The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (89 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Over time botany became Muir’s passion. In 1863 he took his first botanical tramp along the Wisconsin River to the upper Mississippi River. Hunting for plants liberated him from religious orthodoxy and family commitments. He drifted to Ontario, Canada, working for a long spell at a sawmill and a broom and rake factory. In Ontario he discovered the rare orchid

Calypso borealis

(this led to his first published article in the

Boston Recorder

). Odd jobs became Muir’s specialty: they were his way to finance his botanical tramps. In 1867, however, a factory accident made Muir temporarily blind. When his vision returned, he made a vow to himself: he would dedicate his life to nature (“the University of the Wilderness,” as

he called it). Off he went on a 1,000-mile walk to the Gulf of Mexico and Florida (with South America his eventual destination). When a bout of fever prevented him from tramping south of the Tropic of Cancer, he contemplated the relationship between man and nature in new and profound ways while his temperature soared to over 100 degrees. Like Roosevelt, Muir concluded that all species have an inherent value and a right to exist. Not until 1911, however, would Muir fulfill his dream of exploring the Amazon of Brazil and the mountains of Chile.

Muir’s arrival to San Francisco in 1868 forever changed his life. From April to June, he hiked around Yosemite. Walled in by the Sierra range, Muir was captivated by the enduring rocks, slow-moving glaciers, and ancient redwoods, which Yosemite offered up in astonishing numbers. There was a grace to Yosemite which defied language; it was a terrestrial manifestation of the Almighty. There was no denominational snobbishness and no chosen people in nature; there was just one big sky. “His studies in the Sierra, earnestly as they were pursued, were only secondary—his rapt admiration of the dawn and the alpenglow, of majestic trees that wave and pray, of rejoicing waters, and the sacred, history-bearing rocks, of night and the stars on lonely mountain tops,” Clara Barrus wrote in an article for

The Craftsman

, “reveal the soul of the mystic.”

111

From 1869 on, Muir’s almost wanderlust life was framed by holy Yosemite: making his first ascent of Cathedral Peak; taking Ralph Waldo Emerson to see the great falls; publishing his first article in California on glaciers; and articulating the wilderness protection ethos in

Century

magazine. In between there were all sorts of fine outdoor adventures ranging from climbing Mount Shasta (14,400 feet) to floating 200 miles down the Sacramento River. But somehow he always came back to holy Yosemite. Muir’s discoveries in Alaska, his promotion of U.S. national parks like General Grant and Sequoia, and his creation of the Sierra Club in 1892 brought him much celebrity back east. He became wild California personified to the New York literary set. When Muir published his first book in 1894—

The Mountains of California

—he became widely known as the “sage of the Sierras,” the West Coast counterpart of John Burroughs. Before long he was writing so much high-quality prose that the term “Muirian” came into academic use.

112

From the outset, there was much Roosevelt admired about Muir. Although Muir sometimes played the misanthrope, he had a shrewd political instinct. Memories of Yosemite seemed to gush out of Muir once back in the San Francisco Bay area. “Ordinarily, the man who loves the woods and the mountains, the trees, the flowers, and the wild things, has in him

some indefinable quality of charm which appeals even to those sons of civilization who care for little outside of paved streets and brick walls,” Roosevelt wrote. “John Muir was a fine illustration of this rule…. His was a dauntless soul, and also one brimming over with friendliness and kindliness.”

113

Not only did Muir write as naturalist with the authority of someone like Thoreau or Burroughs; he also joined the U.S. Forestry Commission, offering practical advice on land management. He could play the wonk when necessary. Muir’s articles in

Harper’s Weekly

and

Atlantic Monthly

galvanized popular support for protecting forests. Although history always associates Muir with Yosemite, he was also largely responsible for Mount Rainer’s becoming a national park in 1899. So when Roosevelt arrived in Muir’s backyard, Yosemite National Park, in 1903 the sixty-five-year-old Muir was celebrated worldwide as a wise man. That year alone, and the next, Muir traveled to London, Paris, Berlin, Russia, Finland, Korea, Japan, China, India, Egypt, Ceylon, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Hawaii. Roosevelt had purposefully come to Yosemite before Muir left on his intercontinental tour. The president wanted to pay homage to Muir (and to exploit their high-profile rapport for the history books).

