Ticket to Curlew

Authors: Celia Lottridge

Ticket to Curlew

Celia Barker Lottridge

GROUNDWOOD BOOKS

HOUSE OF ANANSI PRESS

TORONTO BERKELEY

Copyright © 1992 by Celia Barker Lottridge

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author's rights.

This edition published in 2013 by

Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

or c/o Publishers Group West

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Lottridge, Celia B. (Celia Barker)

Ticket to Curlew / by Celia Barker Lottridge.

Originally published: Toronto : Groundwood Books, 1992

ISBN: 978-1-55498-462-6

I. Title.

PS8573.O855T53 2007Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â jC813'.54Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â C2007-901145-4

Special thanks to the Writer in Residence Program of the Regina Public Library.

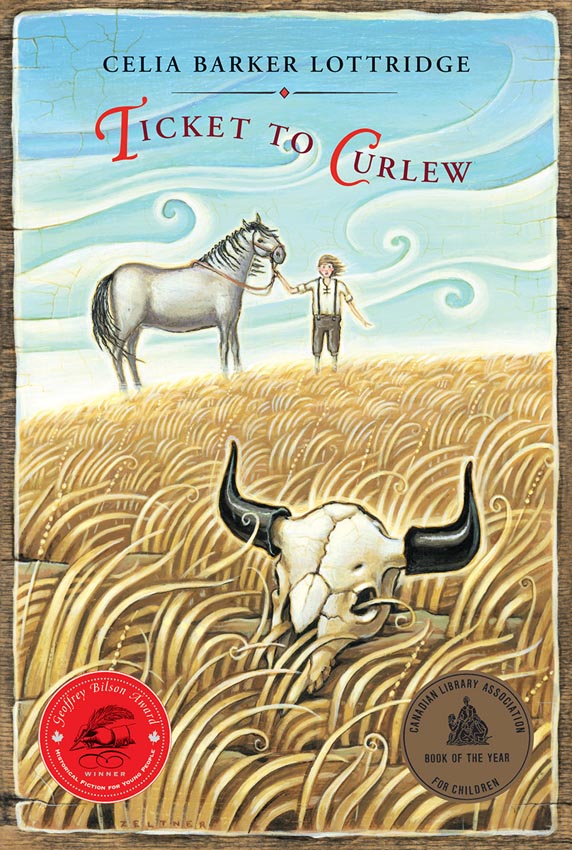

Cover illustration by Tim Zeltner

Design by Michael Solomon

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF).

For my father, Roger Garlock Barker,

who told me stories of the prairies,

and his father and mother,

Guy and Cora Barker.

THE CONDUCTOR WALKED

down the swaying aisle of the passenger car. He touched the back of each seat lightly as he moved along, looking up at the ticket stubs in the holders on the luggage rack. When he passed Sam and Pa's seat he called out, “Curlew! Next stop, Curlew, Alberta!”

Sam was on his feet in a second, reaching up for his satchel. He had been sitting in that seat for three days, ever since they had changed trains at Winnipeg.

Sam liked the train. He liked the idea that while he was just sitting there, even sleeping, he was traveling over land he had never seen before. But three days of sitting was enough.

“No need to hurry, son,” said Pa. “You know they call the stations a good ten minutes early.”

But Sam was in no mood to wait. He lugged his heavy satchel out onto the open platform at the end of the car. He had spent a lot of time out here during the journey. The air blowing across the platform always felt fresh, even when it was mixed with smoke from the engine. Sometimes the sound of the rumbling wheels and the screeching joints of the train was so loud that Sam could shout and no one heard him. If he looked down he could see the rails snaking past and watch the coupling between the cars shift.

He leaned into the corner of the railing and watched the green-gold land slide past. Since early morning the track had run along a range of low treeless hills, but now the land had ï¬attened out again.

Sam sighed. Even though Pa said the ï¬at prairie was best for farming, Sam secretly hoped Curlew would be set on the highest hill in eastern Alberta. But the track ran on as straight and level as if it had been laid out by a giant with a yard stick.

Pa came through the door carrying his satchel and the big wooden toolbox and stood beside Sam. He set the satchel down but kept a ï¬rm grip on the toolbox. It was precious. The tools had belonged to Great-grandfather Ferrier, a famous woodworker. Famous in the northwest corner of Iowa, anyway, where he had built dozens of schoolhouses and churches.

Back in Iowa Great-grandfather's tools had hung on the wall of the workshop behind the house. Each hammer, bit and ï¬le had its proper place. When the Ferriers decided to move to Canada, Pa built a box with a special space for each tool. Some of the biggest saws and the adze wouldn't ï¬t into the box. They were back in the freight car so that Pa and Sam had with them all the tools they needed to build a house for the family. Mama and Josie and Matt would come later in the summer when everything was ready for them.

The train slowed, jerked and stopped. There was a hiss of steam, and a bell rang. They had arrived at Curlew.

Sam jumped down from the train before the conductor had time to lower the steps. In front of him was a small station building just like dozens of others they had passed on the journey. Sam was not interested. He wanted to see the town. He set his satchel down beside Pa who was having a last chat with the conductor. Then he walked to the far end of the station platform and looked at Curlew.

