Theory of Fun for Game Design (13 page)

Read Theory of Fun for Game Design Online

Authors: Raph Koster

Tags: #COMPUTERS / Programming / Games

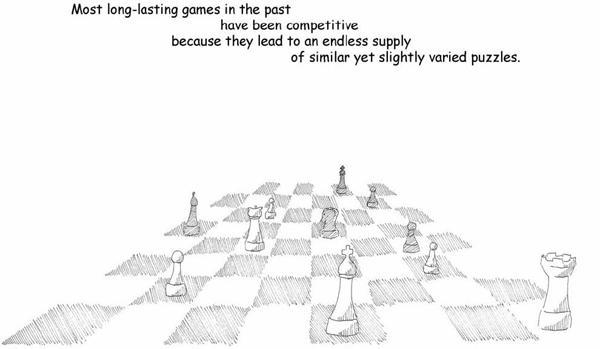

Looking at these elementary particles that make up ludemes, it’s easy to see why most games in history have been competitive head-to-head activities. It’s the easiest way to constantly provide a new flow of challenges and content.

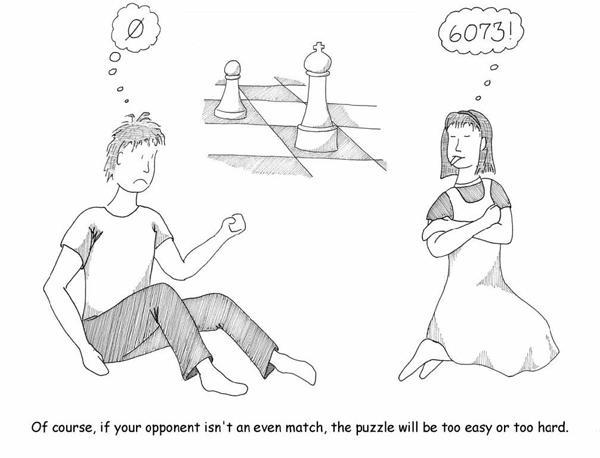

Historically, competitive game-playing of all sorts has tended to squeeze out the people who

most

need to learn the skills it provides, simply because they aren’t up to the competition and they are eliminated in their first match. This is the essence of the Mastery Problem. Because of this, a lot of people prefer games that take no skill. These people are definitely failing to exercise their brains correctly.

Not requiring skill from a player should be considered a cardinal sin in game design

. At the same time, designers of games need to be careful not to make the game demand too much skill. They must keep in mind that players are always trying to reduce the difficulty of a task. The easiest way to do that is to not play.

This isn’t an algorithm for fun, but it’s a useful tool for checking for the

absence

of fun because designers can identify systems that fail to meet all the criteria. It may also prove useful in terms of game critique. Simply check each system against this list:

- Do you have to prepare before taking on the challenge?

- Can you prepare in different ways and still succeed?

- Does the environment in which the challenge takes place affect the challenge?

- Are there solid rules defined for the challenge you undertake?

- Can the rule set support multiple types of challenges?

- Can the player bring multiple abilities to bear on the challenge?

- At high levels of difficulty, does the player

have

to bring multiple abilities to bear on the challenge? - Is there skill involved in using an ability? (If not, is this a fundamental “move” in the game, like moving one checker piece?)

- Are there multiple success states to overcoming the challenge? (In other words, success should not have a single guaranteed result.)

- Do advanced players get no benefit from tackling easy challenges?

- Does failing at the challenge at the very least make you have to try again?

If your answer to any of the above questions is “no,” then the game system is probably worth readdressing.

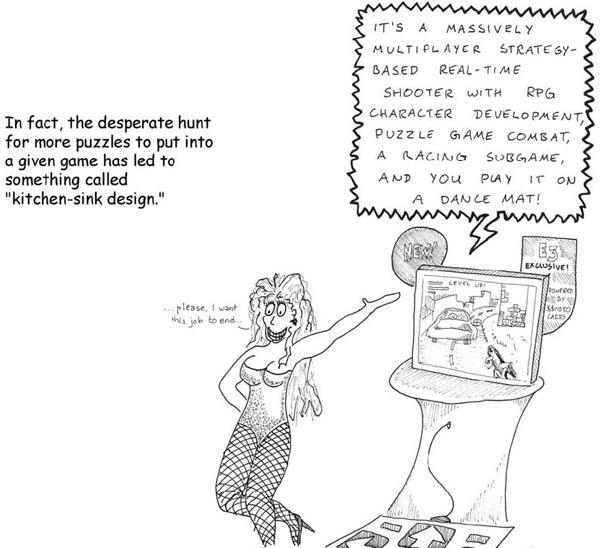

Game designers are caught in the Red Queen’s Race because challenges are meant to be surmounted. The result is that modern game designers have often taken the approach of piling more and more different types of challenges into one game. The number of ludemes reaches astronomical proportions. Consider that checkers consists of exactly two: “capture all the pieces” and “move one piece.” Now compare that to the last console game you saw.

Most classic games consist of relatively few systems that fit together elegantly. The entire genre of abstract strategy games is about elegant choice of ludemes. But in today’s world, many of the lessons we might want to teach might require highly complex environments and many moving parts—online virtual worlds spring to mind as an obvious example.