The general goodwill between Roosevelt and Muir that spring was

exemplary. Both men had gone after the “malefactors of great wealth” in the West for raping the natural landscape. Muir was thrilled that President Roosevelt—through Secretary of the Interior Hitchcock—was punishing those who abused their power at the GLO (and even forcing the commissioner Binger Hermann to resign in disgrace for covering up the Halsinger Report regarding land fraud in Arizona). Directing Hitchcock to investigate illegal land grabbers such as John A. Benson and Frederick A. Hyde (two lawyers in San Francisco whom Muir deeply distrusted), President Roosevelt waged “historic warfare” against dishonest California cooper syndicates, real estate speculators, thieves at the land office, and lumber companies. Under Roosevelt’s influence the county indicted Binger Hermann, Senator Mitchell of Oregon, and Benson and Hyde. In other words, besides their insatiable love for the outdoors, Roosevelt and Muir shared enemies lists.

114

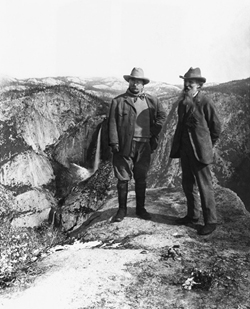

Roosevelt and Muir in Yosemite National Park.

T.R. and Muir at Yosemite National Park.

(Courtesy of the Sierra Club)

The great three-night Yosemite campout of Roosevelt and Muir almost didn’t happen, owing to conflicting schedules. As noted Muir had planned to travel around the world promoting national parks with his conservationist friend Charles S. Sargent that May. But Roosevelt, upon hearing of this, sent Muir a coaxing personal letter. “I do not want anyone with me but you,” he wrote, “and I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you.”

115

Realizing that such private time with the president discussing vulnerable Yosemite would be invaluable to the preservationist movement, Muir wiggled out of his other commitment. “I might be able to do some good in talking freely around the campfire,” Muir told Sargent apologetically.

116

As difficult decisions go, Muir was right to postpone his globe-trotting to spend this time with Roosevelt. Roosevelt and Muir, in the temple of Yosemite, vowed to let their biographies be intertwined for the sake of the conservation movement they were both leading, each in his own way. In effect, the Sierra Club joined forces with the Boone and Crockett Club—hikers and hunters forged an alliance on behalf of California’s preservation. Always a biosphere activist, Muir talked nonstop with Roosevelt about the Sierra Club’s ambition to get the Yosemite Valley incorporated into the surrounding park. And his stories of reckless timber depredations were ideal for arousing Roosevelt to shout down the “swine”—his new favorite word. Muir proved masterful at riling Roosevelt up. “I stuffed him pretty well regarding the timber thieves,” Muir later bragged to a friend, “and the destructive work of the lumbermen, and other spoilers of the forests.” As for Roosevelt, he admired Muir’s dedication to California’s beauty. Muir, he knew, was a hero and

a live wire when it came to preserving Yosemite; Muir spoke directly and from the heart at all times. At one point, by the campfire, Roosevelt began telling his yarns about big game hunting. Muir, however, was bored and was singularly unimpressed. “Mr. Roosevelt,” he asked, “when are you going to get beyond the boyishness of killing things…. Are you not getting far enough along to leave that off?” After a moment’s pause Roosevelt, in a softer voice than usual, replied, “Muir, I guess you are right.”

117

(But while Roosevelt did start promoting the camera instead of the rifle, he never gave up the sport of shooting big game.)

Because Muir was

the

California mountain man, Roosevelt embraced him as a fellow advocate of the strenuous life. Muir’s philosophical concept of God as being found in nature likewise earned Roosevelt’s approval. They were joined at the hip in both regards. But Roosevelt was truly at odds with Muir over sport hunting. When Muir, for example, received a solicitation to support a society called the Sons of Daniel Boone (which was like the Boy Scouts), he demurred. Young Americans, Muir wrote, needed to mature away from “natural hunting blood-loving savagery into natural sympathy with all our fellow mortals—plants and animals as well as men.” And this wasn’t an isolated antihunting statement. Muir’s correspondence after 1903 is laden with criticisms of “the murder business of hunting,” and with demands that the “rights of animals” be enforced as ethical standards. This was a far cry from Roosevelt’s and Burroughs’s belief that sportsmanlike hunting and fishing provided “ideal training for manhood” and would in the end “save the nation” from effeminacy.

