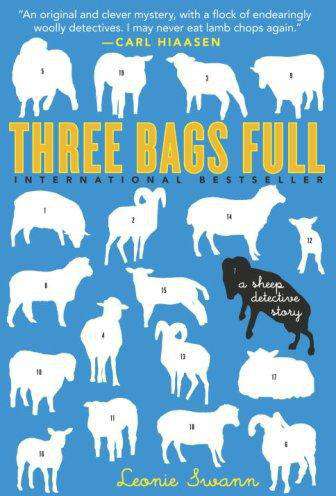

Three Bags Full

Authors: Leonie Swann

Tags: #Shepherds, #Sheep, #Villages, #General, #Fiction, #Murder, #Humorous, #Crime, #Mystery & Detective, #Ireland

Contents

4 Mopple Squeezes Through a Gap

7 Sir Ritchfield Behaves Oddly

11 Othello and a Case of Mistaken Identity

15 Zora Learns Something About the Grim Reaper

17 Cordelia Knows Some Useful Words

For M.,

without whom the whole story would never have come out

The trail wound here and there as the sheep had willed in the making of it.

Stephen Crane,

Tales of Adventure

DRAMATIS OVES

in order of appearance

M | has a very good sense of smell and is proud of it. |

S | the lead ram, not as young as he used to be, rather hard of hearing and has a poor memory, but his eyes are still good. |

M | the cleverest sheep in the flock, maybe the cleverest sheep in Glennkill, quite possibly the cleverest sheep in the whole world. Has an enquiring mind, never gives up, sometimes feels a sense of responsibility. |

H | a lively young sheep, doesn’t always think before she speaks. |

C | the woolliest sheep in the flock. |

M | the memory sheep: once he has seen something he never forgets it. A very stout Merino ram with round spiral horns, almost always hungry. |

O | a black Hebridean four-horned ram with a mysterious past. |

Z | a Blackface sheep, with a good head for heights, the only ewe with horns in George Glenn’s flock. |

R | a young ram whose horns are still rather short. |

L | the fastest sheep in the flock, a pragmatic thinker. |

S | a mother ewe. |

A LAMB | who has seen something strange. |

C | likes unusual words. |

M | Sir Ritchfield’s twin brother, a legendary ram who disappeared. |

M | a naïve young sheep. |

THE WINTER LAMB | a difficult lamb, a troublemaker. |

W | the second most silent sheep in the flock; no one minds that. |

G | a very odd sheep. |

F | correctly thinks himself clever. |

1

Othello Boldly Grazes Past

“He was healthy yesterday,” said Maude. Her ears twitched nervously.

“That doesn’t mean anything,” pointed out Sir Ritchfield, the oldest ram in the flock. “He didn’t die of an illness. Spades are not an illness.”

The shepherd was lying in the green Irish grass beside the hay barn, not far from the path through the fields. He didn’t move. A single crow had settled on his woolly Norwegian sweater and was studying his internal arrangements with professional interest. Beside the crow sat a very happy rabbit. Rather farther off, close to the edge of the cliff, the sheep were holding a meeting.

They had kept calm that morning when they found their shepherd lying there so unusually cold and lifeless, and were extremely proud of it. In the first flush of alarm, naturally there had been a few frantic cries of “Who’s going to bring us hay now?” and “A wolf! There’s a wolf about!,” but Miss Maple had been quick to quell any panic. She explained that here on the greenest, richest pasture in all Ireland only idiots would eat hay in midsummer anyway, and even the most sophisticated wolves didn’t drive spades through the bodies of their victims. For such a tool was undoubtedly sticking out of the shepherd’s insides, which were now wet with dew.

Miss Maple was the cleverest sheep in all Glennkill. Some even claimed that she was the cleverest sheep in the world, but no one could prove it. There was in fact an annual Smartest Sheep in Glennkill contest, but Maple’s extraordinary intelligence showed in the very fact that she did not take part in such competitions. The winner, after being crowned with a wreath of shamrock (which it was then allowed to eat), spent several days touring the pubs of the neighboring villages, and was constantly expected to perform the trick that had erroneously won it the title, eyes streaming as it blinked through clouds of tobacco smoke, with the customers pouring Guinness down its throat until it couldn’t stand up properly. Furthermore, from then on the winning sheep’s shepherd held it responsible for each and every prank played out at pasture, since the cleverest animal was always going to be the prime suspect.

George Glenn would never again hold any sheep responsible for anything. He lay impaled on the ground beside the path while his sheep wondered what to do next. They were standing on the cliffs between the watery-blue sky and the sky-blue sea, where they couldn’t smell the blood, and they did feel responsible.

“He wasn’t a specially good shepherd,” said Heather, who was still not much more than a lamb and still bore George a grudge for docking her beautiful tail at the end of last winter.

“Exactly!” said Cloud, the woolliest and most magnificent sheep ever seen. “He didn’t appreciate our work. Norwegian sheep do it better, he said! Norwegian sheep give more wool! He had sweaters made of foreign wool sent from Norway—it’s a disgrace! What other shepherd would insult his own flock like that?”

