Theory of Fun for Game Design (11 page)

Read Theory of Fun for Game Design Online

Authors: Raph Koster

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Programming / Games

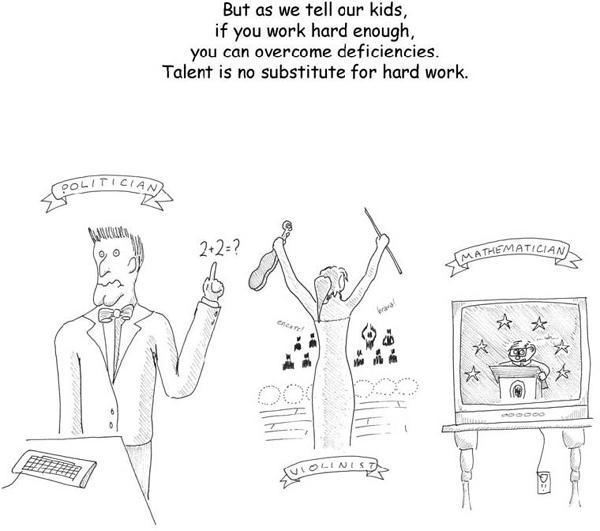

In recent years, much study has been centered on gender differences. It has finally become acceptable to discuss this topic without accusations of sexism. It’s important to realize that in all cases, we’re speaking in generalities, of averages. On average, females tend to have greater trouble with certain types of spatial perception—for example, visualizing the cross section of an arbitrary shape that has been rotated to a different facing. Conversely, males tend to have greater trouble with language skills—doctors have long known that it takes longer for boys to become verbally proficient.

It speaks well of the power of video games that they can actually change this. After all, the equation is both nature

and

nurture. Research has shown that if women who have trouble with spatial rotation tests are given a video game that encourages them to practice rotating objects and matching particular configurations in 3-D, not only will they master the spatial perception necessary, but the results will be

permanent

.

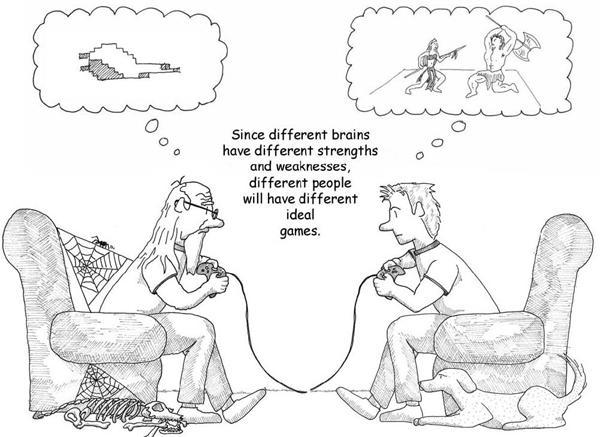

One researcher in the U.K., Simon Baron-Cohen, has concluded that there are “systematizing brains” and “empathizing brains.” He identifies extreme systematizing brains as being autistic and ones just slightly less so as being those diagnosed as having Asperger’s syndrome. The distribution curve of systematizing brains versus empathizing brains, according to Baron-Cohen, is apparently influenced by gender. Men are more likely to have systematizing brains, and women more likely to have empathizing brains.

According to Baron-Cohen’s theory, there are people who have high abilities in both systematizing and empathizing. One would surmise that these people tend to go into the arts, which are heavily systematic and also require a high degree of empathy. Baron-Cohen postulates that having high abilities in both is a contraindicated survival trait since it means that they are almost certainly not as good at either as the “specialists.” This may explain all those consumptive poets dying in garrets.

Another way to look at this is not in terms of intelligence but in terms of learning styles. Here again, gender shows itself. Men not only navigate space differently, but they tend to learn by trying, whereas women prefer to learn through modeling another’s behavior.

The classic ways of looking at learning styles and personalities are the Keirsey Temperament Sorter and the Myers-Briggs personality type. These are the ones with the four letter codes like INTP, ENFJ, and so on. Of course, there’s also astrology, enneagrams, and lots of others. We can debate the validity of the various methods, but it does seem clear that they sort people into categories based on

something

and that there are different sorts of people in the world.

