The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (79 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

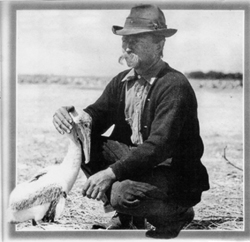

Paul Kroegel, who faced off against plume hunters in the 1900s, was a pioneer in wildlife conservation not only for Florida, but for the entire nation.

Paul Kroegel. (

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

)

Keeping vigil over birds, however, wasn’t a livelihood. As with just about all the first-generation settlers in post–Civil War Florida, Kroegel’s primary source of revenue came from farming. Besides beans, citrus groves kept the Kroegels in the black. Within eight years of moving to Sebastian—through perseverance and good seed—the Kroegels were among the most prosperous growers in Florida.

14

Sometimes, however, the citrus and bean crops couldn’t survive the deadly frost that blew in around Christmas. A single “big freeze” could cover a year’s worth of agricultural labor in an icy, deadly crust. Priding himself on beating back the frost, wrapping his trees in burlap, Kroegel defiantly grew grapefruit and oranges on his 143 acres of Indian River property when other, less determined farmers had abandoned their crop.

*

He also tended more than 100 beehives, selling his homegrown honey at a tiny roadside stand. These Florida bees weren’t transported from Europe (like those in New England) but were true “Aborigines.”

15

And scarcely a week went by when Kroegel wasn’t scything through dense hammocks to cut a trail, sometimes for extra pay and at other times just for the sake of reclamation. “Even though he had a wife and kids,” his grandson Douglas Kroegel

recalled, “it seemed it was those birds and trails he cared about the most. Even more than his kids. He was on a mission to put the bad guys [plumers] out of business on Pelican Island no matter what it took.”

16

As Kroegel approached his thirty-ninth birthday in 1903, he wondered why the federal government wasn’t stopping the massacre of these Pelican Island birds. After all, Washington, D.C., owned the island and half a dozen adjacent smaller keys in Indian River. Didn’t the Lacey Act prohibit such reckless slaughter? Couldn’t the Roosevelt administration ban it on federal property? Shouldn’t the new law against killing pelicans be enforced as the one in Chemnitz was for storks? Wouldn’t it be smart to create a bird reserve? Just asking these questions made Kroegel an irregular character in the fishing community of Sebastian. With his steely gaze, huge droopy mustache, and blistered boatbuilder’s hands, Kroegel, a father of two, cut an imposing figure for a man only five feet six inches tall. His round face had developed a network of wrinkles, accentuated by a deep year-round tan. Uninterested in clothes, Kroegel often wore heavy wool garments (including sweaters) and Sunday serge in the torrid sun to avoid being “eaten alive” by mosquitoes, which were also considered potential carriers of malaria.

17

He often carried an accordion with him to play at weddings and anniversary parties. To the Indian River fishermen in search of juvenile snappers and snook, the pipe-smoking Kroegel was a misanthrope of sorts. Sebastian back then had something of a Jamaican tang. The air smelled of seaweed, freshwater catch, guano, and horse dung. Local seafarers and dirt farmers sat around with basins of fish in the heat, repairing nets; they ostracized Kroegel for being so indignant about plume hunters bagging egrets and gunning down the fish-stealing pelicans which roosted and nested as thick as bats on the treeless Pelican Island rookery.

Like Audubon—who had tramped around the Gulf’s southern tidal swamps—Kroegel would get a careful fix on each bird’s unique temperament, silently crawling up close to measure habits such as skittishness, sociability, and cunning. Colonial waterbirds preferred to nest in colonies, grouping closely together for protection from predators. They particularly liked nesting on thick mangrove clumps, where they could easily glance around every inch of the rookery and sound a choir-like alarm if a predator was approaching. So on any given day Kroegel saw herons mingling with pelicans while spoonbills clustered only two or three feet away. As a dreamer—unschooled in ornithology—he imagined this patch of Florida as a northward extension of the tropics, and that idea invigorated him. But owing to guano buildup and “big freezes,” particularly the

horrific freezes of December 1894 and February 1895, many of the mangroves on Pelican Island had died. With no other options, the birds took to constructing their nests on the ground. Kroegel dutifully recorded in a notebook how this change in nesting affected their hunting habits. But whether the birds were perched high or nesting low, pelican sightings on his beloved islet brought him happiness.

