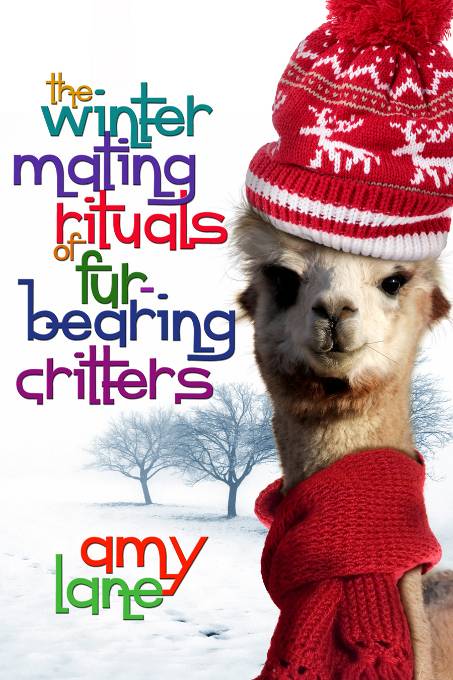

The Winter Courtship Rituals of Fur-Bearing Critters

Read The Winter Courtship Rituals of Fur-Bearing Critters Online

Authors: Amy Lane

This one’s for John and his husband, Andrew.

Andrew spins, John knits, and together,

they warm the hearts of everyone who knows them.

Chapter 1

Bald

Crawford watched the new resident of #15 Llama Lane move in with interest. It was early September in Granby, Colorado, and the snows were not that far off.

Granby, Colorado, part of Grand County, sat in a bowl of a valley which was, itself, set shallow in the midst of the peaks of the Rocky Mountains. According to the computer, it was a mere thirty-four miles away from the more populous Fort Collins, but that thirty-four miles was over a road so treacherous and so winding that they had made it a state park. From June to August, people from all over the world traveled over Trail Ridge Road (otherwise known as Highway 34) in awe. For one thing, it made it to over 12,000 feet in elevation, making it the highest road in the country. For another, it still had six feet of snow on the sides even in July, and it spanned the continental divide. It also had (the non-locals were wont to complain) a distressing lack of guardrails, but that didn’t bother Crawford none. He had a large, comfy barn, a roomy garage next to the mill, and a giant meat freezer. He laid in hay and grain for the alpacas as well as firewood for himself all summer. He made one last big trip to Boulder on the other highway in December and just hunkered down with the alpacas until March. A few trips to the store in the 4x4 would do him then, unless he had to call the vets, but he could handle most of the animal husbandry problems himself.

Crawford was just fine.

But as he watched the young man move computers and electronics equipment into the small one-bedroom cottage in the middle of September, he could not say the same for his new neighbor.

Crawford was out checking the fences, something that was not as difficult with alpacas as it was with other critters. Alpacas didn’t mind being closed up none and didn’t stress a fence or test it in odd places—not like sheep. Crawford had sheep on the other pasture, sure, and a thick wooden fence over there, too, but here, bordering his new neighbor’s scant acre of land, it was not much more than pig fencing, and the alpacas didn’t give a hoot. They just hung out and ate the grass, like they did, and ignored the fence. The other side of the fence might as well have been the other side of the world to their amiable little hearts, and since old Mrs. Humphreys had passed away, it had been to Crawford too.

But this new guy wasn’t old Mrs. Humphreys.

He was young, for one thing. Midtwenties to Crawford’s late-thirties, and bright and shiny as a spit-polished shoe. His hair was cut fashionably long, and he had just enough scruff on his lip and chin to make Crawford think that maybe he kept that scruff full time. He wondered how long it would take for that scruff to grow to beard length, and thought that would be a crying shame, because the boy had a narrow face with a squarish little block of a chin and tip-tilted sea-green eyes. His mouth was wide and smiling, with full lips, and all in all, it would be a real waste to hide that pretty face behind what would probably be sandy-brown hair.

He was also quick to talk, quick to smile, and gregarious. He chatted with the movers and took notes of the good places to eat (there were really only two places where the locals ate, and Crawford listened shamelessly enough to know that the movers knew those places too) as well as where he could find a movie or help if he needed it.

“And if you need help,” one of the young men said (Robbie, Clarence and Angie’s boy, who used to be a hell-raiser in high school but who had settled down now with a wife and two kids), “Crawford here might help you. He’s queer, but don’t let that bother you none, he’s harmless.”

