Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig (6 page)

Read Three Lives: A Biography of Stefan Zweig Online

Authors: Oliver Matuschek

At the time of his marriage and the birth of his two sons at the beginning of the 1880s, Moriz Zweig was just starting out as an industrialist, but by now, twenty years later, he had amassed a considerable fortune through his business. Not only was the family reputed to be wealthy—it actually was wealthy. And no less important was the fact that it was recognised as such by its social equals. No doubt this made it easier to decide to let Stefan study philosophy and the history of literature.

Dared they hope that their writer son would achieve great things? Excessive optimism was something else that ran counter to the Zweig family tradition …

NOTES

1

Zweig F 1947, p 23.

2

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 55.

3

Ernst Benedikt: Erinnerungen, p 2.

4

Salzburg 1961, Cat No 10

5

Czeike 1992 ff, see under “Zweig, Stefan”.

6

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 58 f.

7

Alfred Zweig: Familiengeschichte. No trace of the poem manuscript has been found.

8

Stefan Zweig to Georg Ebers, 10th March 1897. In: Briefe I, p 13.

9

Stefan Zweig to Karl Emil Franzos, 22nd June 1900. In: Briefe I, p 19.

10

Stefan Zweig to Karl Emil Franzos, 3rd July 1900. In: Briefe I, p 20 f.

11

Stefan Zweig to Karl Emil Franzos, 18th February 1898. In: Briefe I, p 14 f.

12

Zweig GW Welt von Gestern, p 75.

13

Zweig F 1947, p 23.

14

Ernst Benedikt: Erinnerungen, p 2.

15

Alfred Zweig: Familiengeschichte.

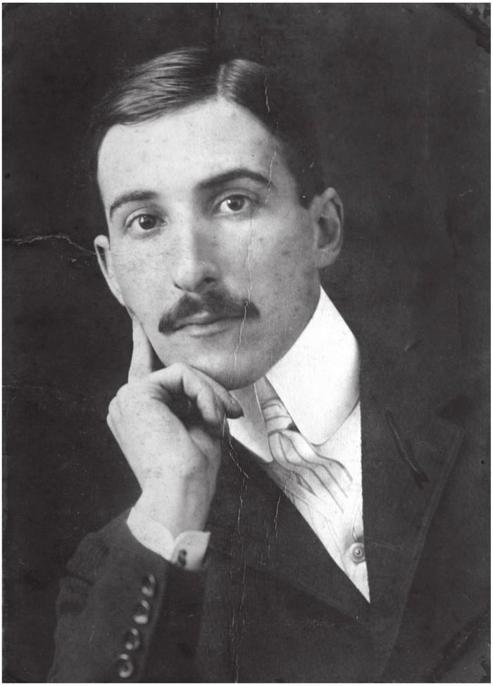

Stefan Zweig circa 1904

I loved writers from their books: distance and death lent them an aura of beauty. I knew a few contemporary writers: they disappointed by their proximity and their frequently repellent way of life …

1

Erinnerungen an Émile Verhaeren 1917

T

HE DAY AFTER

he took his final school exams on 12th July 1900, Zweig wanted to put school behind him as quickly as possible. He had enrolled at the University of Vienna for the coming semester, to study philosophy and the history of literature. Such was his desire to get away that he planned to use the money his parents had given him after passing his final exams to go travelling (although at home he only talked vaguely about “a trip into the country”). In fact he hoped to travel as far as Berlin, or even France, but neither plan would come to pass that year. Instead the dutiful son accompanied his parents to Marienbad, as he did every summer, and then travelled on with them to the spa resort of Bad Ischl in the Austrian Salzkammergut.

The destination mattered less than getting away. With every kilometre that he put between himself and Vienna, his schooldays just ended became a lost world, a “world of yesterday”. It was not just the grammar school that Zweig left behind, but also his classmates. In later years he had lost touch with nearly all of them. This was partly because most of them had to concern themselves in future with matters other than literature and the fine arts, even if they had been busily writing poems themselves just a short while ago and dreaming of careers far removed from banking or the law. But also because Zweig, in his latter years at school, struck many of his classmates as more mature than they felt themselves to be. This set him clearly apart from them, though very possibly he didn’t want to be different, and wasn’t really aware of being different—conspicuous vanity or priggishness were not among his failings. But the seriousness and persistence with which he applied himself to his literary endeavours clearly left a deep impression. As Ernst Benedikt recalls: people didn’t think they had anything more to give him because he appeared so mature and self-sufficient in his last years at school.

If the summer vacation with his parents failed to bring Stefan the feeling of release he longed for, the second stage of his “escape” from school and his former life proved more successful. Back in Vienna, he was granted a heartfelt wish and finally allowed to move into his own room. It was not a proper apartment as such, but it was a small student room, and it was furnished. Large and well-appointed as the parental apartment was, he had hitherto only had one room of his own—which he also had to share with his brother. At least during his last two years at school he had had the room to himself for most of the time, since Alfred was away from Vienna on technical courses and work experience, only returning home in the holidays.

Over the following semesters Zweig changed his rooms several times. A glance at a map of the city shows that all the rooms lay within a very short distance of the University, which means that none of them was far from his parents’ apartment. Here he collected his mail and stayed to dinner on a fairly regular basis.

But this new-won freedom did not alter the fact that Zweig continued to be pained by the way he and his contemporaries were treated by adults. He notes with irritation, for example, that even on the eve of their majority, which in those days was reached at the age of twenty-four, he and his schoolmates and fellow students were far too often fobbed off by parents, teachers and most of their so-called “elders and betters” with a dismissive “You’re not old enough to understand that”. Seemingly trivial things such as the separate hotel dining rooms for children and adults referred to earlier, which from an early age he had regarded as an insufferable affront to his person, had made him acutely sensitive to humiliations of this sort. “Adults never tired of telling young people that they were not ‘mature’ enough yet, that they did not understand anything, and that their place was to listen and learn—but never to speak, let alone argue.”