Besides studying birds and farming, Kroegel was a boat builder par excellence. Schooners, skiffs, tall-masted sailboats, yachts, collapsible canoes—he constructed them all. Before long his expertise outclassed that of any other Floridian living within a thirty-mile radius of Sebastian and Wabasso.

18

With no major roads in the sandy-soil Sebastian area, save a few heavily rutted swampy paths, boating in the Indian River was still the main mode of transportation as the nineteenth century wound down.

*

Whenever a fierce wind blew off the Atlantic coast, the people of Sebastian—even those who thought Kroegel’s bird-watching too eccentric—were in full agreement that his boats were sure to survive the coming tempest. His exemplary vessels were—without question—the epitome of nautical craftsmanship. Whenever there was a shipwreck in the Atlantic Ocean—like that of the

Mary Morse

in September 1898—Kroegel would rush out to assist the stranded crew. (In that particular disaster he earned $350 for salvaging the cargo of lumber planks.) Meanwhile, Kroegel had studied hard to earn his captain’s papers from the state at age twenty; he was thereafter known as “Captain Paul.”19

Navigating the shallow Indian River Lagoon—still, according to the Audubon Society, considered the most biologically diverse estuary in America

20

—had become second nature to Kroegel, as much a part of his daily regime as eating, sleeping, and oystering. Kroegel went out patrolling the Indian River Lagoon at midday, when the invigorating ocean breezes brought wind for his sailboat and welcome relief from pesky sand flies and mosquitoes. Salt marshes with the associated mudflats and tidal creeks provided a wealth of food and habitats for fiddler crabs, marsh rabbits, and wading birds. Self-trained in natural history, Kroegel could tell the difference between smooth cordgrass, saltwort, and glasswort at a glance. At nighttime, starlight and the phosphorescence of more than 250 algae species were his illumination as he rowed passed sorrowing cypress.

Starting in 1902, the Florida Audubon Society paid Kroegel a meager

wage to patrol the Indian River Lagoon for plumers. He was a conservationist gatekeeper. With his .10-gauge double-barrel shotgun always close at hand, ready to aim, Kroegel was determined to save the approximately 3,000 brown pelicans on Pelican Island from the barbarians. With his sailboat weaving about in a sort of hurried dance, Kroegel began patrolling the lagoon, threatening anybody who dared to disrupt his Indian River rookery. The worst offenders were thugs who sneaked onto the island under cover of darkness. Because the channel was so narrow, all large vessels going up and down the river had to pass within a scant 100 feet of Pelican Island, keeping Kroegel busy. If a boat dared anchor near the island, off Kroegel went, like an arrow shot from a pulled bow.

21

According to family lore, Kroegel slept with one eye open; that’s how seriously he took his wildlife protection job.

III

Like Paul Kroegel, and other grassroots activists, Roosevelt had become disgusted that hunters in Florida would shoot a beautiful roseate spoonbill—to name just one species—so unscrupulous shops could sell its gorgeous wings as cooling fans to “snowbird” tourists in Miami and style-conscious debutantes in New York and Paris. Long ago Roosevelt had read about William Bartham’s travels through wild Florida in the 1790s, and he wanted patches preserved just as that great seventeenth-century naturalist had encountered them at Alachua Savanna and along the Saint Johns River. Intellectually, Roosevelt was uninterested in compromises and in sidestepping conservation issues. When it came to protecting Florida’s endangered wildlife, he was determined to choke the breath from the renegade plumers’s business. He wanted the Lacey Act followed to the letter of the law. The Roosevelt administration’s threat as of early 1903 was serious: shoot a protected nongame bird; go to jail.

In some ways Roosevelt and Kroegel shared many of the plumers’ rough-and-ready Jacksonian attributes. Unhappy away from the outdoors, enamored of even the minutest habits of animal species, they prided themselves on their ability to track down wildlife by hunch and hoof-print. They were both a new breed of outdoorsman who preached wild-life protection.

