The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (90 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Roosevelt complained that the botanist and ornithologist Muir was much more interested in the trees than in the deer families they encountered along the primitive trail.

128

Muir explained to Roosevelt on the third day, May 17, that he had an ulterior motive, an agenda item—saving Mount Shasta along the California-Oregon border and enlarging Yosemite National Park to include Mariposa Grove at the Yosemite Valley. Roosevelt was all ears, enjoying himself in the timeless hills and valleys of Yosemite. Always intent on self-mythologizing, Roosevelt had created a “lost in the wild” scenario for himself. It made for good copy. There was something very romantic, indeed, about the president of the United States sleeping outside in a snowstorm, high in the Sierras, with the weather-worn John Muir as a companion. At sunrise Roosevelt and Muir hiked into Yosemite Valley, camping within range of the spray from Bridal Veil Falls. “John Muir talked even better than he wrote,” Roosevelt found out in Yosemite. “His greatest influence was always upon those who were brought into personal contact with him.”

129

Back at the Sentinel Hotel, still pumped up with adrenaline, Roosevelt was unbelievably buoyant. He portrayed himself as a surviving backwoodsman, trapped by the harsh winter, eating dusty bread. “We were in a snowstorm last night, and it was just what I wanted,” he said. “This is the one day of my life and one that I will always remember with pleasure. Just think of where I was last night. Up there!” President Benjamin Wheeler of the University of California–Berkeley hosted a dinner for Roosevelt at the Sentinel Hotel in the park. Instead of speechifying, Roosevelt recounted his exploits with Muir on Glacier Point “amid the pines and the silver firs in Sierrian solitude, in a snowstorm, too, and without a tent.” Again he declared, “I passed one of the most pleasant nights of my life. It was so reviving to be so close to nature in this magnificent forest of yours.”

Muir had been a wise, shrewd host. His desired effect had been to galvanize President Roosevelt to save more of wild California from human

destruction. The camping in Yosemite clearly worked. Back in Washington, D.C., Roosevelt urged Congress to bring as many California redwoods as possible into the national park system. He wanted both the Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove to be part of the Yosemite National Park (at the time, they weren’t). Immediately after leaving Yosemite, while he was in Sacramento, Roosevelt fired off a telegram to Secretary of the Interior Hitchcock. “I should like to have an extension of the forest reserves to include the California forests throughout the Mount Shasta region and its extensions. Will you not consult Pinchot about this and have the orders prepared?”

130

No sooner had Roosevelt sent the order saving the Mount Shasta region than he wrote Muir a thank-you letter; he was already missing Muir’s companionship and merry blue eyes. They had achieved a feeling of brotherhood. “I trust I need not tell you, my dear sir, how happy were the days in Yellowstone I owed to you, and how greatly I appreciated them,” he wrote. “I shall never forget our three camps; the first in the solemn temple of the giant sequoias; the next in the snowstorm among the silver firs near the brink of the cliff; and the third on the floor of the Yosemite, in the open valley, fronting the stupendous rocky mass of El Capitan, with the falls thundering in the distance on either hand.”

131

Attached to this letter was his telegram to Hitchcock.

In Sacramento, still full of his Yosemite experience, Roosevelt also spoke publicly on behalf of the Muirian vision of California. Some Californians had demonized Muir as a “fanatic” or “cold-hearted crusader who cared too much for nature and too little for humans”—but Roosevelt was now a defender of the Sierra Club.

132

“Lying out at night under the giant sequoias had been like lying in a temple built by no hand of man, a temple grander than any human architect could by any possibility build, and I hope for the preservation of the groves of giant trees simply because it would be a shame to our civilization to let them disappear,” he said. “They are monuments in themselves…. In California I am impressed by how great the State is, but I am even more impressed by the immensely greater greatness that lies in the future, and I ask that your marvelous natural resources be handed on unimpaired to your posterity. We are not building this country of ours for a day. It is to last through the ages.”

133

VIII

Sacramento wasn’t a very impressive city after Yosemite. It was all dull buildings and mud holes, surrounded by impressive trees. As scheduled, Roosevelt delivered a few speeches in a high clear voice. In Sacramento, at

the state capitol, men were wearing wingtips instead of buckskin boots. On leaving Sacramento Roosevelt headed straight to Mount Shasta—known as the “glorious sentinel of the Northern Gateway to California’s flowery glades”—which was shrouded in clouds.

