The Wisdom of the Radish (6 page)

Read The Wisdom of the Radish Online

Authors: Lynda Browning

Well, back to reality. I couldn't blame the bok choy for looking so exhausted. Our farm was under siege. Just when we'd started to chortle over our chardâhaving outsmarted the summer sun by abandoning the hoophouse and adopting a direct-seeding strategyâmysterious things began to appear on our plants' waxy green leaves.

And by mysterious things, I mean holes. Millions of dastardly, ugly, big and small holes. Emmett had been crouched down above fourteen-day-old greens, weeding, when he made the discovery.

“Hmmmm,” he said, and there was a certain lilt to his voice that made me pause from my beet weeding.

“What's wrong?”

“Something's eating the baby brassicas.”

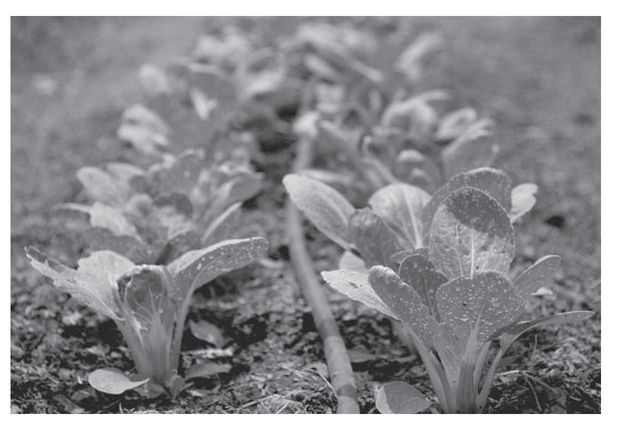

Our battle-worn bok choy was tasty but not quite worthy of a Whole Foods display.

I squatted down beside him. When I brushed my hand over the soft greens, a half dozen little black things scattered. Isolating one, I realized that it was an impossibly tiny beetle, its shell black and oily, shifting and tossing off multicolored light.

I pinched a small mustard leaf between my fingers, still green, not yet showing its mature purple. It was pierced through with dozens of tiny holes.

Two words popped into my mind:

crop failure

. It was a phrase I'd seen in seed catalogs. As in, “No Russian Banana seed potatoes for 2008. Crop failure.” At the time, I had thought, “What kind of an idiot has a crop failure? Don't these people grow things for a living? Short of a hurricane, fire, flood, or a few tons of salt being accidentally dropped in your field, crop failures are inexcusable. If you can't avoid failure, get a different job, for God's sake.”

crop failure

. It was a phrase I'd seen in seed catalogs. As in, “No Russian Banana seed potatoes for 2008. Crop failure.” At the time, I had thought, “What kind of an idiot has a crop failure? Don't these people grow things for a living? Short of a hurricane, fire, flood, or a few tons of salt being accidentally dropped in your field, crop failures are inexcusable. If you can't avoid failure, get a different job, for God's sake.”

In retrospect, perhaps that reaction was a bit harsh. After all, we were now facing our

second

crop failure. (And that's being generousâif you count all the crops separately, we were in the mid-twenties.) Having already killed one farm's worth of summer seedlings, as a follow-up act we had unwittingly invited a Biblical plague to destroy our interim cash crops.

second

crop failure. (And that's being generousâif you count all the crops separately, we were in the mid-twenties.) Having already killed one farm's worth of summer seedlings, as a follow-up act we had unwittingly invited a Biblical plague to destroy our interim cash crops.

The destruction wasn't, unfortunately, limited to the baby brassica mix. The bok choy appeared peppered by machine gun fire, each baby leaf scarred with dozens of tiny punctures. Ditto the arugula. In fact, all members of the brassica family that were located in the farm's main field had become heavy artillery targets.