2

Zweig now found himself in a strangely contradictory position. On the one hand the adult world seemed to close ranks against him the older he got, while on the other the same schoolboy and undergraduate was treading in the footsteps of the great writers, as his first publications in respected journals were soon to demonstrate. Happily these same publications would lead to Stefan Zweig’s breakthrough as a writer. Not yet in the wider public domain, but in another important arena—the parental home.

If we are to believe Zweig’s own account, he must have been a virtually unknown figure at university. In his memoirs he draws a deliberate contrast

between his student years and his time at school. He still had a timetable, but there was no compulsory attendance. So it was a matter of making the most effective use of the time he could free up from his schedule to pursue his own reading and work on his own writings. However, Zweig was not such an absentee student as he later liked to make out. Various comments from his student years indicate that he was engaging seriously with the syllabus.

It is not surprising, however, that he was unwilling to sacrifice his own work to his studies. Now that he no longer had to hide behind pseudonyms, Zweig could at last get to work on a plan that he had been mulling over for some time. Every piece published in well-regarded newspapers and journals was cause for gratification: how much more momentous it would be to see his own poems published in book form! In March 1900, even before he sat his school-leaving exams, he had written to Franzos to sound him out about the possibility of issuing such a book of poems under his own imprint. He wrote to other publishing houses as well, of course, asked around, compared and assessed their output. A not unimportant consideration for him was to have his first work published, if at all possible, by a company that already had some important writers in its catalogue. He also attached great importance to the outward appearance of the book, an aspect for which he had by now developed a certain eye. As well as a modern jacket design he wanted to see graphic embellishments on the individual pages. And an uncluttered layout was very important to him—putting more than one poem on a page seemed to him completely inconceivable. In the end he found what he was looking for in the Berlin publishers Schuster & Loeffler. They were willing to take on a volume of poetry and to produce it in line with his ideas.

As well as beautifully designed books, this company also published the journal

Die Insel

, to which some authors of the older generation contributed, but also young poets like Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Rainer Maria Rilke. It was an added bonus to think that if one were published under this imprint one might hope to be ranked alongside rising talents such as these. And so in the spring of 1901 Stefan Zweig’s first published book appeared under the title

Silberne Saiten

[

Silver Strings

], taken from a line in his poem

Nocturno

. The jacket design and graphics were the work of Hugo Steiner. All we know about the preparation of the manuscript for printing is that Zweig went through a process of ruthless selection, trying to sift out from the hundreds of poems he had written those that seemed the most successful

in themselves, and that also fitted in best with the overall tone of the work. Much silvery moonlight shone through these verses, the scent of flowering blossoms was overpowering, and longing was an ever-present theme. Two decades later Zweig looked back on what he had written then with a sternly critical eye, but he also saw it as an important stylistic exercise:

I wrote poems throughout those empty years at school—or so they seemed to me—long before I had experienced anything, composing verses full of passion to women before I knew what it was to be erotically aroused; and as I wrote a lot of poetry back then the result was an early familiarity with different forms, a remarkably polished ease of versified expression, and a facility of production that I lost a long time ago, as I learnt to recognise the things of true value.

3

One can imagine the feverish excitement with which Zweig looked forward to the day when he held the finished book in his hands. When that day came, the anticipation immediately started to build towards the next climax—how would the book be received by the critics? In that golden age of lyric poetry it would have been easy, as a newly published poet, to get lost in the crowd. But the book was reviewed in all the leading newspapers. Zweig carefully glued all the reviews of his first work—over forty of them—onto cardboard, writing the source reference and date on each card and filing them in a card index. There was almost unanimous agreement among the critics—this was the work of a talented young man. It is interesting to note that nearly all of them saw the delicate sensitivity of the poetry as a direct reflection of the author’s own character. One reviewer cited the passage “A lad who wandered weary through the day, his eyes wide and filled with dreamy longing …” and claimed that this was “nothing more or less than a self-portrait”.

4

Leonard Adelt wrote in

Die Zeit

: “The raw passion that sweeps human life along, so brutal and yet so splendid, rages not in the poetry of Stephan Zweig. Zweig is too delicate a nature, his soul so delicately strung that the most hushed tones of feeling reverberate within it.”

5

Richard M Werner summed it up thus: “There is melody in them, and therein lies their principal merit. For they lack that weighty additional ballast that only comes with the years, namely experience of a deeper kind. The poet makes no attempt to feign such experience, he does not pretend to be older than his years.”

6

And Werner too shared the general view that the future works of this author would certainly be awaited with interest.

Some minor linguistic infelicities were noted in passing. Adelt thought that assonances such as

sinken/singt

in the lines

“die Nebel sinken—es singt der Sturm”

were probably better avoided. Tielo’s observation that the author “now and then” piles on the attributes and adjectives, citing the phrase

“glühende, brennende Küsse”

[“fiery, burning kisses”] by way of example, was not taken to heart by Zweig—for decades to come nearly every one of his publications elicited the exact same criticism. Even friends pointed out—to no effect—that he was often too free with rhetorical repetitions and emphases in his writings.

The reviewer Rudolph Strauss, finally, penned a sentence that will have done Zweig a great deal of good within the family circle: “Mr Zweig has dedicated his book in part to his parents, in part to the poet Adolph Donath. The recipients of this dedication have no reason to be ashamed.”

7

And nor were they. The proud mother Ida Zweig started a collection of newspaper cuttings with her son’s poems, essays, critical pieces and book reviews, which she conscientiously updated over the coming years.