The Zombie Combat Manual (33 page)

Read The Zombie Combat Manual Online

Authors: Roger Ma

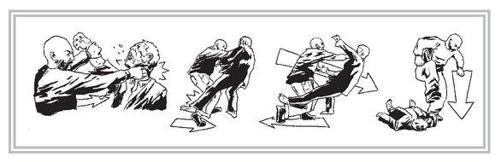

3. Sweep your leg back while pushing against its neck, forcing the zombie to the ground.

4. Quickly move toward the zombie’s head and stomp on its skull with your heel.

Here again is an illustration showing the sequence in its entirety:

Those of you with previous martial arts experience may recognize both of these maneuvers as variations of two classic techniques—the

osoto-gari

(major outer reap) and the

ouchi-gari

(major inner reap). Martial artists may be tempted to try other techniques learned in various self-defense classes against an undead adversary. Unless you are willing to sacrifice your life to the benefit of your art, testing other random techniques is not encouraged. This is not to say that other movements would not work on a walking corpse, but are you prepared to take that chance?

These two variations on traditional techniques work well because (1) they are executed easily, (2) you are in constant control of the attacker’s mouth, and (3) grappling with the zombie is kept at a minimum. If you are tempted to try other maneuvers such as shoulder throws, hip tosses, or back throws, you are likely to feel a set of undead teeth sinking into your shoulder, forearm, or neck. The biting and clawing attacks used by a zombie are banned in every professional human combat sport setting. They are also tactics that many martial artists are not used to defending against regularly, unless they have extensive experience in the most vicious of street brawls.

No disrespect is intended to any individual style or category of martial arts, but many classical methods do not translate well against the undead. Techniques that rely on pain to generate a calculated response from your adversary are particularly ineffective. Recall our discussion on melee combat regarding the futility of hacking a ghoul to pieces. Unlike a human being, a zombie will never surrender or “tap out,” and it will let you snap every bone and hyperextend every joint in its body, all the while attempting to bite you as you do so. Traditional kicks and punches are not only ineffective against undead adversaries, they may actually do more harm than good should you lacerate the skin of your fists against the infected flesh of your opponent. For advanced training, you should study one of the specific zombie combat arts to gain knowledge in techniques that have been tested to work specifically against the walking dead.

COMBAT REPORT: ERIC SIMONSON

Grandmaster, Shigai-Jitsu Red Rock, Arizona

I drive up to what looks to be a nondescript warehouse. From the outside, the structure could pass for a storage facility, retail wholesaler, or lumber supply depot. The only evidence of its true purpose is the snaking coils of concertina wire that encircle the complex and a black wooden placard etched in white lettering that reads “Shigai-Jitsu: All Are Welcome.” Eric Simonson stands beneath this sign awaiting my arrival. He is dressed in a traditional black martial arts uniform known as a

gi

. With a warm smile and surprisingly soft handshake, he leads me into his training center. I address him by his official title as “Grandmaster,” which he immediately waves off, feigning embarrassment. “Grandmasters are old men with long, white beards, usually dead. Call me Eric.”

His humility is surprising, even for someone who was previously told of Simonson’s lack of ego. His modesty belies his status as the head of one of seven internationally recognized and federally funded styles of undead self-defense. He is a wiry man with a triathlete’s build and looks decades younger than his actual fifty-four years, the only hint of his age being the streaks of white in his long hair, which is pulled back in a ponytail.

Classes are in session as we walk through the training center. Nearly all the students look identical and drastically different from Simonson—shaven heads, cargo pants, boots, and athletic compression tops. The instructors are dressed the same, with the exception that most wear their hair slightly longer than the students. We arrive at Simonson’s office in the back of the complex, which adjoins a large, open training space. Unlike the areas we passed, this training room contains no equipment or padded surfaces. Dark blemishes stain the concrete floor.

ES:

I still remember where I was during those initial reports. Guess it’s like that “Where were you when Pearl Harbor, JFK, 9/11 . . .” kind of thing. I actually wasn’t in town at the time of the first EMS broadcasts.

ZCM: Where were you?

ES:

Los Angeles, at this semiannual West Coast martial arts leadership conference. They liked to refer to it as a “Gathering of Warriors.”

Pfffft

. Most of the guys I knew were going for three reasons: to get new business, get hammered, and get tail. It was always a good time, and it gave me an opportunity to catch up on some of the newer training methods. Once televised mixed martial arts became the highest-rated sporting event on broadcast television, man, we just couldn’t keep up with the demand. At the same time, we had to differentiate ourselves and stay up-to-date with the latest training techniques coming out of Asia. I was in the exhibit hall looking at some guy connected to what looked like thirty-five rubber bands when a Muay Thai boxer I knew called me into the lobby.

