The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (11 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Once the Roosevelt family left Cairo for a houseboat journey up the Nile,

*

the amount of writing T.R. produced about birds was staggering. He later stated that his “first real collecting as a student of natural history” began on this Egyptian holiday.

39

Yet he never collected a truly rare bird of scientific value.

40

The journals from this trip have titles like “Remarks on Birds,” “Ornithological Observations,” “Ornithological Record,” “Catalogue of Birds,” and “Zoological Record.” Now that they were in the Middle East, T.R.’s father gave him a French pin-fire double-barreled shotgun to use. That changed everything. Everywhere he went, his gun was close at hand. “The mechanism of the pin-fire gun was without springs and therefore could not get out of order,” Roosevelt recalled, “an important point, as my mechanical ability was nil.”

41

Although the Pyramid of Cheops enthralled him, he got a bigger thrill shooting for specimens along the riverbanks. When it came to identifying Egyptian wildlife, he put Darwin aside and instead listened carefully to the observations of local guides. Hunting with his father on December 13, T.R. shot his first bird—a warbler-like species. It was the first of thousands of birds he would kill in the name of taxidermy, science, survival and sport in the coming decades. Never before in his young life had he felt as vigorous and vital as in Egypt with shotgun in hand. Perhaps

the dry desert climate, so rehabilitating for asthmatics, helped. Every day, it seemed his spirits kept lifting. “In the morning, we passed a large flock of about sixty Egyptian geese,” Roosevelt wrote on December 29. “They were wading in the shallows, but swam out into deep water, where they arranged themselves in an irregular long line and as we approached, divided themselves into several squads and flew off in various directions. At about 12 oclock we stopped and took a walk, during which I observed no less than seven species of hawks crows, stercho finches, and small waders in easy shot.”

*

42

Even though young Theodore flourished in the desert climate, his American chauvinism didn’t dissipate as the family moved on to the Holy Land. Everything was bigger and better back home. When he arrived in Jerusalem, his first instinct was to declare it “remarkably small.”

43

Bathing in the Jordan River produced the lament that it was only “what we should call a small creek in America.”

44

To the manger of Bethlehem in Palestine, where Jesus Christ was born, T.R.’s irreverent reaction was to shoot two “very pretty little finches” for his collection.

45

Upon arriving in Damascus, the sacred ground where Paul became a disciple of Christ, Roosevelt went jackal hunting. “On we went over hills, and through gul-leys, where none but a Syrian horse could go,” Roosevelt wrote. “I gained rapidly on him and was within a few yards of him when [he] leaped over a cliff some fifteen feet high, and while I made a detour around he got in among some rocky hills where I could not get at him. I killed a large vulture afterwards.”

46

The historian Edmund Morris pointed out the jackal hunt was the future president’s first attempt to hunt wildlife for “sport, rather than science.”

47

Nothing has baffled Roosevelt scholars over the decades more than how Theodore, who vehemently opposed cruelty to animals, could nevertheless kill wildlife with such ease. Although T.R. often hunted for science (in the Middle East he was collecting for his Roosevelt Museum), one can’t escape the conclusion that he relished the thrill of the chase as a sport. Basically Roosevelt took his cues from Captain Reid in

The Boy Hunters

. The chapter “About Alligators” defended old-time naturalists like Alexander Wilson and John James Audubon against the overclassification of the laboratory school. By hunting their own specimens down, Audubon and Wilson had truly learned to understand color variations (and the eating and breeding habits) of species better than stationary

bio-lab technicians in Cambridge or New Haven. According to Captain Reid, a real naturalist lived outdoors while the “old mummy-hunters of museums” sat around like shriveled prunes making divisions and subdivisions of

Crocodilida

ad nauseam.

48

So hunting, to young Roosevelt, was a prerequisite for being a

real

faunal naturalist of the old Audubon school. But mistreating beasts of burden, who often suffered and died in streets, had nothing to do with hunting. All persons with a moral compass—as the ASPCA claimed—knew that. Also, the slaughterhouses of the world, Roosevelt complained, weren’t regulated in any way, shape, or form. Rancid meat and salmonella were commonplace. As a budding sportsman and an advocate of the humane movement, Roosevelt simply wanted hunting and the treatment of domestic animals

regulated

. Species extinction, torture of animals, overhunting, lack of seasonal bag limits, cock and bull fighting—such activities were anathema to his gentlemanly outlook on life. Killing game like cougars or bears with a knife was fine—but tormenting or teasing the animal was deemed unforgivable. Like his father and paternal grandfather, Theodore believed that animals had feelings and perhaps even communicated with one another in ways undecipherable by humans, and that they needed to be treated mercifully. By shooting finches in Egypt, for example, carefully studying their eye bands and plumage, taking careful notes of their demeanor, and lovingly stuffing them so as not to damage their plumage, Roosevelt believed he was

honoring

the species. Most other men would simply shoot birds. Roosevelt, by contrast, shot and collected them for scientific scrutiny. Only by learning everything about a species could you eventually save it from the maw of industrial man. If Roosevelt’s views pertaining to animals seem contradictory, consider this: they are essentially the hunting and animal rights codes American society abides by in the twenty-first century.

IV

When Roosevelt boarded a ship for Greece, leaving the Middle East, his asthma flared up again—perhaps returning to “civilization” made him ill. Wherever Theodore went in Europe he pouted and wheezed, believing that Greek ruins and Turkish mosques were a waste of time for an ornithologist like himself. Arriving in Vienna on April 19, 1873, he bemoaned the fact that his father needed to spend

months

in Austria on business. Young Theodore’s letters from Vienna attested to his depression: “I bought a black cock and used up all my arsenic on him.” “The last few weeks have been spent in the most dreary monotony.”

49

“If I stayed here

much longer I should spend all my money on books and birds

pour passer le temps

.”