There ensued a discussion of some length between Heather, Cloud, and Mopple the Whale. Mopple the Whale insisted that you judged a shepherd’s merits by the quantity and quality of the fodder he provided, and in this respect there was nothing, nothing whatsoever, to be said against George Glenn. Finally they agreed that a good shepherd was one who never docked the lambs’ tails; didn’t keep a sheepdog; provided good fodder and plenty of it, particularly bread and sugar but healthy things too like green stuff, concentrated feed, and mangel-wurzels (for they were all very sensible sheep); and who clothed himself entirely in the products of his own flock, for instance an all-in-one suit made of spun sheep’s wool, which would look really good, almost as if he were a sheep himself. Of course it was obvious to them all that no such perfect being was to be found anywhere in the world, but it was a nice idea all the same. They sighed a little, and were about to scatter, pleased to think that they had cleared up all outstanding questions.

So far, however, Miss Maple had taken no part in the discussion. Now she said, “Don’t you want to know what he died of?”

Sir Ritchfield looked at her in surprise. “He died of that spade. You wouldn’t have survived it either, a heavy iron thing like that driven right through you. No wonder he’s dead.” Ritchfield shuddered slightly.

“And where did the spade come from?”

“Someone stuck it in him.” As far as Sir Ritchfield was concerned, that was the end of the matter, but Othello, the only black sheep in the flock, suddenly began taking an interest in the problem.

“It can only have been a human who did it—or a very large monkey.” Othello had spent his youth in Dublin Zoo and never missed an opportunity to mention it.

“A human.” Maple nodded, satisfied. “I think we ought to find out what kind of human. We owe old George that. If a fierce dog took one of our lambs, he always tried to find the culprit. Anyway, he was our shepherd. No one had a right to stick a spade in him. That’s wolfish behavior. That’s murder.”

Now the sheep were feeling alarmed. The wind had changed, and the smell of fresh blood was drifting toward the sea.

“And when we’ve found the person who stuck the spade in,” asked Heather nervously, “then what?”

“Justice!” bleated Othello.

“Justice!” bleated the other sheep. And so it was decided that George Glenn’s sheep themselves would solve the wicked murder of their shepherd.

First Miss Maple went over to examine the body. She did it reluctantly: in the summer sun of Ireland, George had already begun to smell bad enough to send a shudder down any sheep’s spine.

She started by circling the shepherd at a respectful distance. The crow cawed and fluttered away on black wings. Maple ventured closer, inspected the spade, sniffed George’s clothes and face. Finally—as the rest of the flock, huddling together at a safe distance, held their breaths—she even stuck her nose in the wound and rooted around. At least, that was what it looked like from where the others stood. She came back to them with blood on her muzzle.

“Well?” asked Mopple, unable to stand the suspense any longer. Mopple never could stand strain of any kind for long.

“He’s dead,” replied Miss Maple. She didn’t seem to want to say any more just now. Then she looked back at the path. “We have to be prepared. Sooner or later humans are going to turn up here. We must watch what they do. And we’d better not all stand around in a crowd; it looks suspicious. We ought to act naturally.”

“But we are acting naturally,” objected Maude. “George is dead. Murdered. Should we be grazing right beside him where the grass is spattered with his blood?”

“Yes, that’s exactly what we ought to be doing.” The black figure of Othello came between them. His nostrils contracted as he saw the horrified faces of the others. “Don’t worry, I’ll do it. I spent my youth near the carnivores’ enclosure. A little more blood won’t kill me.”

At that moment Heather thought what a particularly bold ram Othello was. She decided to graze near him more often in future—though not until George had been taken away and fresh summer rain had washed the meadow clean, of course.

Miss Maple decided who would keep watch where. Sir Ritchfield, whose eyesight was still good in spite of his advanced age, was stationed on the hill. You could see across the hedges to the paved road from there. Mopple the Whale had poor eyes but a good memory. He stood beside Ritchfield to remember everything the old ram saw. Heather and Cloud were to watch the path that ran through the meadow: Heather took up her post by the gate nearest to the village; Cloud stood where the path disappeared into a dip in the ground. Zora, a Blackface sheep who had a good head for heights, stationed herself on a narrow rocky ledge at the top of the cliff to keep watch on the beach below. Zora claimed to have a wild mountain sheep in her ancestry, and when you saw how confidently she moved above the abyss you could almost believe it.

Othello disappeared into the shadow of the dolmen, near the place where George lay pinned to the ground by the spade. Miss Maple did not keep watch herself. She stood by the water trough, trying to wash the traces of blood off her nose.

The rest of the sheep acted naturally.

A little later Tom O’Malley, no longer entirely sober, came along the footpath from Golagh to Glennkill to favor the local pub with his custom. The fresh air did him good: the green grass, the blue sky. Gulls pursued their prey, calling, wheeling in the air so fast that it made his head spin. George’s sheep were grazing peacefully. Picturesque. Like a travel brochure. One sheep had ventured particularly far out, and was enthroned like a small white lion on the cliff itself.

