Thyroid for Dummies (20 page)

Read Thyroid for Dummies Online

Authors: Alan L. Rubin

If the follicular tumour is over 1 cm in diameter, fixed to surrounding tissues, or starting to invade local structures, then a total thyroidectomy is recommended, especially in older people, followed with radioactive iodine therapy and long-term suppression of TSH with thyroxine hormone replacement.

Where the tumour has started to spread into local nodes, and where metastases are present, these are treated as for papillary cancer (see the previous section on treating papillary cancer).

Medullary thyroid cancer

As this type of tumour doesn’t originate in thyroid-producing cells, its treatment is a little different. A surgeon removes the entire thyroid (total thyroidectomy) as well as dissecting out all the central neck nodes, as the fact that medullary cancer does not concentrate iodine means radioactive iodine does not eliminate thyroid tissue. The person’s calcitonin level is measured at intervals to check for any regrowth of the tumour. External beam radiotherapy is sometimes used to control local recurrences, but is not used routinely as it doesn’t improve survival rates. Similarly, chemotherapy is usually unhelpful, but is sometimes used if the disease is progressive.

13_031727 ch08.qxp 9/6/06 10:44 PM Page 100

100

Part II: Treating Thyroid Problems

Family members of someone with medullary thyroid cancer have their calcitonin levels checked regularly and, if their levels are high, will undergo investigation and treatment as well. Genetic testing is also available to rule out medullary thyroid cancer in other family members (see Chapter 14 for more on genetic testing).

Undifferentiated (anaplastic)

thyroid cancer

This type of cancer is always classed as Stage IV as it’s so aggressive and spreads so easily into surrounding tissues. Surgery is usually not considered as a good option, except when needed to maintain the airway if breathing is obstructed. Radioactive iodine therapy is not used either, as these immature cells do not concentrate iodine well. For this type of thyroid cancer, external beam radiotherapy is the mainstay of treatment, with or without chemotherapy.

Following Up Cancer Treatment

Anyone who has most or all of his or her thyroid gland removed starts taking thyroid hormone replacement after surgery and needs to continue that treatment for the rest of their life. Thyroid hormone replacement simply involves taking a daily pill of thyroxine hormone (refer to Chapter 5).

Someone treated for Stage I or II thyroid cancer usually has their blood levels of thyroglobulin (check out Chapter 3) checked regularly after surgery, too. If the level starts to rise, thyroid hormone replacement is stopped for several weeks. A full body scan with radioactive iodine is then carried out, looking for any evidence of thyroid tissue. If tissue is found, the person is given a much larger treatment dose of radioactive iodine to destroy the remaining thyroid tissue. The replacement thyroid hormone is then restarted a few days later.

Stopping the thyroid hormone allows the body to produce thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), which stimulates uptake of radioactive iodine within any remaining thyroid tissue. Instead of stopping thyroid hormone replacement, your doctor can give you synthetic TSH injections for several days prior to a thyroid scan with almost as good a result.

People with Stage III or IV thyroid cancer are likely to show regrowth of their tumour at some stage. This regrowth may respond to more external beam radiotherapy or to chemotherapy using chemicals known to destroy that type of tumour cell. Unfortunately, the outlook is poor for people with recurrent Stage III or IV thyroid cancer.

14_031727 ch09.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 101

Chapter 9

Learning about

Multinodular Goitres

In This Chapter

ᮣ Knowing what causes a multinodular goitre

ᮣ Diagnosing and treating the problem

ᮣ Dealing with unexpected complications

Multinodular goitres – large thyroids with many nodules – are possibly the most common of all thyroid disorders. In various studies of people who died of other causes, between 30–60 per cent of them were found to have thyroid glands with multiple nodules. That means that up to 36 million people in the United Kingdom alone could have this disorder. What a workload for thyroid specialists! (With numbers like that, you wonder why nature placed the thyroid gland so prominently in the front of the neck near so many vital structures. Poor planning?)

Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on which side of the desk you are sitting), most people with thyroid nodules never need treatment. Only a small fraction develop the signs and symptoms discussed in this chapter and need medical evaluation.

Exploring How a Multinodular

Goitre Grows Up

Ryan (a distant cousin of our friend Kenneth from Chapter 7) is 46 years old.

He goes to his doctor for a routine physical examination, and the doctor tells him that his thyroid feels bumpy. He has no symptoms in his neck. His doctor obtains thyroid function tests, which are normal, and thyroid autoantibody 14_031727 ch09.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 102

102

Part II: Treating Thyroid Problems

tests, which are negative. He is referred to the thyroid specialist clinic. (Check out Chapter 4 for more on thyroid autoantibodies and testing.) The thyroid consultant examines Ryan and tells him that he can feel several distinct nodules, all of them soft and freely moveable. He sends Ryan for a thyroid scan, which shows that all the nodules can concentrate radioactive iodine (none of them are ‘cold’ – refer to Chapter 7). The consultant assures Ryan that he has a multinodular goitre and that no treatment is needed as long as he is free of symptoms. He asks Ryan to return in six months so that he can examine the thyroid again.

Four months later, Ryan suddenly feels pain in his neck and notices that one area has got larger. His doctor refers him back to the clinic, and the consultant inserts a needle in that area and removes a small amount of blood. He tells Ryan that a haemorrhage has occurred in one of the nodules, forming a cyst (a fluid-filled nodule) that requires no more treatment than evacuation of the blood. The pain occurs once more, and then it stops. Ryan returns every six months thereafter, and no further change takes place.

Ryan is an excellent illustration of the way that a multinodular goitre is typically discovered and evaluated and the most common outcome of the condition. Doctors believe that multinodular goitres result from some or all of the following circumstances:

ߜ Starting around puberty, sometimes related to a deficiency of iodine (see Chapter 12), the thyroid is stimulated to grow. It grows a certain amount and then enters a resting state. This growth/resting cycle is repeated many times.

ߜ The cells in the thyroid, though they almost all perform the same task of making thyroid hormone, are not identical and grow at different rates.

ߜ Certain stresses to the body, such as pregnancy, increase the need for iodine, leading to more stimulation of the thyroid.

ߜ Some foods called goitrogens (refer to Chapter 5) prevent the production of thyroid hormone and lead to more stimulation of the thyroid.

ߜ Certain drugs, such as amiodarone (taken for heart rhythm irregularities), block production of thyroid hormone, which leads to more growth of the thyroid to compensate.

ߜ A genetic connection may mean that multinodular goitres occur more often in some families than in others.

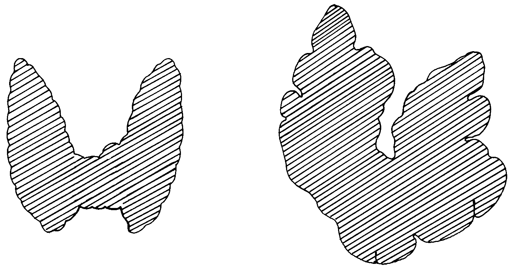

Figure 9-1 shows what a multinodular goitre looks like in comparison to a normal thyroid.

14_031727 ch09.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 103

Chapter 9: Learning about Multinodular Goitres

103

Figure 9-1:

A Multi-

nodular

goitre

compared

to a normal

thyroid.

Normal thyroid

Multinodular goiter

Ryan illustrates one way in which the goitre can be discovered, but goitres appear in many ways, including the following:

ߜ A large neck suddenly gets much larger, leading to a visit to the doctor.

ߜ Someone feels a sudden pain in his or her neck, and one side of his or her neck becomes larger because there’s bleeding in a nodule.

ߜ A doctor feels a large thyroid with many nodules during a routine examination.

ߜ Symptoms develop such as a cough, difficulty swallowing, a feeling of pressure in the neck, or a lump in the throat.

ߜ The goitre is discovered incidentally when other testing is carried out, like an ultrasound study of the neck or an X-ray of the chest.