134

Rising upward like a mysterious fortress of oneness overlooking the surrounding Klamath Basin terrain, lonely Mount Shasta was seemingly unconnected to any range.

135

The beat poets Jack Kerouac, Lew Welch, and Gary Snyder would later describe Shasta, in cloud and sunshine, as if it were an embodiment of Zen, or California’s Fuji. The memory of Shasta stuck in Roosevelt’s mind for years to come. The artist Harry Cassie Best, hearing of the president’s adulation of Shasta, presented Roosevelt with a realist painting of the snow-clad monarch bathed in eloquent pinks, subdued oranges, and rose-misted purples. The talented Best was able to depict reflected light in the British tradition of J. M. W. Turner. “I appreciate very much your painting, the ‘Afterglow on Mount Shasta,’” Roosevelt wrote to Best, “and shall give it a place of honor in my home. I consider the evening twilight on Mt. Shasta one of the grandest sights I have ever witnessed.”

136

With President Roosevelt’s help many of Best’s paintings of California ended up hanging at the Cosmos Club.

137

In Oregon the president’s train headed to the downtown Portland depot, where 20,000 people had come to witness the laying of a cornerstone for a Lewis and Clark Memorial. For hours Roosevelt put his forefinger to the brim of his Stetson instead of shaking all those hands. As always, he was courtly to the women. Roosevelt was able to see the Columbia and Willamette rivers and Mount Hood, but he never made it to Crater Lake, which was too far off the rail line. William Gladstone Steel—called the father of Oregon’s first national park—was in the audience for the ceremony at the Lewis and Clark Memorial but was apparently not formally introduced to the president.

138

In Portland, Roosevelt did meet with the wildlife photographer William L. Finley, the William Dutcher of the Pacific Northwest. It was probably refreshing for Roosevelt to use Linnaean binomials in speaking with Finley; neither Muir nor Burroughs often used these terms, because they seemed pretentious.

139

According to Finley, while Roosevelt had been in the West more than 120 tons of killed wild ducks had been shipped to San Francisco from Oregon; they were a popular dish in the city’s booming restaurants. Finley desperately wanted to enact an Oregon model bird law to halt such slaughter. With admirable persistence he was keeping vigilant watch over Oregon’s bird population, protecting even old dead stumps because flickers used them as homes.

140

Plume hunting was as

horrific in Oregon as in Florida—maybe worse. Millions of Oregon’s birds were being slaughtered for this purpose, from Portland to the Klamath Basin.

As a boy growing up in Oregon, Finley had collected bird skins and practiced taxidermy. But in 1899 he became an Auduboner, enamored of the Cascades and intruigued by the mysteries of flight. Then the Pacific Ocean beckoned him. His life mission was now to photograph Oregon’s terns, puffins, grebes, and enormous winged pelicans, partly as a form of public relations (to help put the milliners out of business) and partly as an artistic endeavor. Encouraged by the fact that Steele had gotten his Crater Lake National Park from Roosevelt and Pinchot in 1902, Finley, with some advice from Frank M. Chapman, formed a chapter of the National Association of Audubon Societies in Oregon. And along with the photographer Herman Bohlman, Finley began playing the role of “Chapman with Kodak” along the Oregon coast near Tillamook Bay. They had been inspired, in part, by Chapman’s revolutionary

Bird Studies with Camera

. Finley’s images are now considered pioneering wildlife photography gems; they inspired

National Geographic

to improve its approach to capturing birds up close, even hatching. Finley was part of the first generation to abandon “shoot-skin-record” ornithology in favor of the camera.

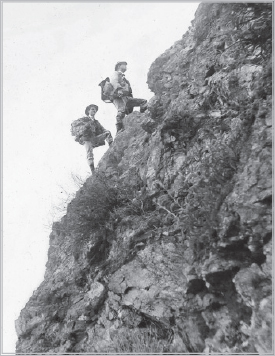

William Finley and Herman Bohlman climbing Three Arch Rock. Together they photographed birds all along the Oregon coast and Klamath Basin.

