The Wisdom of the Radish (5 page)

Read The Wisdom of the Radish Online

Authors: Lynda Browning

Â

Â

Â

I don't know if I'd ever felt the fear of God before, but that day, I did. Faced with a nothing of a farm, a rapidly diminishing savings account, and no employment leads, I worked

hard

. I tried to think positive thoughts about tomato jungles, bean forests, and squash thickets, but my mind kept slipping back to the empty flats of deceased seedlings. Fortunately, there wasn't too much time to thinkâit took considerable concentration to make my weak shoveling muscles follow orders.

hard

. I tried to think positive thoughts about tomato jungles, bean forests, and squash thickets, but my mind kept slipping back to the empty flats of deceased seedlings. Fortunately, there wasn't too much time to thinkâit took considerable concentration to make my weak shoveling muscles follow orders.

We heaped manure into seven twenty-foot lines and adjusted them for straightness. Then we dug each row out by hand, turning the manure into the cloddy clay. Once each row was dug, we poured a line of soil amendments onto it, then hoed them in. The alfalfa meal, soft phosphate, ground mussel shell, and kelp meal all had to be poured separately, and each triggered a separate allergic reaction. By mid-afternoon, I was sneezing in sets of five and my eyes were watering fiercely.

We punched holes in black drip hose, then pushed red nipples into the holes until my fingertips were numb, indented, and no longer able to complete the task. By the time the rows were finished, and trenches were dug for future sowing, I was exhausted. And yetâdespite my chronically itching nose and drip-irrigation eyesâa feeling of vague satisfaction crept up alongside my general state of scared shitlessness as we boarded the Gator and drove off.

It occurred to me that never before had I held a job this tangible, one where I could glance over my shoulder as I drove away and actually see the results of my labor.

We sat down at the dinner table that night to plan out our field and assess our options, which were diminishing approximately as rapidly as our savings accounts. We spread our beautiful heritage seed packets out on the table and scrutinized the information on the back. As one packet after another cited maturity times of 60, 75, 90, and even 120 days, we realized that we'd have to abandon visions of decadent cornucopias for the time being. By the time any of those crops were ready to sell, the farmers' market season would be half over and we'd be mired deep in farm debt. But baby greensâwith a maturity time of twenty-one to thirty daysâcould, perhaps, pinch hit until the stars of the season deigned to show up.

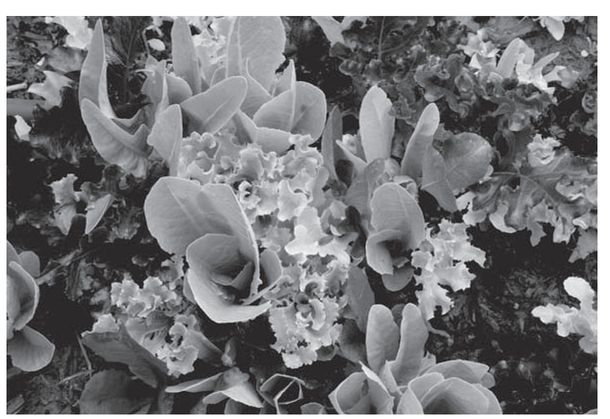

Emmett had already planted one bed of baby greens half in brassicas, half in lettuces. We'd plant another right away, and one more a week later. In other ASAP crops: radishes, arugula, spinach, chard, and kale. After these were safely in the ground, we'd turn our attention to tomatoes, cucumbers, melons, peppers, and the like.

Baby greens were in short supply at the market, so we hoped that our bags, though few, would sell fast. Oh, how we doted on those greens. We mixed extra alfalfa meal into the soil to ensure a plentiful nitrogen supply. We broadcast the seeds by hand, and tamped down the soil by gently massaging it with our palms. We purchased and installed a series of micro-misters to provide the finest, gentlest watering experience around. We misted them thrice daily, and when the temperatures stretched above 100 degrees F, we brought them plastic shade cloth, an exorbitant expenditure at two dollars per foot, and stretched it over PVC hoops above the greens row so that the baby greens wouldn't be singed by the sun. We monitored them daily for any obvious weeds. And when our

second, half-disaster struck, we hovered over the bed for hours trying to squish the insects that were poking thousands of tiny holes in our thousands of tiny plants.

second, half-disaster struck, we hovered over the bed for hours trying to squish the insects that were poking thousands of tiny holes in our thousands of tiny plants.