22

Essentially, Kroegel embodied the new Rooseveltian high-water mark in conservation history: the insistence that wildlife had rights. Emulating the naturalist John Muir—who in 1867 had tramped all over Florida, marveling in his journal that the state’s wide rivers did “not appear to be traveling at all”—Kroegel lived to protect “citizen bird.”

23

Although Kroegel had never met the president, he knew many

of Roosevelt’s naturalist friends, and fancied himself as part of their clique.

This, in fact, was another striking characteristic that made Kroegel sui generis in the Indian River Lagoon area: his uncanny ability to cultivate enduring friendships with a wide array of national wildlife protection leaders. Never formally trained as an ornithologist, he nevertheless enjoyed bantering about shorebirds and was up-to-speed on the cutting-edge

Auk

articles of his day. Of the many friendships he formed protecting Pelican Island, one proved life-changing: his encounter in 1900 with Frank M. Chapman, curator of ornithology and mammalogy at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

By the 1880s Chapman—whose mother spent winters in Gainesville at a family cottage near what is today the University of Florida—was considered America’s most prominent popular ornithologist. When Chapman first visited his mother as a young man in his twenties—just after publishing his

Handbook of Birds in Eastern North America

—he made a long “local list” of the hundreds of birds he encountered in north central Florida, as if he were maintaining a sacred scroll. As a complement, Chapman kept a journal of his chance encounters with long-necked ducks, purple gallinules, and a wide range of ibises. Then he had the central, transformative ornithological experience of his life. One Sunday afternoon shortly after Thanksgiving 1886, while hiking in the pinelands around Alachua Lake, he happened upon an idyllic scene that nearly took his breath away. All around him were magnificent birds behaving in an almost magical fashion. Dutifully, he recorded in his diary what he had encountered that November day:

As I approached the shore numbers of Ducks arose and sought safety in the yellow pond lilies (bonnets) growing some distance from it, and here was a splashing and a calling, a squeaking and squawking, such as I never heard before: odd noises of all sorts and descriptions all unknown to me, and I was without both gun and glass. The place seemed to be alive with birds. Ducks were constantly flying from place to place; coots and Herons were apparently common. On the shore near me birds were just as abundant. A pair of Pileated Woodpeckers, with flaming crests, were pounding away in a tree above my head, and with them were numbers of Flickers, and one Red-bellied Woodpecker. Doves whistled through the woods at my approach, Blue Jays screamed, Mockers chirped, and scores of birds flew from tree to tree. Truly I was in an ornithologist’s paradise.

24

What Chapman had stumbled upon was a patch of pristine Florida. For a budding New York ornithologist it was something akin to a fortune seeker stumbling upon a pile of gold. There, before his eyes, was an embodiment of divine law. At once Chapman started collecting Florida’s birds—he shot 581 different ones, to be exact—for the American Museum of Natural History in New York. He always wanted the United States to be a step ahead of the British Museum when it came to ornithological studies. If his conscience bothered him at the sight of torn flesh and flying feathers—and it occasionally did—Chapman just blamed the birds’ death on the necessities of modern science. All he could do in good conscience was avoid defacing the dead birds’ exotic splendor any more than absolutely necessary when skinning. Meanwhile, Chapman—considered

the

supreme authority on Florida’s birds—began exploring new ways for ornithologists to work without guns, using cameras and binoculars.

By the time Roosevelt became president Chapman’s advocacy for “citizen bird” found a literary outlet in a revolutionary little book, which tried to turn the “sportsman’s ethos” on its head. That year Chapman published

Bird Studies with a Camera

, complete with more than 100 photographs taken by the author himself. This was the kind of evolved birding that Roosevelt approved of—take a photo of the brown pelicans or herons and leave your gun at home. It anticipated eco-tourism and international birding. What Chapman had attempted to do—and by and large succeeded in doing—was to use his camera as “an aid in depicting the life histories of birds.” Sometimes, instead of merely photographing a chickadee at a nest hole or young herons on branches seventy feet from the ground, Chapman would also capture images of their habitat—an application of his philosophy regarding museum displays. “A photograph of a marsh or woods showing the favorite haunts of a species,” Chapman wrote, “is worth more than pages of description.”

25