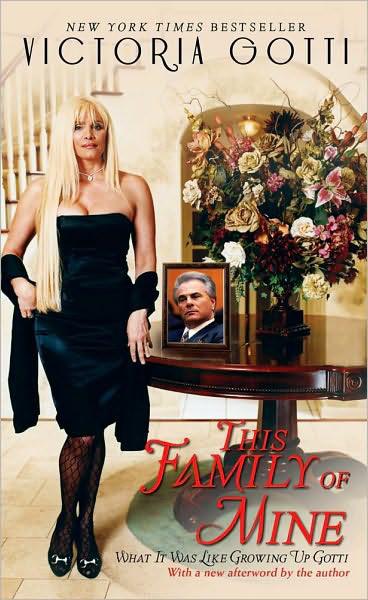

This Family of Mine: What It Was Like Growing Up Gotti

Read This Family of Mine: What It Was Like Growing Up Gotti Online

Authors: Victoria Gotti

Tags: #Non-Fiction

Dad tried to hide from his children the fact that he didn’t have a conventional job.

There were various fabrications, the most common being his role as the powerful head of a local construction company. In fact, every day when he left for “work,” at the oddly late hour of 10 or 11

A.M.

, he would tell us about some new project he was developing: a skyscraper one month, a three-story beach house or a suite of offices the next month. I remember how he used to bounce me on his knee and answer all of my silly questions about the construction trade.

I was fascinated with creativity—more specifically, building things from scratch. I was quite impressionable and for the most part believed just about anything Dad would tell me. For the longest time it never occurred to me to ask my father why he always wore a suit when he was going off to a construction site. I think back on it now and laugh at the notion of Dad ten stories up, checking out I-beams in his sharkskin suit, Merino wool turtleneck, and Italian leather shoes. He couldn’t possibly have looked more out of place.

THIS FAMILY OF MINE

the

New York Times

bestselling memoir from

VICTORIA GOTTI

This title is also available from Simon & Schuster Audio and as an eBook

Pocket Star Books

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright © 2009 by Victoria Gotti

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Pocket Books Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Pocket Star Books paperback edition January 2011

POCKET STAR BOOKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or [email protected].

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at

www.simonspeakers.com

.

All photos courtesy of author’s personal collection.

Cover design by John Vairo Jr.

Jacket photograph © Erin Patrice O’Brien/Corbis

Photograph of John Gotti © AP/Richard Drew

Picture frame © Stephen Shepherd/Photonica/Getty Images

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN: 978-1-4391-5451-9

ISBN 978-1-4391-6322-1 (ebook)

As always I dedicate this book to my family:

For better or worse—in good times and in bad,

I will always love you all.

To my three sons, Carmine, John and Frank—

you can’t imagine the love I feel for you.

June 15, 2002

QUEENS, NEW YORK

The gates separating St. John’s Cemetery in Middle Village, Queens, from the living, breathing outside world are appropriately impressive—a baroque expanse of wrought-iron swirls seems to cascade from heaven itself, serving as an unmistakable line between life and the afterlife. Within these forty acres rest some of the most famous and infamous denizens of New York society, a wildly eclectic group that includes the controversial artist Robert Mapplethorpe, the bodybuilder Charles Atlas, numerous politicians, and Mafia dons Joseph Colombo, Carlo Gambino, and Vito Genovese. Death plays no favorites, makes no distinction. In the end, despite our differences, we are all the same. And now this was to be the final resting place of my father, John Gotti.

More than one hundred cars snaked along the roads of the

cemetery, in neat and orderly fashion. Mercedes, Cadillacs, and a small fleet of Lincoln Town Cars—all black, all filled to capacity—followed closely behind an overstuffed flower car; at the very front of the line was a glistening black hearse.

The funeral procession meandered down the winding, grassy road, until the hearse reached its destination. Then, like a row of dominoes, car after car followed suit.

As we pulled up to the chapel, a small old man with hollow eyes and a white beard emerged from the caretaker’s cottage and scurried across a narrow path. He fumbled for a set of keys in his pocket before unlocking the mammoth stained-glass doors.

One by one, mourners emerged from their cars and filed somberly into the chapel. I was accompanied by my three sons—Carmine, John, and Frank—my sister Angel, and my niece Victoria, Angel’s daughter. I rode in one of ten family cars. As usual, Angel and I were on the same wavelength, with similar thoughts racing through our minds. When the car stopped, neither of us moved for the door—whether through fear or dread, it was almost as if we were paralyzed, both having been raised by the same man and following the same traditions for years. Neither of us could bear the thought of saying good-bye to Daddy. Meanwhile, everyone was waiting outside the car for us to join them before moving inside. Sickeningly, but predictably, a swarm of paparazzi had assembled not more than fifty feet across the road, buzzing in anticipation of their money shot. We’d been in the public eye long enough to know the rules of the game—there was no way we were going to do anything that would attract greater attention from the photographers.

The chapel was lit with flickering white votive candles and ancient Tiffany-style lamps above providing meager illumination, which added to the funereal ambience. Gray and musty, the space

felt less like a chapel than an antiquated living room. In the back of the chapel, the floors were covered with worn green carpet, the walls bore old-fashioned floral-print wallpaper. Dark wood antique furniture was scattered around the room: a sofa here, a chair there, with flimsy beige slipcovers protecting most pieces.