As the day of our first market drew near, it became clear that we would have to start out as the salad stall. The bug-munched salad stall. Aside from radishes (which the seed packet noted were “a good choice for kids to grow”), our sales inventory consisted entirely of hole-pocked mini lettuces, tiny tatsoi, itsy bitsy mustard leaves, doll-sized kale, and pretty much anything else that was small, green, and decorated with pin pricks. Since we were about to rely entirely on baby greens for our initial farmers' market sales, it was time to bone up on my lettuce smarts.

Rumor has it that the English word “lettuce” comes from an Old French word,

laities

, meaning milkyâprobably referring to the milky white sap that comes out of mature lettuce stems after the farmer snips off the leaves. Like milk, these leafy greens have a long tradition of popularity. Lettuce dates back at least as far as the sixth century before Christ when Persian kings dined on fresh-cut leaves at their banquet tables. By the first century after Christ, at least twelve different varieties were known to the Romans. Note that none of these were head lettuces, but rather loose-leaf varieties; head lettuces didn't come onto the scene until centuries later.

6

By the early years of America's independence, Thomas Jefferson was growing fifteen varieties of lettuce in his gardens at Monticello.

7

laities

, meaning milkyâprobably referring to the milky white sap that comes out of mature lettuce stems after the farmer snips off the leaves. Like milk, these leafy greens have a long tradition of popularity. Lettuce dates back at least as far as the sixth century before Christ when Persian kings dined on fresh-cut leaves at their banquet tables. By the first century after Christ, at least twelve different varieties were known to the Romans. Note that none of these were head lettuces, but rather loose-leaf varieties; head lettuces didn't come onto the scene until centuries later.

6

By the early years of America's independence, Thomas Jefferson was growing fifteen varieties of lettuce in his gardens at Monticello.

7

Fast forward to the twenty-first-century United States. Today, lettuce is a common household item and has the highest production value of any U.S. crop. California and Arizona account for approximately 98 percent of all domestic lettuce productionâand, surprisingly, nearly all head lettuce sold in the United States is actually grown in the United States.

8

That's

in large part because lettuce can be grown year-round here. If you go to the grocery store and pick up a bag of precut, prewashed lettuce any time from April through October, it probably came from the Salinas Valley in California, just east of Monterey. If you buy that same bag any time from November through March, it came from Yuma, Arizona, or the Imperial Valley. (Huron, California, typically fills in the seasonal transition periods.) This, truly, is food as businessâa smoothly operating machine offering consistent supply and quality.

8

That's

in large part because lettuce can be grown year-round here. If you go to the grocery store and pick up a bag of precut, prewashed lettuce any time from April through October, it probably came from the Salinas Valley in California, just east of Monterey. If you buy that same bag any time from November through March, it came from Yuma, Arizona, or the Imperial Valley. (Huron, California, typically fills in the seasonal transition periods.) This, truly, is food as businessâa smoothly operating machine offering consistent supply and quality.

Our first cash crop: baby greens.

And then there was The Patch, which offered neither consistent supply nor quality.

The big baby lettuce operations, like Earthbound Farms, plant each variety of lettuce separately and then combine the different types after harvest to create that lovely mix of green and red tints. We planted a seed mix so that all the lettuces grew together in a dense, biodiverse rainbow bed. Often, the faster growing varieties outpaced the slower ones, leaving us

with giant green leaves and teensy red ones. The big farms specialize in multi-acre swaths of one crop, providing a single type of food for thousands of Americans. We grew a row of lettuce immediately surrounded by chard, beets, carrots, and potatoes to provide an entire meal for a few local families. They plant with ever-evolving machines; we used a more timetested method: a rake and our hands. The big farms employ laser-leveled planting beds so that their harvesting machines can cruise over and scoop up baby leaves with precision.

9

We weren't so technical; that first market morning we snipped the leaves with scissors, our hands automatically adjusting to the depressions and hills of our uneven planting bed. The big players store their lettuce just above freezing, at 98 percent humidity, with a two- to three-week shelf life.

