The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (83 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

The following day the

Times

announced that John Burroughs had officially accepted the president’s offer to accompany him to Yellowstone. What intrigued Burroughs most about Roosevelt was that he envinced “radical Americanism” while being a “thoroughgoing naturalist”—nobody else was doing

that

.

18

Because Oom John wouldn’t have tolerated a cougar hunt (it was supposed), the president quashed the idea altogether; he would instead act as naturalist in chief. Yellowstone’s superintendent, Major Pitcher, issued a stern statement declaring that the president’s gun would be sealed by the U.S. Army when he entered the park, just as with every other citizen.

19

In 1903 the U.S. Army, not the Department of the Interior, ran Yellowstone. “I do not know when the trip will be,” Roosevelt said, “but I think it will be just as soon as the Senate adjourns. It is doubtful whether there will be any hunting.”

20

Word that President Roosevelt was headed to Yellowstone with the famous naturalist Burroughs drew a sharp backlash from the pro-timber crowd. Governor DeForest Richards of Wyoming denounced Roosevelt as a crazy forest reserve elitist, claiming that his state would work to undermine the president at the coming national Republican convention. (Richards, however, died a few weeks later of acute kidney disease.

21

)

Westerners associated with the railroad industry never forgave Roosevelt for his conservation activism in the 1890s when the Boone and Crockett Club campaigned to make the park off-limits to commercial exploitation. But Senator Clarence Clark of Wyoming quickly came to Roosevelt’s defense: the colonel who had led a charge up San Juan Hill in the Spanish-American War would be welcome at Yellowstone anytime, night or day. “The people of Wyoming have the most implicit confidence, not only in President Roosevelt personally, but in the wisdom of his Administration,” Clark said. “They believe that he knows them, and has a personal interest in the welfare of the State.”

22

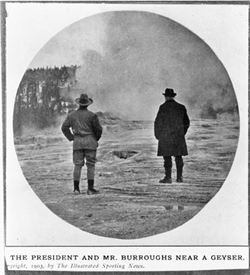

Roosevelt and Burroughs together at Yellowstone National Park.

T.R. and Burroughs near geyser. (

Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)

Even before Roosevelt’s train left Washington, the newspapers were abuzz with gossip about his working vacation. In Washington state a silly tug-of-war developed over whether the president would speak in Seattle or Tacoma.

23

By contrast, the machinists’ union in Kansas City asked that Roosevelt not come near their town, as he had done nothing in the White House to help their cause. A group of Texans lamented that Roosevelt was skipping Forth Worth and Amarillo on his way to the Grand Canyon. While Roosevelt was in Arizona, fifty Rough Riders planned to present him with a live black bear, captured in Mexico.

24

The stockmen of the Front Range of the Rockies announced that when Roosevelt’s train arrived in Hugo, Colorado, he would be greeted by 200 cowboys in full range regalia shouting “Bully!”

25

Administrators at Yosemite National

Park planned to shoot fireworks into the night sky on the president’s arrival.

26

Bored reporters took the time to calculate the impressive figures for Roosevelt’s trip: sixty-six days, 14,000 miles, averaging 212 miles a day. He would deliver more than 260 stump speeches and five major addresses. Roosevelt’s party would cross every mainland mountain range between the Poconos and the San Gabriels. “With the exception of a fortnight in the Yellowstone region and a few days in the Yosemite,” the

New York Times

noted, “he will be pretty steadily in motion.”

27

As departure day neared, Roosevelt acted like a schoolchild anticipating summer vacation. Elated about visiting twenty-five states and showing Oom John the incomparable geysers of Yellowstone, Roosevelt was the happiest he had been in years, in truly high spirits. “I am overjoyed that you can go,” Roosevelt wrote to Burroughs. “When I get to Yosemite I shall spend four days with John Muir. Much though I shall enjoy that, I shall enjoy far more spending the two weeks in the Yellowstone with you. I doubt if there is anywhere else in the world such a stretch of wild country in which the native wild animals have become so tame, and I look forward to being with you when we see the elk, antelope, and mountain sheep at close quarters. Bring pretty warm clothes, but that is all. Everything else will be provided in the park.”