And then there was the Bright Lights Swiss chard, whose Technicolor stems were just lengthening and broadening to support hand-sized dark green leaves. The poor chard suffered a different sort of wound. The leaves seemed to have had the life and water sucked out of them, tattered fringes left browned and shriveled on an otherwise healthy plant. But this burn seemed bug based; it appeared on all parts of the leaf's surface whether or not the leaf was directly exposed to sunlight.

Fanning out over the battlefield, I noted that our green and purple bean seedlingsâonly recently emerged from the groundâlooked as if they too had been transplanted from some Middle Eastern garden swept up in a sudden desert storm. They were battered, torn, and full of holes.

Our beautiful produce was defaced, defiled, destroyed. Emmett mourned, I swore, and we both headed to the computer to identify our adversaries and plan our counterattack.

This wasn't guerrilla warfare: our adversaries were easily identifiable. When we stumbled across their name it was a eureka moment, albeit one accompanied by yet another sinking feeling in my stomach.

The tiny, iridescent specs that bounced off of our bok choy every time I flicked a leaf were known as flea beetles. It fit, in a painfully obvious sort of way: they look like fleas, but they're beetles. And like their namesake, flea beetles are miniscule critters that can hop many times higher than their body size. Instead of suckers, though, these critters are chewers. Tiny, repetitive chewers who poked scads of tiny holes in our formerly beautiful greens.

But could undersized scarabs be solely responsible for a crop failure? A quick bit of research revealed that our adversaries dine almost exclusively on the Cruciferae familyâalso known as the brassicas. It's no surprise, then, that our baby brassica mix had been attacked. Bok choy, arugula, and kale are also members of the targeted family, which explains why they, too, looked like Havarti cheese.

But tiny flea beetles poke tiny holes. There had to be a second army advancing on our crops, one with bigger weapons.

Our hunt led us to the cucumber beetle. Known to the educated as

Diabrotica undecimpunctata

, and to us as any of several four-letter words, cucumber beetles have only one saving grace: they look like green ladybugs. This might seem insignificant until you're at a farmers' market and one crawls out of a lettuce bag in front of a customer. At that point, 99 percent of customers will say something like, “Look! A ladybug! How cute, I've never seen a green one,” and your butt is covered. If a cucumber beetle resembled an earwig, a cockroach, a swollen tick, or a horsefly, our sales would likely have diminished by half.

Diabrotica undecimpunctata

, and to us as any of several four-letter words, cucumber beetles have only one saving grace: they look like green ladybugs. This might seem insignificant until you're at a farmers' market and one crawls out of a lettuce bag in front of a customer. At that point, 99 percent of customers will say something like, “Look! A ladybug! How cute, I've never seen a green one,” and your butt is covered. If a cucumber beetle resembled an earwig, a cockroach, a swollen tick, or a horsefly, our sales would likely have diminished by half.

It's sheer luck that the diabolical

Diabrotica

bears resemblance to the red polka-dotted celebrity of the insect world. But good looks aside, the cucumber beetle army was a force to be reckoned with. As though it isn't bad enough to defile

pristine leaves and eat giant holes through everything, cucumber beetles also transmit mosaic virus and bacterial wilt while they move from plant to plant. An insidious adversary, the bug renders the plant ugly, and then deposits diseases that may cause it to wilt and die. In the cold of winter, when the bugs go dormant, the viruses stay safely protected in their intestines until spring blossoms and the bugs thaw out enough to resume their reign of terror.

Diabrotica

bears resemblance to the red polka-dotted celebrity of the insect world. But good looks aside, the cucumber beetle army was a force to be reckoned with. As though it isn't bad enough to defile

pristine leaves and eat giant holes through everything, cucumber beetles also transmit mosaic virus and bacterial wilt while they move from plant to plant. An insidious adversary, the bug renders the plant ugly, and then deposits diseases that may cause it to wilt and die. In the cold of winter, when the bugs go dormant, the viruses stay safely protected in their intestines until spring blossoms and the bugs thaw out enough to resume their reign of terror.