10

They typically inflate their lettuce bags with noble gases to prevent oxidation and enhance freshness. We plopped our lettuce in a cooler surrounded by run-of-the-mill troposphere until it made its way onto the market table and into a basket, whereâif hand-misted with a spray bottleâit might stay fresh for a couple of hours. The California lettuce industry harvests more than 40,000 acres of loose leaf lettuce in a single year.

11

So far, we had planted about forty square feet. The industry earns about 300 million dollars annually,

12

but at that first market, we made, oh, fifty dollars on lettuce sales. Depending upon whether you're a pragmatist or a romantic, you might describe our tenderfoot farm as either dinky or spunky. Either way, it's safe to say we were a well-intentioned-but-muddy drop in the far larger bucket of efficient, effective commercial agriculture.

with giant green leaves and teensy red ones. The big farms specialize in multi-acre swaths of one crop, providing a single type of food for thousands of Americans. We grew a row of lettuce immediately surrounded by chard, beets, carrots, and potatoes to provide an entire meal for a few local families. They plant with ever-evolving machines; we used a more timetested method: a rake and our hands. The big farms employ laser-leveled planting beds so that their harvesting machines can cruise over and scoop up baby leaves with precision.

9

We weren't so technical; that first market morning we snipped the leaves with scissors, our hands automatically adjusting to the depressions and hills of our uneven planting bed. The big players store their lettuce just above freezing, at 98 percent humidity, with a two- to three-week shelf life.

10

They typically inflate their lettuce bags with noble gases to prevent oxidation and enhance freshness. We plopped our lettuce in a cooler surrounded by run-of-the-mill troposphere until it made its way onto the market table and into a basket, whereâif hand-misted with a spray bottleâit might stay fresh for a couple of hours. The California lettuce industry harvests more than 40,000 acres of loose leaf lettuce in a single year.

11

So far, we had planted about forty square feet. The industry earns about 300 million dollars annually,

12

but at that first market, we made, oh, fifty dollars on lettuce sales. Depending upon whether you're a pragmatist or a romantic, you might describe our tenderfoot farm as either dinky or spunky. Either way, it's safe to say we were a well-intentioned-but-muddy drop in the far larger bucket of efficient, effective commercial agriculture.

So there I stood at the farmers' market, neither salesman nor farmer, but something closer to a half-deflated idealist. One with nerdy, grandiose signs lording over her piddling produce.

What seemed like a good idea the night beforeâwhen we were wracking our brains for something, anything, to sellâlooked ridiculous next to Farmer Cindy and The Grocery Store. In permanent-marker bubble letters, we'd labeled the common rosemary pilfered from Emmett's parents' garden as “Fresh Seasoning, Rosemary: For baking with potatoes, chicken, and salmon.” Never mind that the stuff grows along half the sidewalks in Northern California and we wouldn't sell a single stem.

And yet somehow, over the course of three hours, customers started buying things. One at a time, haltingly at firstâand then, miraculously, we actually had a small

line

forming in front of our paltry stand. Maybe they came out of pity, maybe out of curiosity, but hey, a buck's a buck. And besides, we were the only ones at the market with bagged salad. It couldn't all be pity.

line

forming in front of our paltry stand. Maybe they came out of pity, maybe out of curiosity, but hey, a buck's a buck. And besides, we were the only ones at the market with bagged salad. It couldn't all be pity.

At the end of the day, we counted our earnings: ninetyeight dollars, minus 10 percent for our stall fee.

“How'd you kids do?” Grumpy asked as I carried my envelope to the market manager.

“Not bad,” I said.

“That's actually pretty good,” my fifteen-year-old brother, Bobby, said. (We dragged him to the market with us; in town on a visit from San Diego, he was more likely to be found behind a computer than a card table full of organic greens.) “If you divide it by three, that's thirty bucks an hour.”

This cheered me considerablyâmy salary was downright respectable!âuntil Emmett, ever the practical one, pointed out that it wasn't just the hours I'd spent selling; it was the hours I'd spent sowing, watering, weeding, and transplanting. And the hours

he'd s

pent sowing, watering, weeding, and transplanting.

he'd s

pent sowing, watering, weeding, and transplanting.