50

While Theodore Sr. stayed in Vienna, he sent three of his children—Theodore, Corinne, and Elliott—to Dresden (known then as the Florence of the Elbe) to live with a German family. His cousins John and Maud Elliott were also there. The idea was for the American youngsters to become fully immersed in German culture. What interested the young Roosevelt most about Germany, however, were the romantic painters who had studied in Düsseldorf during the 1860s—Albert Bierstadt and George Caleb Bingham among them—and had them turned toward the American West for inspiration. And there was also his utter fascination with the white storks of Dresden, which nested in chimneys and could be found around the nearby pond. Instead of immersing himself in German history or language, he continued to play Audubon, studying the storks for variations in color and size. “My scientific pursuits cause the family a good deal of consternation,” he wrote to an aunt from Dresden. “My arsenic was confiscated and my mice thrown (with the tongs) out of the window.”

51

But something else had occurred on this Old World trip. For the first time Roosevelt had carefully read

On the Origin of Species

himself instead of being spoon-fed Darwin’s theories by an uncle, a cousin, or a adult friend. (Darwin at this time was said to be

talked

about more than

read

.) Somewhat pretentiously, catching the rising wind, Theodore now began imitating the great evolutionary theorist, talking in Darwinspeak about animal variation and natural selection, one of the basic mechanisms of evolution along with genetic drift, migration, and mutation. What was exciting about Darwin was that he was a scientist

and

an explorer; he thereby met Captain Reid’s criterion for greatness while epitomizing modernity in science. Next, Theodore read

The Descent of Man

, in which he learned that

Homo sapiens

had evolved from apes, shrews, and birds. The effect of reading these books was that Roosevelt began to sound like the character in Henry James’s

The Madonna of the Future

who breathlessly said, “Cats and monkeys—monkeys and cats—all human life is there!”

52

Roosevelt, in fact, held to Darwin’s belief that men were biological relatives of apes until his dying day.

53

More than anything else, Darwin offered the young Roosevelt the philosophy of biology. Darwin was part of the first generation ever to revolt against Aristotle’s concept of

scala naturae

, the story of a man’s march to perfection.

54

What Roosevelt grew to appreciate about Darwin was that he described geological events and natural selection in historical terms.

Evolutionists also embraced the notion that nothing was predetermined; everything was adaptive. In one swoop Darwin erased determinism from the blackboard of human collective experience. Roosevelt was not very good at physics but had a fine grasp of history. He took comfort in mathematical facts, not supernaturalism. Basically, he saw Darwin as explaining the history of the world in an orchard, a finch, a tortoise, or a desert. Darwin even offered possible answers for the extinction of the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous.

Writing to Oliver Wendell Holmes just before the 1904 presidential election (which he won), Roosevelt explained why Darwin was

the

force in the “tremendous intellectual revolution” of their time. Beaming himself thousands of years into the future, Roosevelt predicted that Darwin’s work would have an unparalleled “position in history” and that it would have been “superseded by the work of the very men to whom it pointed out the way.”

55

Roosevelt in 1873—nearly thirty years before becoming president—had already decided to become a foot soldier in the Darwinian “revolution of natural history.” Darwin had looked “with confidence to the future, to young and rising naturalists” who could understand creation from an evolutionary perspective—and he found a willing volunteer in Roosevelt. As Roosevelt later wrote, Darwin had “originality” going for him, unlike those “well meaning little creatures at universities” who were “only fit for microscopic work in the laboratory.”

56

The time had come, Darwin had said, for modern biology to lead the way toward enlightenment. “When we no longer look at an organic being as a savage looks at a ship, as something wholly beyond his comprehension,” Darwin wrote, “when we regard every production of nature as one which has had a long history; when we contemplate every complex structure and instinct as the summing up of many contrivances, each useful to the possessor, in the same way as any great mechanical invention is the summing up of the labour, the experience, the reason, and even the blunders of numerous workmen; when we thus view each organic being, how far more interesting—I speak from experience—does the study of natural history become!”

57

Careful to avoid taxonomic errors, Roosevelt began tagging the yellow wagtails and pelicans he shot. He tried to record each bird’s most minute distinguishing traits. He was particularly proud of an Egyptian plover he collected and mounted.

58

Whenever he struggled to identify and classify the birds he killed, the Reverend Alfred Charles Smith’s

The Attractions of the Nile and Its Banks, a Journal of Travel in Egypt and Nubia

would help. In fact, young Theodore’s Middle East diary marks the professionalization

of his youthful enthusiasm for wildlife and domestic animals.

59

No longer was it enough to record

seeing

“snipes” homologies were now equally important to him. The variations between the great snipe

(Gallinago media)

and the common snipe

(G. gallinago)

, for example, made all the difference in the world. The time had arrived, Roosevelt believed, for him to understand the biological reasons that some birds had nonfunctioning wings whereas hummingbirds couldn’t stop flapping theirs. “We behold the faces of nature bright with greatness,” Darwin had written, but “we forget the birds which are idly singing around us mostly live on insects or seeds, and are thus constantly destroying life; or we forget how largely these songsters, or their eggs, or their nestlings, are destroyed by birds and beasts of prey.”

60

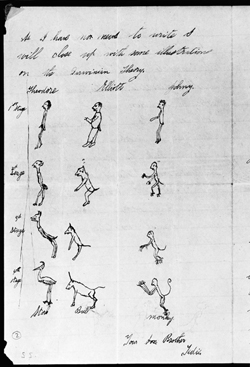

Theodore Roosevelt drew Darwinian evolutionary ideas using his family as natural selection case studies. This illustration—one of a series—was done on September 21, 1873, while he was in Dresden, Germany. He was fourteen years old.

T.R.’s Darwin evolution drawings. (

Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)