In lieu of regular pesticide use, we turned to hand-tohand combat: mechanical management, or physical removal of the bugs from the plants. Some folks actually vacuum up cucumber beetles, dust-busting them to their doom. But because we lacked an electrical outlet, we tried the “catch and crush” technique.

This was far less fun than the alliteration would suggest. For a girl who once threw (and still occasionally throws) conniptions over earthworms, I didn't easily embrace squeezing green bug guts out of a beetle's butt. By the third or fourth bug, my fingertips were stained green and the thought of ever eating again had begun to lose its appeal. As I watched at least two cucumber beetles fly to safety for every one I was able to catch, I got the distinct impression that I was fighting a losing battle.

Besides, we were only catching the adult beetles. Chances were, the ones we were squishing that day had already mated and produced hundreds of little eggs just waiting to hatch out more evil. There was no shortage of reinforcements to replace the fallen: each spotted female lays two hundred to three hundred eggs over the course of a couple weeks. The eggs can hatch in just five days and pass through the larval stage quickly, becoming horny young adolescents in as few as eleven days. After they've reached adulthood, they enjoy a leisurely two months during which they can parade around my

vegetable rows, eating my chard and hiding their godforsaken eggs under every bean leaf.

vegetable rows, eating my chard and hiding their godforsaken eggs under every bean leaf.

More bad news: These guys don't just eat chard and beans. They also have an appetite for a long list of other crops, including potatoes, squash, corn, cucumbers (no surprise there), melons, and over 260 other plants in 29 families.

And, of course, whatever vegetables the

Diabrotica

didn't eat were swarming with flea beetles.

Diabrotica

didn't eat were swarming with flea beetles.

Once we knew who we were dealing with, the question was how to deal with them. After our futile attempt to catch and crush all five million cucumber beetles, our next strategy was one of mitigation. (Well, Emmett called it mitigation; personally, I considered it denial.)

We ignored the disaster, continued to sow more seeds, and hoped that the pests didn't completely kill the plants before we had a chance to sell them. Then we did our best to wash all evidence of insects off of the produce during our predawn harvest on the day of market. We dumped the produce into a harvest bin, filled it with water, and rustled the produce violently to try and dislodge the creepy crawlies. Then we drained the bin and repeated the process all over again. It was awkward to try and siphon off the free-floating flea beetles before they could land on hopeful islands of baby greens, but after a couple of rinses, any extra protein was minimal enough to be unnoticeable to the untrained eye.

But these were only stopgap measures. Selling damaged produce wasn't a solid business plan; the majority of our sales were pity purchases accompanied by a sympathetic sweet nothing. “Bad year for bugs, huh?” True, a certain species of diehard locavore approves of holes in produce as evidence of nongovernmental organic certification, but those customers were few and far between in half meat-and-potatoes, half gourmet

Sonoma County. Meat-and-potatoes Sonoma County could get hole-free greens at Walmart for less money. Gourmet Sonoma County wanted palate

and

picture perfection.

Sonoma County. Meat-and-potatoes Sonoma County could get hole-free greens at Walmart for less money. Gourmet Sonoma County wanted palate

and

picture perfection.

And the sting wasn't just that damaged produce didn't sell well. It was also that Emmett and I had spent countless hours coddling these plants. We had improved the soil with loads of organic soil amendments and manure, carefully sowed the seeds by hand, and hunched over the sprouts plucking weed invaders until our backs ached. We were growing these greens to be beautiful, shining examples of sustainable agricultural production. We were not growing them to be prematurely destroyed by ungrateful, sapsucking, motherfucking bastards.

Environmental ethos be damned. This meant war. So much for live and let live; hello, shock and awe.