118

Hunting wasn’t the only intellectual division between Roosevelt and Muir. Roosevelt liked Gifford Pinchot too much for Muir’s comfort. Ever since the dispute in Portland Muir saw Pinchot as—for the most part—a deadly enemy. Muir didn’t recognize the Pinchot who helped save wonders like Crater Lake or Wind Cave; he saw only a featureless scoundrel who had once said that forests were a factory for trees.

119

And soon to come was Muir’s tragic disagreement with Pinchot over Hetch Hetchy—the glacial valley filled by the Tuolumne River in 1923 with the construction of the O’Shaughnessy Dam. Why didn’t Roosevelt use an executive order to save Hetch Hetchy? Still, some historians have mistakenly downplayed Roosevelt and Muir’s mutual admiration society. There was a very real tenderness between them. Ever since Muir formed the Sierra Club in 1892, Roosevelt had kept a close eye on his courageous actions; Roosevelt was, in fact, a New York cheerleader for Muir. While Roosevelt always saw Ulysses S. Grant as the “father of the national parks,” he knew that Muir was California’s watchdog. In particular Roosevelt’s famous essay “Wil

derness Reserves” echoes Muir’s 1901 book,

Our National Parks

. However, Roosevelt was disappointed that unlike Burroughs, Muir simply didn’t know his birds; he was focused on “the trees and the flowers and the cliffs.”

120

Because Roosevelt considered himself “many-sided” he unhesitatingly and admiringly accepted Muir’s self-description as a Californian “poetico-trampo-geologist-bot. and ornith-natural, etc!—etc!—etc!”

121

By 2009 the John Muir National Historic Site had created a Web site featuring dozens of “Muirisms” arranged alphabetically. Whether you looked under “Age” or “Rough It” or “Water Ouzel,” all of these pearls of wisdom

could

have been written by Roosevelt; their viewpoints on nature were that closely shared. With great enthusiasm, Roosevelt read Muir, savoring lines like: “Any glimpse into the life of an animal quickens our own and makes it so much the larger and better every way.”

122

And Muir wrote to his wife that Roosevelt was “so interesting,” overflowing with “hearty & manly” companionship.

123

“Camping with the president was a remarkable experience,” Muir told Merriam. “I fairly fell in love with him.”

124

Oh, what a grand time Roosevelt and Muir had together in Yosemite for those three memorable days. They hiked to and camped in many of the most beautiful spots in Yosemite, including Bridal Veil Falls, where they had a fantastic view of El Capitan and Ribbon Falls gushing down from the valley’s north rim. Religious metaphors filled Roosevelt’s writings about Yosemite, with Muir serving as his Old Testament guide through the wilderness. (Except that Muir’s god wasn’t the god of ancient Israel.) For starters, there didn’t seem to be a sickly face within 100 miles of the park; such human healthiness always appealed to Roosevelt. Even though Yosemite was a national park, bear traps were still laid on the floor of Yosemite Valley; Roosevelt wanted the “setters” arrested. Only hunting bears with rifle or knife was a sport; there should be no steel traps in a national park.

125

Although Roosevelt changed clothes a few times, he is remembered as wearing jodhpurs with puttees, a thick sweater, a Stetson hat, and around his neck a soiled bandanna. Muir wore an oversize coat and loose-fitting trousers, looking rather like a hobo who had been cleaned up for a photo. Both men later boasted that they were alone in the Sierras, but Leidig and Lenord were constantly with them. There were also two packers and three mules.

Housed in the Yosemite National Park Archive is a detailed report of Roosevelt and Muir’s visit of 1903, written by Charlie Leidig, one of the trail guides. It gives a revelatory

insider’s

look at the trip. Leidig, for ex

ample, claimed that Roosevelt was annoyed when Muir wanted to stick a twig in one of the president’s buttonholes. He also noted that “some difficulty was encountered because both men wanted to do all the talking.” According to Leidig the president snored loudly, mimicked birds exactly, ate huge amounts of steak-fried chicken, and disdained crowds. Roosevelt’s primary order was to “outskirt and keep away from civilization.”

126

Highlights, according to Leidig, included seeing the sonorous Bridal Veil Falls, or

Pohono

(“puffing wind”), as the Indians called them.

127