He saw one street with small wooden buildings straggling along it. There was a church, not nearly as ï¬ne as any Great-grandfather had built. The street was dirt with deep ruts that must have been made in mud time. Along the edges boards had been laid to make a sidewalk just wide enough that two people could pass if they were careful.

At least one of the buildings was a store.

J.T. Pratt, Dry Goods and Groceries

was painted on its high ï¬at front. Beside it was a smaller building with lumber and coal stacked next to it. There was not a single tree anywhere, but some of the doorsteps had blue and yellow ï¬owers blooming beside them.

Pa joined Sam at the edge of the platform. “I guess you can see all there is of Curlew from right here,” he said.

“I guess so,” said Sam. He couldn't think of another word to say. For some reason he had been sure that Curlew would be different from all the little prairie towns he had seen from the train. Curlew would be more like Jericho, Iowa, where they had started their trip. Jericho had trees and painted houses and wide wooden sidewalks. Curlew looked as if it might disappear any minute, swept away by the prairie wind.

But Pa took a deep breath of that wind and said, “New country. That's what it is, new country. In ï¬ve years you won't know this town. People are coming from everywhere to this spot.”

Pa loved meeting new people and talking to them. It seemed to Sam that he had told everyone on the train about his plans. “My father left a good Iowa farm to my brother and me,” Pa would say. “But it just wasn't big enough to support two families. I'm the one with wanderfoot, so I was glad to sell out to my brother and buy some of this newly opened-up land in Alberta. Now we're headed for a new life. How about you?”

Then he would listen to what the other person had to say. Sam had heard a lot of stories on the train. There were other hopeful travelers who had come up from the States, drawn by advertisements for free or cheap land. Many were moving from eastern Canada because their farms were too small or their land was wearing out. Some were just looking for adventure.

None of the people they had swapped stories with had gotten off at Curlew, though.

Pa put his hand on Sam's shoulder. “We'd better stop gawking at the big city, son,” he said. “They're unloading the freight car.”

Before long Pa and Sam had gathered together all the belongings they had brought with them: the axe, saws and adze, the bundled-up tent and a few boxes of provisions. Everything else would come later with the rest of the family. Pa's farm implements, the furniture, even the cows, horses and chickens would all be loaded into a freight car to travel from Jericho to Curlew. A young man from Jericho who was eager to see the west would ride in the freight car and look after the livestock on the journey.

Now Pa looked at their small pile of belongings and said, “The Canadian Paciï¬c Railway calls our big shipment Settler's Effects. I guess we can call this batch Basic Necessities.”

Then he left Sam to stand guard over their Basic Necessities while he inquired at J.T. Pratt's store about the agent he had hired to get them a wagon and two horses and a plow. The plow they had had back in Iowa would not do the job of breaking up the tough roots of the prairie grass for the ï¬rst time.

The agent turned out to be the brother of J.T. Pratt. “How do you do, Mr. Pratt,” said Sam politely when Pa introduced him.

“Don't call me Mr. Pratt,” said the young man. “That's what they call my brother. Call me Chalkey.” He grinned and pointed to his white-blond hair. “Ask me anything you want to. I might even know the answer.”

But it seemed to Sam that Chalkey answered most questions without being asked. As Pa said later, he was a regular fountain of information. He told them all about the rainfall that spring, how promising the crops were looking, and the amazing number of people who were coming out to settle around Curlew.

“We're starting up a school,” he said to Sam. “Got to give you young people an education. It'll be close in to town here so you'll have about ï¬ve miles to travel. Your folks will want you to go, I suppose.”

“That's for sure,” said Sam, but he wondered how Josie and Matt would manage to walk ï¬ve miles to school. Josie was barely eight and Matt was six. Ten miles a day would be too much for them. It would even be a lot for him, and he would be twelve before Christmas. But Pa and Mama would think of something. They would never let their children go even a month or two without schooling.

According to Pa, a person with an education could write his own ticket in the world. After all, Pa had an education and he had written a ticket to Curlew.

BY THE TIME

all the Ferriers' goods were loaded into the new wagon it was late afternoon, too late to drive out to their land.

“Don't worry,” said Chalkey. “We don't have a hotel yet but J.T. and his wife, they'll look after you.”

Mrs. J.T., a large woman with jet black hair, welcomed them. “We're always glad to meet new settlers,” she said. “It's no trouble at all. We've set up cots in the storeroom for folks who get stranded in town. I hope you don't mind the smell of onions.” She chuckled. “The last man who slept there swore he'd get a hotel built before winter just to get away from the onions.”

“After nights of sitting up on the train, I can assure you that a cot in a storeroom sounds like luxury,” said Pa.

As for Sam, he was so glad to lie down and stretch out that he hardly noticed the smell of onions and leather boots. He just fell asleep.

In the morning Chalkey came by as Pa and Sam were ï¬nishing their pancakes and tea at the Pratts' kitchen table. He took them out and showed them the team he'd gotten for them to use until their own horses came up with the Settler's Effects. Pete was a black horse with a white blaze on his forehead, and Goldie's color matched her name.