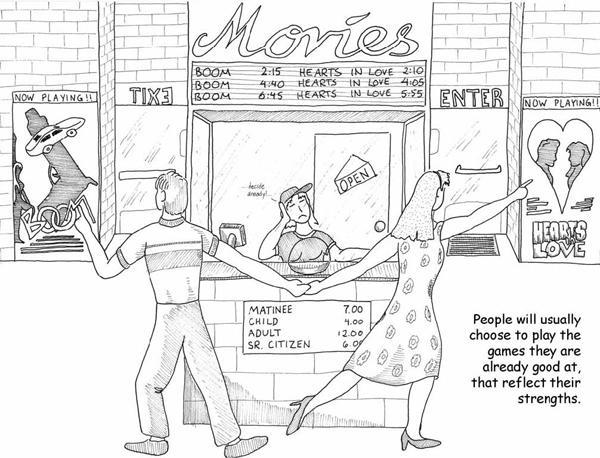

It’s clear that players tend to prefer certain types of games in ways that seem to correspond to their personalities.

It is equally clear that different people bring different experiences to the table that leave them with differing levels of ability in solving given types of problems. Even things that are more fundamental than that may change over time; for example, the levels of hormones such as estrogen and testosterone fluctuate pretty significantly over the course of a life, and it’s been shown that these affect personality.

What does this all mean for game designers? It means that not only will a given game be unlikely to appeal to everyone, but that it is probably impossible for it to do so. The difficulty ramp is almost certain to be wrong for many people, and the basic premises are likely to be uninteresting or too difficult for large segments of the population.

This may indicate a fundamental problem with games. Since they are formal abstract systems, they are by their very nature biased toward certain types of brains, just as books are biased. (Most book purchases in the U.S. are made by women, and half are made by individuals over the age of 45.)

For years now, the video game industry has struggled with the lack of appeal of games to the female audience. Many reasons have been advanced for this—the rampant sexism in video games, the lack of a retail channel that reaches the female demographic, the juvenile themes, the fact that there are relatively few female creators in the industry, the fact that the games focus on violence.

Perhaps the answer is simpler. Maybe games are more likely to appeal to young males because these players happen to have the sort of brain that works well with formal abstract systems. If so, you’d expect to see the following:

- Female players would gravitate toward games with simpler abstract systems and less spatial reasoning and more emphasis on interpersonal relationships, narrative, and empathy. They would also prefer games with simpler spatial topologies.

- There would be clear gender differences in play style between hardcore gamers of different genders. Males would focus on games emphasizing the projection of power and the control of territory, whereas females would select games that permit modeling behavior (such as multiplayer games) and do not demand strict hierarchies.

- As males aged, you’d expect them to slowly shift over to play styles similar to those of the women. Many of them might outright drop out of the gaming hobby. In contrast, older females likely wouldn’t drop out of gaming—if anything, their interest in them might actually sharpen after menopause.

- There would be fewer female gamers in general since no matter what, games are still about formal abstract systems at heart.

As it happens, we

do

see all of these in demographic data of game players (along with much more). Games may be doomed to be the province of 14-year-old boys because that’s what games select for.

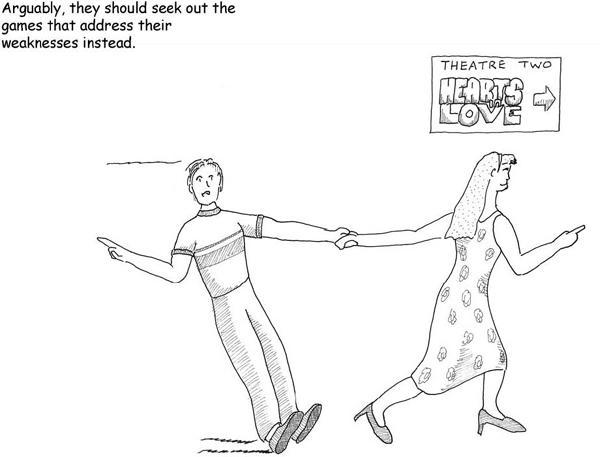

As games become more prevalent in society, however, we’ll likely see more young girls using the amazing brain-rewiring abilities of games to train themselves up—in other words, doubling down and reaching high levels of achievement on both sides of the fence. Recently, research was announced showing that girls who play “boys’ games” such as sports tend to break out of traditional gender roles years later, whereas girls who stick to “girls’ games” tend to adhere to the traditional stereotypes more strictly.