As gospel music issued from overhead speakers, the mourners continued to file in; the immediate family members took their seats first in a row of narrow pews at the front of the chapel, followed by relatives, friends, and acquaintances. I sat to the right of the first row, sandwiched between my mother and sister. Dad’s casket, made of mahogany and trimmed in gold leaf, was a mere three feet in front of us, and being so close to him—knowing that his body was inside that wooden box, and would soon be buried forever—was almost more than I could bear. I felt faint. It had been more than thirteen years since I had been able to hug my father or even touch him; for thirteen years, six months, and four days, he had been imprisoned at a super-max federal correctional facility in Marion, Illinois. Our visits with him only allowed for conversation, laughter, or tears, our bodies always separated by a wall of Plexiglas. Now here he was, so close, but still in a prison, still beyond my reach. I don’t know which was worse for Dad (or for me), jail or death.

Tears soon came freely as a flood of anguish, sadness, and regret washed over me. I had not told him nearly enough times just how much I loved and needed him, and just how important he was to me. As I rocked back and forth, sobbing, my mother leaned over and put her arm around my shoulder.

“It’ll be all right, baby,” she said.

I nodded, held her hand. Hers was a warm and maternal gesture, but I knew in my heart that nothing would be all right ever again. The backbone of our family was gone—and the prospect

of my father’s absence both saddened and terrified us. The fear in Mom’s eyes was unmistakable, just as it had been the night before, when I’d found her pacing the floor of her master bedroom at 3

A.M

.

“I can’t imagine my life without him,” she had whispered.

Her anxiety was understandable and shared by each of us. My dad’s strong sense of tradition and the importance he placed on family had produced an extraordinarily tight clan. We had gathered at least once a week for Sunday dinners of pasta and delicious stuffed meats, a tradition in our family stretching back for more than three decades. It was Dad’s favorite day of the week, when we all came together in one house to laugh and swap stories over a family meal. It was heaven on earth for my father: a few hours when he wasn’t troubled by business or legal matters, when his children and grandchildren surrounded him, eating and smiling, for hours on end. These were his favorite moments. So important were these gatherings to my father that even after he went to prison, he made sure we continued the tradition. It was one of his last wishes before he was sent away. For the most part, responsibility for hosting Sunday dinner would fall on my shoulders, and I happily accepted the job.

“No matter what happens,” Dad would always say during our conversations on a visit, or on the telephone while he was at Marion, “you have to honor this tradition.”

It’s strange how something as simple as a Sunday dinner weighed on my mind at that moment. Dad was gone, and with him perhaps some piece of the obligation (or at least the urgency) to continue our Sunday tradition. I knew we would never again come together again as a complete family, that the tradition had come to an end. It just exacerbated the grief I felt. Without Dad to pull us together, I knew there was a chance that the Gottis would quickly splinter.

“Don’t get too caught up in your own lives to remember the importance of being together,” he’d said shortly before passing, in the last letter I’d received from him.

I gazed at the casket, memories of decades of Gotti family tradition filling my head and my heart.

We’ll try, Dad

.

O

NCE FAMILY AND

close friends were seated, an additional crowd of mourners was granted access and permitted to stand in the back of the chapel. The room was filled to capacity, and yet hundreds of mourners, some whom I knew very well, others not at all, were left outside.

The chapel fell silent as the priest bowed his head and began to speak.

“Our Father, who art in heaven . . .”

His voice resonated in the chapel, and yet his words barely registered, I was so lost in thought. Outside, a thunderstorm had moved in. With the shift in weather came flashes of lightning, crackling thunder, and then rain, pounding against the chapel windows. Although the room was full of people, I suddenly felt alone. In the throes of grief, I wanted to scream. I wanted the ceremony to stop. But I hadn’t the strength even for that. After two days of crying, I could barely muster the energy to speak.

“Thy kingdom come, thy will be done . . .”

As the priest continued, mourners from the back of the room were invited to approach my father one last time. As they passed by, each person gently placed a single red long-stemmed rose they had been given on the top of the casket.

It was a solemn, unifying ritual, bonding mourners from a broad spectrum of social classes. Many of these men and women had attended my father’s wake and had a story to tell. The elderly,

homeless lady from Ozone Park, Queens, who between sobs had told me of Dad’s generosity, how he had regularly given her money for over twenty years. The sanitation worker who claimed Dad had helped put his only son through college. The housewife from Rockaway Boulevard who credited Dad with saving her daughter’s life after a grim diagnosis of leukemia; he had arranged for a pioneering oncologist from Boston to oversee the young girl’s care. Then there was the affluent, elderly man—a former CEO of a major corporation—who tearfully divulged an unpaid (and unpayable) debt to my father. Dad apparently had helped the man face and eventually overcome a “troublesome and dangerous” gambling addiction. The Ivy League kid, a nineteen-year-old freshman, with his parents in tow, who credited Dad with saving his life after an illadvised and dangerous boyhood prank had nearly sent him away to prison. The young man’s parents, a middle-aged couple from Italy who had emigrated a decade earlier in search of a better life for their only son, choked back tears as they told the story of how my father had arranged for a top-flight defense attorney to represent their son—although not until Dad had “scared the kid straight.”