Crawford refused to flush under the boy’s sniping and stared at him until he blushed instead, mumbling something about checking the overhead and disappearing into the truck. The new kid moving in grinned brightly.

“Well since I am, too, that won’t be a problem,” he said with such sunshiney goodwill that Crawford found himself smiling back from his side of the fence.

The two movers took in this information with widened eyes and flushes, and the new kid just rolled his eyes and continued to chat, putting them both back at ease quicker than Crawford had ever been able to. In a few minutes, just that much, they drove off in a choking cloud of diesel exhaust, leaving the kid with his little city car and a thoughtful look on his face as he surveyed his house.

God, Crawford thought uncomfortably. There had been so much those two yahoos had

not

told him.

“You’re going to need more firewood!” he hollered shortly, and the kid looked at him in surprise.

“Really? There’s a gas heater and a whole stack against the side of the house—”

“The gas guy doesn’t always get out regular, and what’s against the house will only do you a week.”

Crawford was twisting lengths of wire over a hole, and he carefully wrapped that last end so it didn’t snag on the alpaca’s valuable fur, and then stood and pulled off his work glove.

“Rance Crawford,” he said shortly, shaking hands with the boy.

That thin face lit up, and Crawford’s work-roughened, lanolin-softened hand was suddenly grasped tightly in bony fingers as the boy pumped his hand with some enthusiasm.

“Hi! My Aunt Gretchen talked about you! I’m Ben, Ben McCutcheon. Gertie sort of left me her place.”

Rance nodded. “I’d wondered how that went. She had a whole passel of relatives out here right after she died. You weren’t one.”

Ben grimaced. “Yeah—she was really my great-aunt, and my mom was sort of the black sheep of the family. It was mostly just her and me, you know? We used to come out here once a year or so when I was little, and I sent her Christmas cards after Mom passed. I didn’t know it, but I was apparently the only member of her family who didn’t think she was batshit crazy or just want her little acre in Colorado.”

Crawford had to smile, because Gertie Humphries had been a tough old bitch who’d once threatened to shoot his best stud because she claimed he scared her best laying hen. Rance had cured her of that in a hot second—he’d knitted up some of Burlingame’s top-notch fleece into a hooded shawl that the old girl had worn even on her deathbed.

Yup, Gertie had liked him in the end, which was why he’d been sorry to see that swarm of kin around her house, likely counting chickens for their celebration dinner. He hadn’t seen what had broken them up and sent them scattering, but now that he’d met the boy, he heartily approved of Ben.

Although that could have been just because he was pretty enough to make Crawford do the pee-pee hard-on dance.

“So,” Crawford said, eyeing the weathered little cottage dubiously, “you’re going to settle in here during the fall?”

Ben grimaced. “It’s a little colder here in the fall than it was in Sacramento,” he admitted.

Crawford stood and straightened, picking up his lightweight denim jacket and putting it on again now that he wasn’t sweating in the thinning sun. “How cold was it in Sacramento when you left?” he asked judgingly, and Ben looked sheepish.

“Ninety-five degrees.”

Crawford knew his eyes had widened. It was laughable. Here in Grand County, near the end of September, at ten o’clock in the morning, it was around fifty degrees. “It may make sixty-five by the afternoon.”

Ben shrugged. “It’s been sort of a shitty long summer.”

Crawford just looked at him. “What’s winter like?”

Again, that shrug. Like living through snows was going to be no big deal. “Mild. Lots of rain—if we’re lucky.”

Crawford nodded and sighed. “You’re going to need a list,” he said on a grunt. “You going to keep the chickens?”

Ben nodded. “Aunt Gertie liked ’em.”

“The rabbits?”

“Why not?”

“She’s got an old sheep named Millicent and a yapping piece of coyote kibble—”

“Yeah, I’m keeping Millie, but my mom’s least favorite uncle took Biddy-Bye for his grandkids to play with.”

Crawford shook his head. Stupid fucker. “The little shit’s gonna eat herself some fingers.”

Ben chuckled and sighed happily. “Yeah. I hope they’re his.”

Crawford turned to him with nothing more than a raised eyebrow, and Ben blushed. “They weren’t nice to my mom,” he mumbled, looking at the small house in the middle of the overgrown grasses. A shrill autumn wind sang through the valley, and the grasses rippled, but even through the ever-present shushing, Crawford heard him when he added, “They weren’t nice to me.”

