on canvas by such remarkable landscape painters as Thomas Cole, Jasper Cropsey, and Albert Bierstadt. Sitting on the riverbank, they could watch steamers, canal boats towed by tugs, and tall sails drifting by in silence.

44

Barrytown provided Roosevelt his first opportunity to hear the earth inhale and exhale without interference from the noise and stench of the industrial revolution. In virtually every diary entry throughout the late summer of 1868, Roosevelt wrote enthusiastically about animals he had either encountered or heard of in the dales of Barrytown. There were deer, big and small, to be studied; he learned how to analyze their tracks, like

an Iroquois or Algonquin scout in training. There were encounters with packs of wild dogs; mid-afternoon pony rides; times for feeding horses sweet grass, green meat, and bran mash; lazy hours reeling in bluegills at fishing ponds; walks along fast-running brooks teeming with crayfish, eels, salamanders, and water bugs (all easily trapped from the low bank); and strange spiderweb filigrees to analyze. Then there were the nests of wasps to fear and weasel holes to avoid when riding a pony. And, of course, bears (or at least rumors of bears)—young Theodore was ready to discuss bears at any time, night or day.

45

Influenced by Audubon and Darwin, Roosevelt started sketching birds and mammals in his notebooks. In these pencil drawings, he marks the sub-species variations of shrews.

T.R. sketches of mammals. (

Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)

Throughout his life, bears mesmerized Roosevelt. In

An Autobiography

, in fact, he wrote wide-eyed of Bear Bob—a former slave once owned by his mother’s family in Georgia—who had been scalped by an angry black bear’s claw.

46

(That violent, degrading spectacle haunted Roosevelt’s imagination.) Even at nine, Roosevelt saw bears—lumbering giants that can run as fast as a racehorse for short distances—as a symbol of wilderness. Enamored of their cunning, curiosity, and ferocity (when provoked), Roosevelt marveled that their acute sense of smell enabled

them to detect game from nearly one mile away. He also noted that bears belong to a mammal group referred to as plantigrade (i.e., flat-footed, in contrast to digitigrade animals, which walk on their toes, like cats and dogs). Young Roosevelt rejected the human-like Thomas Nast cartoons of these omnivores in

Harper’s Weekly

(popular in the 1860s) in favor of cutting-edge zoology books with exact details on nonretractile claws agility (among black bears only) in climbing trees. With scientific detachment, young Theodore would correct people who casually claimed that all bears hibernate in winter; they don’t, and such sloppy misconceptions annoyed him greatly.

47

For example, he believed bears were “wicked smart,” able to backtrack in their own footprints to shake hunting dogs off their easily detectable scent. Yet popular culture usually portrayed bears as slothful, honey-loving buffoons hiding in a den. Often black bears were written about as small cousins of grizzlies. To a degree, that assessment was fair. But it bothered Roosevelt, who knew that there was nothing small about black bears. Hunters had recently killed adult black bear males weighing well over 300 pounds, with short, stubby claws used to scale trees quickly. In Native American lore, so-called spirit bears—black, brown, grizzly, and polar—were all endowed with sacred characteristics; but in European culture they often had a menacing reputation, as in

Goldilocks and the Three Bears

. As a boy Roosevelt was largely unimpressed with both caricatures of bears. He wanted hard, factual, empirical data about their instinctive habits. “My own experience with bears,” he later wrote, “tends to make me lay special emphasis upon their variation of temper.”

48

The Hudson River valley was the first American wilderness area Roosevelt fell in love with. He tossed fist-sized rocks into boggy creeks and used miniature nets to scoop up minnows from local muddy bottoms. Such was his enthusiasm for the region that Roosevelt pouted the following spring when his family left for a year in Europe (from May 12, 1869, to May 25, 1870). He preferred studying North American wildlife in the woods of New York to what his parents thought would be a sweeping “continental” educational experience for their four children. Capitulating to his father’s will, Theodore put on a cheery face and grew excited about the prospect of inspecting the zoos and natural sites of old Europe. While their steamship, the

Scotia

, headed across the Atlantic, Roosevelt’s journal commented briefly on staterooms and seasickness, then focused on wild-life. Numerous entries in his log for 1869–1870—the spelling atrocious—mention some encounter or another with wildlife or domestic animals.

May 19

th

, 1869 [at sea]

Warmer. Read and played. We saw two ships one shark some fish severel gulls and the boatswain (sea bird) so named because its tail feathers are supposed to resemble the warlike spike with which a boatswain (man) is usually represented.

June 23

rd

, 1869 (London)

We went agoin to the zoological gardens. We saw some more kinds of animals not common to most menageries. We saw some ixhrinumens, little earthdog queer wolves and foxes, badgers, and racoons and rattels with queer antics. We saw two she boars and a wildcat and a caracal fight.