ߜ Occasionally, particularly in older people, the person develops a heart irregularity or signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism (refer to Chapter 6 for more on hyperthyroidism).

Choosing to Treat It or Ignore It

Multinodular goitres generally proceed along the same path in most people.

When thyroid function tests are done, the results are either normal or the thyroid hormone levels are elevated, suggesting hyperthyroidism; the thyroid 14_031727 ch09.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 104

104

Part II: Treating Thyroid Problems

hormone levels are rarely low. If someone experiences sudden pain in one area of the thyroid, the thyroid specialist performs a fine needle aspiration biopsy (check out Chapter 4). Usually that area of the thyroid contains blood as a result of a haemorrhage in one of the nodules. When the blood is removed, the nodule shrinks.

If a particular nodule stands out or is harder than the others, the nodule is (Q:?biopsied) and is usually diagnosed as benign. If the nodule is cancerous, treatment for cancer is begun (refer to Chapter 8).

If the only problem is the large gland, most of the time the doctor doesn’t treat it. If the person experiences other symptoms in the neck or if the thyroid gland is particularly unsightly, treatment is usually offered.

Sometimes the thyroid, instead of growing up and out, grows downward behind the breastbone (the sternum) and is described as

substernal

. In this position, where there is little room to grow, the thyroid can squeeze other organs like the

trachea

(the air pipe from the throat to the lungs). Treatment is then necessary to reduce symptoms that arise from this condition.

Most people with a multinodular goitre don’t realise they have it, and even if they’re aware that it exists, they don’t find treating it necessary.

Making a Diagnosis

Depending upon how a multinodular goitre is discovered, a doctor can do a number of studies to determine exactly what’s going on in the thyroid gland.

A good pair of expert hands can feel the presence of many nodules (although no one can feel nodules smaller than one centimetre in size). This examination is very important because it serves as a baseline for future thyroid exams.

The doctor notes the size of the thyroid so she can compare what she feels during future examinations to determine if the thyroid is growing.

The first study of a multinodular goitre consists of thyroid function tests to see whether the thyroid is making the right amount of thyroid hormone. These test results are usually normal, but occasionally they show excess production of thyroid hormone. Thyroid autoantibody tests are sometimes requested, especially if the person has a family history of goitres. These test results are usually negative unless autoimmune thyroiditis is present (refer to Chapter 5).

If thyroid function tests indicate hyperthyroidism, the doctor looks for other signs of hyperthyroidism due to Graves’ disease. Thyroid eye and skin 14_031727 ch09.qxp 9/6/06 10:45 PM Page 105

Chapter 9: Learning about Multinodular Goitres

105

disease, described in Chapter 6, supports a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. A patient who has hyperthyroidism in a multinodular goitre has a condition called

toxic multinodular goitre

, also known as

Plummer’s disease

.

When one nodule stands out or is harder than the others, the doctor does a fine needle aspiration biopsy to rule out cancer. A thyroid scan may precede the biopsy to see whether the nodule is functional (warm or hot) or if it’s cold (refer to Chapter 7). Cancers are usually cold. However, keep in mind that the majority of cold nodules are not cancer. If cancer isn’t present, the fine needle biopsy doesn’t add any information that points to a diagnosis of the multinodular goitre.

A thyroid scan gives a general picture of the thyroid, showing the size of the gland, the many nodules, and the position of the gland, which is particularly important if it has grown down below the sternum (see the previous section,

‘Choosing to Treat It or Ignore It’).

A thyroid ultrasound test picks up very small nodules. This test is used to show whether a tender nodule is a cyst – a fluid-filled nodule – or solid.

If someone feels significant pressure in their neck or has trouble swallowing, the doctor may arrange a barium swallow: The person swallows barium, and X-rays are taken as it passes down the throat. This test may show that the thyroid gland is putting pressure on the oesophagus, the swallowing tube from the mouth to the stomach. A plain film (without barium) of the neck reveals if the trachea is deviated by the mass of the thyroid.