They had the news up on the flat screens. I swear, half of us thought it was some sort of guerrilla marketing campaign or performance art piece—like those collective dance groups or that guy who takes pictures of people bare-ass naked in public. I remember they just kept rolling the same footage coming out of Miami over and over again: this huge mass of them, like some giant, rolling wave of gray and brown. I’d heard some news reports here and there, but nothing like this. I still didn’t believe it until they started showing the footage coming in from around the world—Mumbai, Tehran, Hong Kong. When I saw the stuff from Hong Kong, Jesus. The short hairs on my neck were still standing up as I was speed-dialing my airline to get an earlier flight.

ZCM: You wanted to leave?

ES: Damn straight. I remembered what happened when the shit hit the fan in New York in 2001 and then later in Chicago. At the time I didn’t know whether this was some Al-Aqsa attack or superpandemic or what. I just figured that Red Rock sounded a hell of a lot safer than L.A. Didn’t matter, flights were already being delayed or canceled, and I was stuck with all the other guys at the conference.

ZCM: What was the reaction of the others?

ES:

That was what was most interesting. The reactions I saw in those initial hours exemplified the attitudes I continued to see throughout the initial outbreaks, when we were all too stupid or arrogant to be scared. There was a bunch that were, like any normal human beings, basically freaking out. Some, like me, incorrectly believed that the government would handle the mess before it got too out of control. A majority of them, though, a lot of my friends included, saw this as a unique opportunity to prove themselves.

ZCM: Prove themselves?

ES:

As combat practitioners. After forty years of doing this stuff, this much I know: I don’t care what style, what origin, what country—if you spend a good percentage of your life hitting pads, kicking bags, and rolling around on mats, at the end of the day you want to know that what you’re doing actually works when it counts. Much of what we all practice is theoretical, especially the weapon-based arts. Sure, you can say “I’ll block this strike and then snap the arm at the elbow,” but very few in the civilized world, instructors included, know the specific level of force required to crack a radial bone. Even fewer have actually done it. This is even truer in the blade arts, given that most legal systems frown on people slicing each other to ribbons.

I’m not sure how much you know about how mixed martial arts got ramped up in the States. For decades, it was that age-old “My kung fu is better than your kung fu” boasting. Then fighters of all styles started getting into cages in the early nineties. That’s when the entire martial arts world got flipped on its ear. It caused a sea change throughout the fighting styles. Everyone realized that unwavering commitment to any one style, regardless of what it was, wouldn’t work in a real fight. Bruce Lee, smart SOB that he was, said it best way back in the seventies: Be like water. Be flexible—keep what works, toss what doesn’t, keep learning. Everyone had to get out of their comfort zone and train in a different set of techniques: wrestling, jujitsu, boxing, judo. And you know what? In the end, we were all better for it. Better martial artists, and better people. More humble, more open, more willing to learn.

After years of being flexible, we started to get cocky again. A lot of us thought we had it all figured out, and now some of us wanted to prove it. Against them.

We had come full circle, and were back to seeing whose kung fu was best. I remember this one guy at the convention, a huge, tattooed judoka, turned to me, wrung his hands in delight like a kid in a cupcake shop, and yelled “Rock and roll!” A bunch of the other guys laughed. They saw this as open season—a prime opportunity to use techniques that would normally get them tossed from competition or thrown in jail. You would have thought that these guys would know better; they were supposed to represent the vanguard, the leadership from their respective styles. I wish I could say that these feelings were isolated. I don’t know what it was—validation, insecurity—but in those first months, I saw a lot of good men, good fighters, throw their lives away. For what?

ZCM: You didn’t have the same urge?

ES:

Never. Maybe it was because I was older, had a family. Maybe I worked out all that testosterone-fueled horse crap in my twenties. It also just didn’t make sense to me, especially early on, when no one had a clue what the hell we were up against. It was just blind ignorance. No fighter in his right mind would get into a ring before studying his opponent, right? At that point, we knew less than nothing about what was going on around us. All we saw were these slow, lumbering mental defects. “Eric, it’ll be like kicking fish out of a barrel,” I remember one guy saying. We had no knowledge, and no respect for the opposition. We underestimated them. And in a fight, that’s precisely when you lose.

The boxers took it on the chin the worst, no pun intended. Everyone had to swallow at least a small chunk of humble pie when all was said and done, but the boxers, they were the first to suffer. A boxer’s weapons are his fists, and what good are they against an opponent that does not,

cannot

get knocked out? There was this one friend of mine, Manuel, awesome fighter out of Albuquerque. Golden Gloves three years in a row, most of his Ws by knockout. I had him out to the dojo a few times to run some clinics for the group.

He points to a picture on the wall of a stout, handsome Latino, his hands raised in a boxer’s stance, standing alongside Simonson and other students.