“Hey there, little sheep,” said Tom, “don’t you take a tumble now. It’d be a shame for a pretty thing like you to fall.”

The sheep looked at him with disdain, and he suddenly felt stupid. Stupid and drunk. But that was all in the past now. He’d make something of himself. In the tourism line. That was it, the future of Glennkill lay in the tourist trade. He must go and talk it over with the lads in the pub.

But first he wanted to take a closer look at the fine black ram. Four horns. Unusual, that. George’s sheep were something special.

However, the black ram wouldn’t let him close enough, and easily avoided Tom’s hand without even moving much.

Then Tom saw the spade.

A good spade. He could do with a spade like that. He decided to consider it his spade in future. For now he’d hide it under the dolmen, and come back to fetch it after dark. He didn’t much like the idea of going to the dolmen by night—people told tales about it. But he was a modern man, and this was an excellent spade. When he grasped the handle, his foot struck something soft.

It was a long time since Tom O’Malley had attracted such an attentive audience in the Mad Boar as he did that afternoon.

Soon afterward, Heather saw a small group of humans running along the path from the village. She bleated—a short bleat, a long bleat, another short bleat—and Othello emerged rather reluctantly from under the dolmen.

The group was led by a very thin man whom the sheep didn’t know. They looked hard at him. The leader of the flock is always important.

Behind him came the butcher. The sheep held their breath. Even the scent of him was enough to make any sheep go weak at the knees. The butcher smelled of death. Of screams, pain, and blood. The dogs themselves were afraid of him.

The sheep hated the butcher. And they loved Gabriel, who came right behind him, a small man with a shaggy beard, and a slouch hat, walking fast to keep up with the mountain of flesh just ahead. They knew why they hated the butcher. They didn’t know why they loved Gabriel, but he was irresistible. His dogs could do the most amazing tricks. He won the sheepdog trials in Gorey every year. It was said he could talk to the animals, but that wasn’t true. At least, the sheep didn’t understand it when Gabriel spoke Gaelic. But they felt touched, flattered, and finally seduced into trotting trustfully up to him when he passed their meadow on his way along the path through the fields.

Now the humans had almost reached the corpse. The sheep forgot about looking natural for a moment and craned their necks to see. The thin man leading the humans stopped several lamb’s leaps away from George, as if rooted to the ground. His tall figure swayed for a moment like a branch in the wind, but his eyes were fixed, sharp as pins, on the spot where the spade stuck out of George’s guts.

Gabriel and the butcher stopped a little way from the body too. The butcher looked at the ground for a moment. Gabriel took his hands out of his trouser pockets. The thin man removed his cap.

Othello boldly grazed his way past them.

Then, puffing and panting, her face scarlet and her red hair all untidy, Lilly came along the path too, and with her a cloud of artificial lilac perfume. When she saw George she uttered a small, sharp scream. The sheep looked at her calmly. Lilly sometimes came to their meadow in the evening and uttered those short, sharp screams at the least little thing—when she trod in a pile of sheep droppings, when her skirt caught on the hedge, when George said something she didn’t like. The sheep were used to it. George and Lilly often disappeared to spend a little time inside the shepherd’s caravan. Lilly’s peculiar little shrieks didn’t bother them anymore.

But then the wind suddenly carried a pitiful, long-drawn-out sound across the meadow. Mopple and Cloud lost their nerve and galloped up the hill, where they felt ashamed of themselves and tried to look natural again.

Lilly fell to her knees right beside the body, ignoring the grass, which was wet with last night’s rain. She was the person making this dreadful noise. Like a couple of confused insects, her hands wandered over the Norwegian sweater and George’s jacket, and tugged at his collar.

The butcher was suddenly beside her, pulling her roughly back by her arm. The sheep held their breath. The butcher had moved as quickly as a cat. Now he said something, and Lilly looked at him with tears in her eyes. She moved her lips, but not a sound was heard in the meadow. The butcher said something in reply, then he took Lilly’s sleeve and drew her aside. The thin man immediately began talking to Gabriel.

Othello looked round for help. If he stayed close to Gabriel, he would miss whatever was going on between the butcher and Lilly—and vice versa. None of the sheep wanted to get close to the body or the butcher, which both smelled of death. They preferred to concentrate on the job of looking natural.

Miss Maple came trotting along from the water trough and took over observation of the butcher. There was still a suspicious red mark on her nose, but as she had been rolling in the mud she now just looked like a very dirty sheep.

“…ridiculous fuss,” the butcher was just saying to Lilly. “And never mind making a spectacle of yourself. You’ve got other worries now, sweetheart, believe you me.” He had taken her chin in his sausagelike fingers and raised her head slightly so that she had to look straight into his eyes.

“Why would anyone suspect me?” she asked, trying to free her head. “George and I got along fine.”