Finley and Bohlman. (

Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

)

There is no transcription of Roosevelt and Finley’s meeting in Portland. Supposedly, Finley showed the president photographic images of Tillamook Bay’s bird life (eventually included in his

American Birds

, published in 1907). The genius of Finley (with assistance from Bohlman) was that he’d climb any trees, even wobbly Douglas firs or tilted cedars, to photograph the nests of western tanagers and common bushtits. He was always searching for nature’s fair light. Clean-shaven, elegantly slender, with a wild exaltation in his eyes, Finley became perhaps the best ornithologist the Pacific Northwest ever produced. He used ladders, lanterns, ropes, grapnels, rafts, glass plates, tripods, dories, and canoes as the tools of his trade, and no part of nature was off limits to his ingenuity. When camping on the beach, Finley explained, he “reached a sort of amphibian state.”

141

Since the creation of Pelican Island in Florida as a federal bird reservation in March 1903, West Coast ornithologists writing for

The Condor

began telling Roosevelt about Pacific Ocean “bird rocks” that should become refuges. Finley was no different. He wanted Three Arch Rocks—three huge, surf-hammered rocks (plus six smaller ones) half a mile offshore from the town of Oceanside, Oregon—to become the first national wild-life refuge on the Pacific Coast.

142

The three principal rocks had arches carved by the wind and waves, making for a dramatic oceanic landmark. Besides their inherent tourist appeal, the rocks were home to Oregon’s largest nesting colony of seabirds, and Finley had tried to scientifically document all the varied avian activity there in 1901. As Finley’s photographs showed, there were 200,000 nesting common murres on Three Arch Rocks, making this the largest species colony south of Alaska Bay. Pigeon guillemots, rhinoceros auklets, and glaucous-winged and western gulls also came to the rocks. Unfortunately, so too did San Francisco restaurateurs, who raided Three Arch Rocks. In addition, this site was the

only

breeding ground for Steller sea lions on Oregon’s coast.

143

Finley and Bohlman wanted immediate federal bird reservation status for Three Arch Rocks. By documenting the Oregon Coast in peril these wildlife photographers rendered a great service to the country. Three Arch Rocks eventually became an iconic site: decades later American Airlines used as its primary travel image a gorgeous color photograph of the arches, reproducing the picture on check-in screens and in flight magazines.

Pressed for time in Portland, Roosevelt graciously invited Finley to the White House to make a formal presentation of wildlife sites in Oregon and Washington that needed preserving in the near future. Just as Roosevelt

had a weak spot for white and brown pelicans, he also had a joyful infatuation with tufted puffins, cute-looking alcids that congregated in large numbers—between 2,000 and 4,000 at a time—on Three Arch Rocks.

By the time Roosevelt left Portland, Finley knew he had a new ally. In the coming years Finley, in collaboration with Bohlman, developed more than 50,000 still nature photographs of the Pacific Coast.

144

And in the summer of 1903, inspired by Roosevelt’s policies, Finley and Bohlman literally lived on Three Arch Rocks, determined to capture bird life on film and eventually bring the images to the White House. Fate had done Oregon an immense favor by bringing Finley and Roosevelt together. Meeting Roosevelt transformed Finley from a wildlife photographer to a wilderness warrior. Just a few weeks after meeting T.R. in Portland, Finley went after the operators of the tugboat

Vosberg

, which used to dock in Tillamook Bay, taking passengers on Sunday shooting sprees along the bird rocks. It was slaughter simply for recreation. “The beaches at Oceanside were littered with dead birds,” Finley told the Oregon Audubon Society, “following the Sunday carnage.”

145

Armed with the “model bird law,” Finley was able to put the

Vosberg

out of business. Furthermore, Finley, using his Rooseveltian alliance with AOU’s William Dutcher to Oregon’s benefit, arranged for two wardens to be hired with Thayer Fund money in the Klamath Basin. On being elected president of the Oregon Audubon Society in 1906, Finley bought a patrol boat to police the Klamath Basin wetlands against milliners. His commitment to “citizen bird” was total. In a public relations stunt aimed at exposing feather hunting as immoral, Finley tore a plumed hat off a prostitute in Portland, causing bedlam on the street, which local newspapers reported in vivid detail.

146

It was free publicity for the Audubon movement. And Finley also assisted the Roosevelt administration in going after the crooked Senator John Hipple Mitchell’s illegal coastal land deals.

*

147