Crawford nodded then and gathered his tools, rolling them in the leather holster and putting it in the saddlebag. He had a tractor and a motorcycle, but those things made the beasties skittish. A horse was still a good idea with fifty acres to tend.

“I’ll make you a list, then,” he said decisively. “Things you’ll need, shit to prepare for. Winter’s not a joke here. You’d best take it seriously.”

Ben looked at him and smiled, and it was a child’s smile, open and clear and trusting. His green eyes lit up, and he nodded, even as he shoved his hands deeper into his pockets. “I’d like that,” he said happily. “That would be really kind of you. I’ve got money—I just don’t know what to do with it to prepare.”

Crawford looked at him bouncing on his toes in his tennis shoes, shivering a little in his long-sleeved T-shirt. “Money’s a start. When’s it run out?”

“It doesn’t!” Ben smiled again, this time proudly. “I work from home. Independent game companies send me their code, and I clean it up for them. They call me the Bug Man—it’s sort of cool.”

Crawford thought his eyes might bug out of his head. He knew about the Internet, and they got it fine in Granby, but a hotbed of media development they were not. “And you thought you’d relocate here?” He had to ask it. He absolutely had to ask it.

Ben couldn’t look at him anymore. The ever-present wind had blown the clouds over the sun, and the temperature had dropped again. He tilted his head up to the sky anyway; it was vast and open, horizoned by the Rockies on all sides.

“Do you have any idea how high your heart can soar in a place like this?” he asked. His nostrils flared a little, like he was scenting the wind and the animals and even the snow that would probably visit in November.

Crawford’s pee-pee hard-on dance stilled for a moment, and he found himself looking hungrily at that young, pretty face. “You forget,” he said softly, not thinking about the sky at all. He’d gotten lost in the sky years ago—he was well aware he’d never find his way back.

Ben pulled his attention earthward, still shivering, but now looking peaceful and not lost in the sky. “It’s beautiful,” he said simply. “And I was really loved here. I sure would appreciate that list. Should I come over for it?”

Crawford’s brain shorted out. He didn’t want Ben coming over to his place. He was not ashamed of it—the mill, the connected store, the house next to that—he was proud of all of them. It was just that suddenly, these places were…

personal.

They were personal, and he only wanted Ben to see them if

he

was going to be

personal

too.

“I’ll bring it in the morning,” he said. “On my way to town. I’ll take you. There’s firewood for sale. You’re going to need it. I’ve got a truck.”

Maybe, with a little bit of revising, he might have made the whole speech a little more rock-bottom terse, but it was the best he could do on improv.

Ben didn’t seem to care, though. He nodded seriously, like a child taking orders. “What time?”

“Eight thirty.” Because he was up at six, the lumberyard with its supply of firewood opened at nine, and he had to be back at ten thirty to open the shop. He could do it, he was pretty sure. “I’ll have the list,” he added before swinging himself up on top of his patient horse. Everclear had sat docilely, eating grass and giving Sourmash, Edna, and Hankity the evil eye so they’d stay away from him, but as soon as he felt Crawford’s weight, damned if that gelding didn’t give a disgusted little snort and jerk his head toward Miss Gertie’s place instead of away from it. Crawford gave the reins a little jerk back and eyed the horse with suspicion. It didn’t pay to give the horses their head too much—they tended to think worse of you.

“I really appreciate the help,” Ben said, his gratitude as open and as transparent as the sky.

Of course he appreciated the help. He was like to freeze to death without it. Crawford grunted something, probably something socially inept and grim, and swung Everclear away and down toward the mill. God, he had shit to do.

Chapter 2

Scarf

Crawford wasn’t sure exactly how it happened. He finished tending the fences, tended to the animals, and went into the shop. His two journeymen were there, running the mill itself, and Ariadne, his frighteningly appropriately named apprentice, was in the shop, talking to a nice middle-aged woman about qiviut.

“Yeah,” Ariadne was saying. “We’re lucky. We’ve got a co-op agreement with a First Nations reservation up in Canada. They collect the fiber after the musk ox molt. It’s expensive because it’s sort of painstaking, you know? That’s why we usually only spin it lace-weight. A skein big enough for a shawl will cost you about $150 to $200, but we have smaller skeins if you want to ply it with another fiber so it goes a little farther.”