49

Everywhere the Roosevelts traveled in Europe, young Theodore cast a friendly eye toward living creatures. Whether it was hauling in English lake fishes with his sister Corinne or listening to the roar of a waterfall in Hastings where herons congregated, Roosevelt observed nature like a budding biologist. Even when he was touring museums or cathedrals, his eyes immediately darted toward heraldic shields with bears and bulls, statues of wooden dogs, art showing centaurs, and any scrawny stray cats that prowled territorially around the grounds as if they owned the property. Vivid descriptions of ornery mules and trotting horses populated the diaries. In “My Journal in Switzerland,” for example, Roosevelt wrote of climbing the Alps around Mont Blanc and trying to trap animals to learn “natural history from nature.”

50

Although he was bored by the manicured European botanical gardens, Roosevelt marveled on seeing his first glacier, which he anointed “Mother of Ice.”

51

While in Lugano, he was given two chameleons by the family’s carriage driver to keep as pets; he was intrigued by their uncanny ability to change colors with such ease.

52

By September 1869 the Roosevelts had made their way to southern Italy. Unfortunately, his asthmatic condition was making Theodore miserable, discoloring his face, forcing him to wheeze for air, his chest heaving and filled with mucus. Clearing his throat was necessary so often that it became a tic. Often he had to sleep sitting up in order to breathe. In his diary he cast horrific spells as awful attacks of “the asmer.” There was no effective treatment available in the mid-nineteenth century, so he suffered, gasping for air whenever flare-ups occurred. After one sick,

asthmatic afternoon, bored and bedridden, Theodore suddenly perked up at the sight of a performing canine. “In the evening a Lady came with a little dog who is the cuningest litleest fellow in the world,” he said; “he had a great many tricke letting you kiss its hand whipping you standing on its hind legs and having a dress on.”

53

Although the Roosevelts traveled through Europe in high style, young Theodore missed his tiny museum back on Twentieth Street in New York City. Discovering English birds’ nests and French snakeskins on walks, he pocketed them to haul back home for his expansive collection. Not wanting to let his natural history training lapse, he read Wood and Reid and Baird every chance he got. In Dresden, Germany, he ventured by himself to the Royal Zoological Museum, a venerable institution founded in 1728. Housing more than 100 animals, the museum had a particularly fine collection of reptiles and fishes. The main draw at the museum, however, was the intricate glass models of sea anemones precisely blown by the artist Leopold Blaschka.

54

But it was the aquarium in Berlin that really got Roosevelt’s blood running, bringing him up close to live perched ravens, rare ducks, and feisty cormorants. “We saw birds in there nests on trees and anemonese and snakes and lizards,” he recorded on October 27. “We had a walk and played chamois and after goats which I a grizzely bear tried to eat.”

55

Tellingly, even the Berlin aquarium left him missing the United States. “Perhaps when I’mm 14 I’ll go to Minnesota,” he wrote, dreaming of bird-watching in the Red River valley; “hip, hip, hurrah’hhh!”

56

In these diaries are the beginnings of Roosevelt’s imagining America as a wilderness, a mosaic of longleaf pine woods and forested wetlands, of large floodplains and swamps and lakes. Europe may have had prairies, but America had dry

and

wet prairies. To Roosevelt America had now risen in stature as a true wilderness laboratory—Europe, he sensed, was spent.

Whenever young Theodore saw animals neglected or abused, his diaries reflect his outrage. The sight of a puppy run over in a Parisian gutter sent him into a deep funk. He lamented how cows and goats were mistreated by peasants, and was upset at seeing horses suffer from whips, bits, epilepsy, frostbite, and heat exhaustion. On December 7, in Nice, he recorded how atrociously a French peasant treated his livestock. “We saw a brutal conveyance of lambs,” he wrote. “They were tied by their legs and swung across a donkeys back. We saw also a young vilain who swung a poor animal around.”

57

Three weeks later, young Theodore was horrified by the way Italians treated their animals. “It seemed as if we would never get out of Naples

which I was very anxius to do,” he wrote, “to avoid seeing the cruelty to the poor donkeys in making them draw heavey loads and nearly starving them.”

58

In Rome he bragged that “we saw a beautiful big huge dog and I was the only one he shook hands with and I am proud.”

59

Paradoxically, other entries from the same European trip extol the thrill of what hunters call the chase. Sometimes Roosevelt would patrol the streets of Rome pursuing wild dogs, cornering them so he could watch them snap and snarl up close, taunting them with his gun muzzle to provoke them to show their wolflike teeth. In prose he used dramatic imagery (indeed, clichés) about “trapping wild dogs” that were “growling furiously,” stray mongrels that “thrust into his face.”

60