28

III

Uninterested in lobbying Roosevelt for anything, Burroughs had accepted the president’s offer as a chance to better educate himself about Yellowstone and Rocky Mountain wildlife. “I had known the President several years before he became famous, and we had had some correspondence on subjects of natural history,” Burroughs wrote. “His interest in such themes is always very fresh and keen, and the main motive of his visit to the Park at this time was to see and study in its semi-domesticated condition the great game which he had so often hunted during his ranch days; and he was kind enough to think it would be an additional pleasure to see it with a nature-lover like myself. For my own part, I knew nothing about big game, but I knew there was no man in the country with whom I should so like to see it as Roosevelt.”

29

On April 1 the president’s train left Union Station with Burroughs on board, and headed for Pennsylvania’s famous Horseshoe Curve—near Altoona—in the heart of the Allegheny Mountains. Just before his departure, Roosevelt had written to Dr. Merriam of the Bureau of Biological Survey asking for up-to-date information about the Shoshones, Sioux, Hopi, Apache, and other western tribes. Roosevelt said he would be most

grateful if Merriam could put together a box of books, articles, and reports on Native Americans. The esteemed biologist quickly complied with the president’s request. Knowing that Merriam was an Indian rights activist, Roosevelt hoped to educate himself about the shabby conditions on the reservations. “In cases where you can do so without interfering with your biological survey work, I should be glad to have you secure for me reliable information concerning the present condition, necessities, and treatment by Government agents of such Reservation and non-Reservation Indians as you may meet,” Roosevelt wrote. “Show this to any Government officials as your warrant for inquiry; I shall expect them to give you all possible facilities to find out the facts deemed of interest to me.”

30

In essence Roosevelt seemed to be offering a quid pro quo to Merriam: Roosevelt’s chief biologist would provide him with pertinent information on Native Americans while he, in turn, sent status reports back to Washington, D.C., on the Yellowstone cougars, elks, and buffalo. The reports would contain no skins or claws, however: the president would not be exercising his powder finger. As Burroughs confirmed in his 1905 book

Camping and Tramping with Roosevelt

, the president refrained from hunting in or around Yellowstone, taking only field observations and photographs. That didn’t protect Burroughs from being teased by his friends. “The other night I met at dinner that fine old John Burroughs,” the novelist and editor William Dean Howells wrote to C. E. Norton that April, “whom I congratulated on his going out to Yellowstone to hold bears for the president to kill.”

31

Burroughs consistently defended Roosevelt as a naturalist first and a hunter second. “Some of our newspapers reported that the President intended to hunt in the Park,” Burroughs wrote. “A woman in Vermont wrote me, to protest against the hunting, and hoped I would teach the President to love the animals as much as I did—as if he did not love them much more, because his love is founded upon knowledge, and because they had been a part of his life. She did not know that I was then cherishing the secret hope that I might be allowed to shoot a cougar or bobcat; but this fun did not come to me. The President said, ‘I will not fire a gun in the Park; then I shall have no explanations to make.’ Yet once I did hear him say in the wilderness, ‘I feel as if I ought to keep the camp in meat. I always have.’ I regretted that he could not do so on this occasion.”

32

Chicago was a highly successful first stop for President Roosevelt on his way to Yellowstone. More than 6,000 people crammed into a downtown Chicago auditorium that had only 5,000 seats. The Halley’s comet known affectionately as Teddy Roosevelt had arrived in the flesh and the

Marconi wire was tap-tap-tapping to the world about his visit. Roosevelt passionately defended American hegemony in the Caribbean and an expanded navy, thunderous applause greeting his words.

33

To Roosevelt the Monroe Doctrine wasn’t mere diplomatic ornamentation—it was enforceable policy. He received an honorary doctorate of laws from the University of Chicago, which was rapidly becoming one of the best schools in America.

34

Afterward, Roosevelt met with a cheerful group of its students, who sang a specially composed “Dooleyized” song. One verse went:

There is a sturdy gent who is known on every hand:

His smile is like a burst of sun upon a rainy land.