“They're strong,” said Chalkey, “and used to prairie winters. And they are for sale if you decide you want to buy them later.” He walked over to where his own horse was tied. “I'll ride along with you and show you the boundary markers of your land. It can be a little tricky ï¬nding them even when you know where to look.”

This wouldn't be the ï¬rst time Pa had seen their piece of land. He had come up two years before, in 1913, when he heard there was good land for sale in the Canadian west. “It's the answer to our problems,” he had said when he had returned to Iowa with the deed to two quarter sections of Alberta land in his pocket. “Edward can have this farm and we'll start over. A new start in a new land.” His eyes had gleamed at the idea.

Mama had not been quite so sure. “It's a risk, James,” she had said, “and a lot of hard work. We don't know the land or the weather out there. But I'm willing to try it.”

It had taken two years to arrange everything. Now Mama was packing, Uncle Edward was getting ready to move his family into the old Iowa farmhouse, and Sam was about to get his ï¬rst look at his new home.

It didn't take long to get out of Curlew. Sam sat beside Pa on the wagon seat and looked around. It was new country, all right, he decided. There were certainly no signs of settlers: no houses, no trees, not even a plowed ï¬eld. Of course, the old farm in Iowa had miles of open ï¬elds, too. But there were elms around the house and a grove of walnut trees. Sam remembered Mama saying that Great-grandfather had planted all those trees. Maybe that land had been just as empty once.

The sun was hot on the back of Sam's neck, and the dry wind blew his hair into his eyes. Some shade would feel ï¬ne right now, he thought. So would some cool water. In Iowa there was the creek where shallow water slid over pebbles all through the summer. The creek had carved out a little valley in the black earth. It was a sheltered, private place. Sam and his cousin Zach liked to sit with their bare feet in the water on a hot day and talk.

Sam looked out over the endless rippling prairie grass. Maybe he could ï¬nd such a place out there somewhere. But it didn't seem likely.

For a long time they rode in silence. Chalkey, on his big brown horse, led the way along a faint trail in the grass. After a while he dropped back and rode beside the wagon.

“This trail runs along the section line that marks the boundary of your land,” he said. “Someday it will be a road. I guess you'll want to build your house somewhere near it.” He reined in his horse. “Look, there's one of your markers.” He pointed at a small rectangular stone half buried in the grass.

Pa said, “Whoa,” to the team. He pushed back his hat and sat with the reins slack, looking past the marker toward the horizon. “Well, Sam,” he said, “this is home and you can't beat the view. Why don't you take a look around? Find a good place to build a house.”

To Sam the place where they had stopped looked exactly like the rest of the prairie. But Chalkey and Pa knew it was the Ferriers' land. There was no use just sitting in the wagon, so Sam jumped down and began to walk north. He knew it was north because Chalkey had pointed out that all the tracks that would become roads were laid out by the compass. For the last hour they had been driving west with the sun on their backs.

But if you were away from the track, Sam didn't see how you would know one direction from another. Except for the sun, of course. Even out on this land with no landmarks, the sun would travel from east to west. That was a comfort.

Sam walked as straight north as he could for about ten minutes. Then he stopped and turned around slowly.

He was in the middle of an enormous circle. The horizon might be ten miles away or a hundred. There was nothing â not a tree, not a building, not a fence post â to give him a guide to how far his eyes were seeing. Only grass, rufï¬ed by the wind.

It was a relief to turn his eyes to the south where the wagon, the two men and the horses looked comfortingly solid and perpendicular. A relief from the ï¬atness all around.

Sam ran back to join them just in time to say goodbye to Chalkey who was mounting his horse, getting ready to ride back to Curlew.

“I expect I'll come into town tomorrow, after we see what we're missing out here. We'll need to get a well dug ï¬rst thing,” said Pa. “I'll look you up, anyway.”

Chalkey waved and went off, his horse trotting briskly as if it was glad to be going back to a more sociable place.

Pa didn't look after him. Instead he looked out across the expanse of land and nodded in a pleased way. Sam guessed he was seeing a house and a barn and plowed ï¬elds.

After a moment Pa turned back toward the wagon and said, “Now, son, we have work to do. First we should pitch the tent and organize our supplies.”

The tent they had brought was just big enough for them to lay out the two bedrolls Mama had made. Their clothes stayed in the satchels.

Pa made a lean-to shelter out of a piece of canvas and two extra tent poles. There they set up their little tin cook stove. They had brought a sack of coal to burn in it since there was no wood to be had out here. The iron skillet, the biscuit tin and their tin plates and utensils were stowed in the supply box along with the crocks of sausage, tins of tomatoes and stout bags of ï¬our, beans and dried fruit that Mama had packed. There was enough food to last them the two months until the family came, but nothing extra.

When everything was in place, Pa smiled at Sam and said, “Now that looks like home.” But it didn't, not to Sam. The tent and lean-to looked small and lonely under the huge sky. They looked too small for people to live in. Even people as small under that sky as Sam and Pa.