If I had been (just hypothetically speaking here) a conventional farmer, I would have bombed the living daylights out of those bugs. One of the most common beetle killers on the market is named “Adios,” clearly carrying a certain Arnold Schwarzenegger machismo. Its generic name is carbaryl, and it's a known mutagen and suspected human carcinogen. Although it's legal in the United Statesâand is one of the most popular broad-spectrum insecticides in agriculture, turf management, ornamental production, and residential marketsâit's banned in the UK, Germany, Sweden, Austria, Denmark, and several other countries. Under the Bush administration, the EPA found in a review of carbaryl's status that “although all uses may not meet the current safety standard and some uses may pose unreasonable risks to human health and the environment, these effects can be mitigated ...”

13

In other words, “It's really dangerous, but eventually we'll figure out a way to make it less so. And in the meantime, feel free to use it.”

13

In other words, “It's really dangerous, but eventually we'll figure out a way to make it less so. And in the meantime, feel free to use it.”

Carbaryl, a neurotoxin, is also directly responsible for the death of fifteen to twenty thousand

14

people in Bhopal, India. To put that estimate in perspective, the upper range is equivalent to

twice

the number of American deaths caused by Hurricane Katrina, the collapse of the World Trade Centers, the war in Iraq, and the war in Afghanistan combined. The notorious Union Carbide plant that accidentally emitted fortytwo tons of toxic gas in the middle of a densely populated city did so in the process of manufacturing this pesticide.

14

people in Bhopal, India. To put that estimate in perspective, the upper range is equivalent to

twice

the number of American deaths caused by Hurricane Katrina, the collapse of the World Trade Centers, the war in Iraq, and the war in Afghanistan combined. The notorious Union Carbide plant that accidentally emitted fortytwo tons of toxic gas in the middle of a densely populated city did so in the process of manufacturing this pesticide.

But if I found carbaryl too creepy, I could always go the nerve gas route. Malathion, another common pesticide, is a member of the organophosphate family that operates by disrupting neurotransmissionâleading to convulsions, respiratory paralysis, and death. Its chemical cousins were developed to be dropped on unsuspecting enemy soldiers in World War II. Today we apply it to agricultural pests, and regularly consume food that's been bombed by nerve gas.

Frankly, I didn't want to eat food that had been poisoned, much less apply those poisons myself. The health risks agricultural workers face are considerably greater than those facing consumers. In one study, 96 percent of surveyed farm workers reported direct exposure to pesticides.

15

Over half of respondents noted that pesticides touched their skin, over half breathed in pesticide dust, and 17.3 percent had actually been directly dusted or sprayed. Sadly, the exposure doesn't end at the field. Back home, the families of agricultural workers breathe in house dust that contains seven times the concentration of organophosphates as compared to nonagricultural families.

16

Eighty-eight percent of farm workers' children test positive for organophosphate metabolites in their urine.

17

Those are health risks I'd rather do without.

15

Over half of respondents noted that pesticides touched their skin, over half breathed in pesticide dust, and 17.3 percent had actually been directly dusted or sprayed. Sadly, the exposure doesn't end at the field. Back home, the families of agricultural workers breathe in house dust that contains seven times the concentration of organophosphates as compared to nonagricultural families.

16

Eighty-eight percent of farm workers' children test positive for organophosphate metabolites in their urine.

17

Those are health risks I'd rather do without.

But if the conventional pesticide news is dire, the good news is that there are plenty of pesticides certified by the Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) and approved by the USDA for use on organic farms. If we chose to go the organic route, our arsenal could have included all kinds of toxic (but present in nature, and therefore supposedly safe) substances. The more I learned about pesticides, even organic ones, the more I realized that the creativity of chemists when it comes to taking life is downright disturbing.

Other books

The Perfect Mother by Nina Darnton

Dead Iron by Devon Monk

Hillary Clinton: Renaissance Woman by Karen Bartet

The Death Collector by Neil White

Bad Boy by Jordan Silver

Creations 4: Caging the Beast by Marie Harte

Amber Eyes by Mariana Reuter

Beneath the Surface by M.A. Stacie