He’ll bluff the Kaiser, shoot a bear, or storm a Spanish fort.

Then sigh for something else to do and write a book on sport.

35

Roosevelt’s “sport” on this Great Loop tour was conservation, not hunting. Among the primary concerns on the first leg were the devastated buffalo herds. Soon, the Bronx Zoo would have a herd to return to the prairies, and the president was shopping for a proper geographical spot. Carefully, Roosevelt inquired about the remnant herd living in Yellowstone. Working closely with Congressman Lacey, Roosevelt was eventually able to appropriate $15,000 to help manage the Yellowstone herd; the improved management included shelter buildings. With Buffalo Jones updating him on bison grazing strategies, the president grew excited about the prospect of reintroducing his Bronx Zoo herd to an experimental range in Oklahoma. If the reintroduction worked, it might be possible to create bison ranges in Kansas, Nebraska, Montana, South Dakota, and Montana.

While Roosevelt appreciated Buffalo Jones’s firsthand knowledge of bison, he believed Jones’s report on elks “was all wrong.” Jones was a self-serving old reprobate whose opinions on Yellowstone’s wildlife were usually far off base.

36

Accordingly, a determined Roosevelt tried to hand-count every elk in Yellowstone. He wanted near exact numbers. His “very careful” estimate was that there were more than 15,000 elks (a figure much higher than what Buffalo Jones was claiming). As for cougars, Roosevelt—after careful study—determined that they were actually providing a service in the park, keeping the elk herds thinned down to ideal numbers. “The cougar are their only enemies,” Roosevelt noted, “and in many places these big cats, which are quite numerous, are at this season living purely on elk, killing yearlings and an occasional cow; this does no damage; but around the hot springs the cougar are killing deer,

antelope and sheep, and in this neighborhood they should certainly be exterminated.”

37

In coming years Roosevelt would modify his harsh views about predator control in Yellowstone and elsewhere. He began seeing cougars and other predators as assets to the park’s natural balance. When word got back to the White House in 1906 that Buffalo Jones planned to hunt sixty-five cougars in Yellowstone, Roosevelt surprised Jones by nixing the idea. “I do not think anymore cougar (mountain lions) should be killed in the park,” Roosevelt wrote to the superintendent. “Game is abundant. We want to profit by what has happened in the English preserves, where it proved bad for the grouse itself to kill off all the peregrine falcons and all the other birds of prey. It may be advisable, in case the ranks of the deer and antelope right around the Springs should be too heavily killed out, to kill some of the cougar there, but in the rest of the park I certainly would not kill any of them. On the contrary, they ought to be left alone.”

38

Before leaving the White House, in 1908, Roosevelt banned the killing of cougars in Yellowstone.

39

(This didn’t stop him, however, from encouraging his sons and nephew to hunt cougars around the Grand Canyon when he was an ex-president in 1913.)

During the two spring weeks President Roosevelt was in Yellowstone, and the sheets of ice in the tree-lined rivers were cracking, he wrote a series of long reports to Merriam on how the springtime wildlife was faring. After hiking footpaths, Roosevelt made detailed zoological descriptions of antelope near Gardiner, Montana, and bighorn sheep in Yellowstone Canyon, Wyoming. As if trying to out-naturalist even Burroughs, Roosevelt made Audubonist studies of golden eagles and water ouzels. And while Roosevelt’s gun may have been locked up by the U.S. Army, nothing prevented him from collecting a meadow vole for the Biological Survey. These tiny rodents were among the world’s most fertile mammals; females were capable of producing three to ten pups every three weeks. Roosevelt, using his hat as a net, scooped one up and skinned it. Unfortunately, his arsenic can was back at Sagamore Hill. “I send you a small tribute, in the shape of a skin with the attached skull, of a

microtus [pennsylvania]

, a male, taken out of the lower geyser basin, National Park, Wyoming, April 8, 1903,” the president wrote to Merriam. “Its length, head and body, was 4.5 inches, tail to tip, 1.3 inches, of which .2 were the final hairs. The hind foot was .7 of an inch. I had nothing to put on the skin but salt.”

40