We'd touched each lettuce leaf at least five times before placing it on the table. Once when it was a seed, hand-scattered into a bed, massaged with the back side of a rake, and palmpressed into the soil. At least three times when I'd pulled out the weeds threatening to choke it: tendrils of bindweed, wild mustard sprouts, and prickly scotch thistle seedlings. Then again when it was hand harvested, snipped leaf by leaf, and placed in a harvest bin.

And when you add those hours in, my wage was substantially less impressive: $0.13 an hour if you omit the investment; â$1.95 per hour (yes, that's negative) if you consider the money we'd put in up front.

As we broke down the card table and packed up the station wagon, Emmett shared a joke.

A farmer wins the lottery. A reporter asks him, “What will you do now that you have all that money?” The old, weatherbeaten man stares into the distance, turns back to the reporter, and without a hint of irony says, “I suppose I'll keep farming until it's all gone.”

Chapter 2:

BUNCHES

Chard, Kale, and Bok Choy

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

I stood at the farm stand, jaw set, and imagined my marketing pitch.

It wouldn't be in my voice, of course: the words would boom out approximately one octave lower in that brassy, gravelly made-for-radio tone that has always reminded me of a trombone.

It wouldn't be in my voice, of course: the words would boom out approximately one octave lower in that brassy, gravelly made-for-radio tone that has always reminded me of a trombone.

Move over, Whole Foods.

The Foggy River Farm market stand is back and bigger than ever. Not to mention we're fresher, cheaper, and way more local than youâbut while we're bigger than before, we're still intimate and friendly. If customers want to know how and where their food was grown and harvested, all they have to do is ask us, the farmers who grew it. How was it grown? Completely naturally, using only the finest locally sourced soil amendments and no pesticides. Where was it grown? An eight-minute drive from here. When was it picked? This morning, about two hours before the market opened.

Side note to brand managerâyou can see by our folksy, handscrawled, permanent-marker poster and hand-painted wooden sign that our marketing strategy is ten times more authentic than

yours could ever be. Your carefully cultivated artificial ambiance is our way of life. Our new tableâan old door, rescued from the town dump and perched on collapsible sawhorsesâsays: we're here, we're real, we're farmers. Above it hangs our beautifully redundant Certified Producer's Certificate (a certificate certifying that we're farmers), and alongside that, our newly certified hanging scale, purchased for $199.35 and sealed for accuracy by the Agriculture Commissioner for $61. And did I mention that we're selling at two farmers' markets now? Healdsburg on Saturday, Windsor on Sunday. Each market's an eight-minute commute from our fields, one south and one north. How quaint and local is

that

?

yours could ever be. Your carefully cultivated artificial ambiance is our way of life. Our new tableâan old door, rescued from the town dump and perched on collapsible sawhorsesâsays: we're here, we're real, we're farmers. Above it hangs our beautifully redundant Certified Producer's Certificate (a certificate certifying that we're farmers), and alongside that, our newly certified hanging scale, purchased for $199.35 and sealed for accuracy by the Agriculture Commissioner for $61. And did I mention that we're selling at two farmers' markets now? Healdsburg on Saturday, Windsor on Sunday. Each market's an eight-minute commute from our fields, one south and one north. How quaint and local is

that

?

Really, given the chance, who

wouldn't

want to shop at our little down-home stand? But let me offer one small confession: while you display only platonic ideal produce, casting aside all those leaves, roots, and fruits that harbor the slightest earthly imperfection, our produce is, um, definitely earthly. As in been through Purgatoryâand maybe through a few levels of hell and backâbefore settling, with great, wounded weariness, on our wobbly table.

wouldn't

want to shop at our little down-home stand? But let me offer one small confession: while you display only platonic ideal produce, casting aside all those leaves, roots, and fruits that harbor the slightest earthly imperfection, our produce is, um, definitely earthly. As in been through Purgatoryâand maybe through a few levels of hell and backâbefore settling, with great, wounded weariness, on our wobbly table.

Other books

The Tale of Cuckoo Brow Wood by Albert, Susan Wittig

Fire Spell by T.A. Foster

Bound to Please by Lilli Feisty

The Way of Muri by Ilya Boyashov

Home Again by Ketchum, Jennifer

Strip Tease by Carl Hiaasen

Fusion by Rose, Imogen

Two to Wrangle by Victoria Vane

Wild Decembers by Edna O'Brien

The New Girl (Downside) by S.L. Grey