The lesson for designers is simple: A game is destined to become boring, automated, cheated, and exploited. Your sole responsibility is to know what the game is about and to ensure that the game teaches that thing. That one thing, the theme, the core, the heart of the game, might require many systems or it might require few. But

no system should be in the game that does not contribute toward that lesson

. It is the cynosure of all the systems; it is the moral of the story; it is the point.

In the end, that is both the glory of learning and its fundamental problem: Once you learn something, it’s over. You don’t get to learn it again.

The holy grail of game design is to make a game where the challenges are never ending, the skills required are varied, and the difficulty curve is perfect and adjusts itself to exactly our skill level. Someone did this already, though, and it’s not always fun. It’s called “life.” Maybe you’ve played it.

That hasn’t stopped us from trying all sorts of tactics to make games self-refreshing. You see, designing rule sets and making all the content is hard. Designers often feel proudest of designing good abstract systems that have deep self-generating challenges—games like chess and go and

Othello

and so on.

- “Emergent behavior”

is a common buzzword. The goal is new patterns that emerge spontaneously out of the rules, allowing the player to do things that the designer did not foresee. (Players do things designers don’t expect

all the time

, but we don’t like to talk about it.) Emergence has proven a tough nut to crack in games; it usually makes games easier, often by generating loopholes and exploits. - We also hear a lot about storytelling

. It’s easier to construct a story with multiple possible interpretations than it is to construct a game with the same characteristics. However, most games melded with stories tend to be Frankenstein monsters. Players tend to either skip the story or skip the game. - Placing players head-to-head

is also a common tactic, on the grounds that other players are an endless source of new content. This is accurate, but the Mastery Problem rears its ugly head. Players hate to lose. If you fail to match them up with an opponent who is very precisely of their skill level, they’ll quit. - Using players to generate content

is a useful tactic. Many games expect players to supply the challenges in various ways, ranging from making maps for a shooter game to contributing characters in a role-playing game.

But is this futile? I mean, all these designers are trying to expand the possibility space… …and all the players are trying to reduce it, just as fast as they can. You see, humans are wired in some interesting ways. If something has worked for us before, we’ll tend to do it again. We’re really very resistant to learning. We’re conservative at heart, and we grow more so as we age. You’ve perhaps heard the old saw, variously attributed to Clemenceau, Churchill, and Bismarck, “If a man isn’t liberal when he’s 20, he has no heart. If he’s not conservative when he’s 40, he has no brain.” Well, there’s a lot of truth to this. We grow more resistant to change as we age, and we grow less willing (and able) to learn.

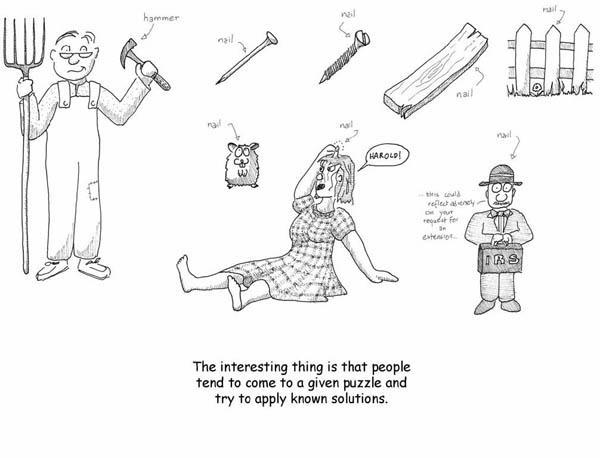

If we come across a problem we have encountered in the past, our first approach is to try the solution that has worked before, even if the circumstances aren’t exactly the same.

The problem with people isn’t that they work to undermine games and make them boring. That’s the natural course of events. The real problem with people is that

…even though our brains feed us drugs to keep us learning……even though from earliest childhood we are trained to learn through play……even though our brains send incredibly clear feedback that we should learn throughout our lives…PEOPLE ARE LAZY

.

Look at the games that offer the absolute greatest freedom possible within the scope of a game setting. In role-playing games there are few rules. The emphasis is on collaborative storytelling. You can construct your character any way you want, use any background, and take on any challenge you like.

And yet, people choose the

same

characters to play, over and over. I’ve got a friend who has played the big burly silent type in literally dozens of games over the decade I have known him. Never once has he been a vivacious small girl.

Different games appeal to different personality types, and not just because particular problems appeal to certain brain types. It’s also because particular

solutions

appeal to particular brain types, and when we’ve got a good thing going, we’re not likely to change it. This is not a recipe for long-term success in a world that is constantly changing around us. Adaptability is key to survival.

Much is made of cross-gender role-play in online settings. When you look at it in this light, it’s clearly because a given gender presentation is a

solution choice

—a tool the player is using to solve problems presented by the online setting. It might be because the gender presentation is a good way to meet like-minded people. Males choosing female avatars may be signaling something about their preference for the company of other empathizing brains, for example.

Sticking to one solution is not a survival trait anymore. The world is changing very fast, and we interact with more kinds of people than ever before. The real value now lies in a wide range of experiences and in understanding a wide range of points of view. Closed-mindedness is actively dangerous to society because it leads to misapprehension. And misapprehension leads to misunderstanding, which leads to offense, which leads to violence.

Consider the hypothetical case where every player of an online role-playing game gets exactly two characters: one male and one female. Would the world be more or less sexist as a result?