This argues pretty strongly that if people are to achieve their maximum potential, they need to do the hard work of playing the games they

don’t

get, the games that

don’t

appeal to their natures. Taking these on may serve as the nurture part of the equation, counterbalancing the brains that they were born with. The result would be people who move freely between worldviews, who bring a wider array of skills to bear on a given problem.

The converse trick, of training boys up, is harder for games to achieve because it does not play to the strength of games as a medium. Nonetheless, games should try. The thought that games are limited because of their fundamentally mathematical nature is somewhat depressing; it hasn’t stopped music from being a highly emotional medium, and language manages to convey mathematical thoughts, so there is hope for games yet.

Learning can be problematic. For one thing, it’s kind of hard work. Our brains may unconsciously direct us to learn, but if we’re pushed by parents, teachers, or even our own logical brains, we often resist most mightily.

When I was a kid taking math classes, teachers always made us write out proofs. We were good enough at algebra where we could look at a given problem and see the answer and then write it down, but it didn’t matter—we had to actually work it out:

x

2

+ 5 = 30

We weren’t allowed to just write x = 5. We had to write out:

∴ x

2

= 30 – 5

∴ x

2

= 25

∴ x = √25

∴ x = 5

We always thought this was stupid. If we could just look at the problem and see that x = 5, why the hell couldn’t we just write it down? Why go through the pesky process? All it did was slow us down!

Of course, the good reason is that multiplying -5 by -5 is also 25, and thus there are actually two answers. Skipping to the end, we’re more likely to forget that.

That doesn’t stop the human mind from wanting to take shortcuts, however.

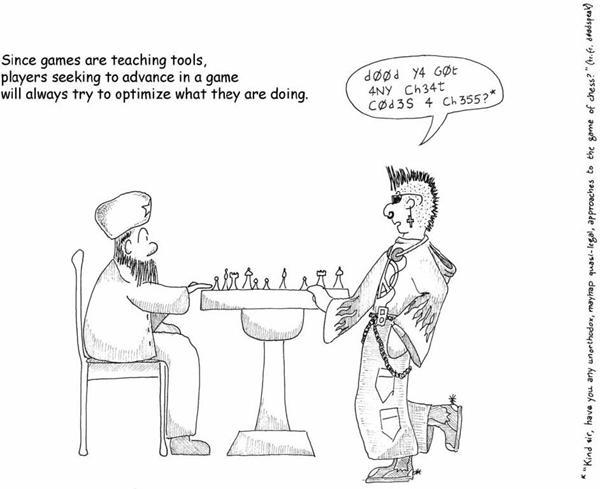

Once a player looks at a game and ascertains the pattern and the ultimate goal, they’ll try to find the optimal path to getting there. And one of the classic problems with games of all sorts is that players often have little compunction about violating the theoretical “magic circle” that encompasses games and makes them protected spaces in which to practice.

In other words, many players are willing to cheat.

This is a natural impulse. It’s not a sign of people being bad (though we can call it bad sportsmanship). It’s actually a sign of lateral thinking, which is a very important and valuable mental skill to learn. When someone cheats at a game, they may be acting unethical, but they’re also exercising a skill that makes them more likely to survive. It’s often called “cunning.”

Cheating is a long-standing tradition in warfare, where it is acknowledged as one of the most powerful and brilliant of all military techniques. “Let’s throw sand in our opponent’s eyes.” “Let’s attack by night.” “Let’s not charge out of the woods and ambush them instead.” “Let’s make them walk through the mud so we can shoot them full of arrows.” As one of the most important strategic adages has it, “If you cannot choose the battle, at least choose the battlefield.”