Tides of Light (11 page)

Authors: Gregory Benford

To Shibo he said, “Can

Argo

analyze the magnetic fields near that thing?”

Without answering, Shibo set up the problem. When she thought intensely, Shibo seldom spoke.

Toby stepped forward eagerly. “Magnetic fields! Sure, I shoulda thought. That magnetic creature, right? ’Member, back on Snowglade?

It told us then—look for the

Argo

, it said. You think it’s maybe followed us here, Dad?”

His Ling Aspect spat immediately:

This is a grave crisis you face. Do

not

let crew get out of hand or you will have even greater difficulty

.

Killeen understood Toby’s exuberance, but Ling was right: Discipline was discipline. “Midshipman, you’ll kindly remain silent.”

“Well, yessir, but—”

“What was that?”

“Uh…aye-aye, sir. But if it

is

the EM—”

“You’ll stand at attention, mister, against the wall.” Killeen saw that Besen and Loren were grinning at their mate’s dressing-down,

so he added, “All three of you—attention! Until I say otherwise.”

He turned his back on them and Shibo was at his elbow. “

Argo’

s detectors report strong fields there. Changing fast, too.”

“Um-hmm,” Killeen murmured noncommittally. He outlined to Cermo and Shibo, and the eavesdropping midshipmen, what Arthur had

conjectured. He resorted to simple pictures, describing magnetic fields as stretched bands that seized and pressed. Nothing

more was needed; explanations of science were little better than incantations. None of them had a clear notion of how magnetic

fields exerted forces on matter, the geometry of currents and potentials such a phenomenon required, or the arcane argot of

cross vector products. Magnetic fields were unseen actors in a world unfathomable to humans, much as invisible winds had driven

Snowglade’s weather and ruffled their hair.

Cermo said slowly, “But…but what’s it

for?

”

Killeen said tersely, “Keep a sharp eye.” Cap’ns did not speculate.

“Maybe caused those gray, dead zones on the planet.” Shibo pointed to the devastated polar regions, which the hoop was now

approaching.

“Um-hmm,” Killeen murmured noncommittally.

He felt instinctively that they should not fasten on one idea, but leave themselves open. If New Bishop was not a proper refuge

for them, he wanted to be damn sure of that fact before launching them on another voyage to some random target in the sky.

Now that he had a moment to recover, even this gargantuan glowing hoop had not completely

crushed his hopes that they might scratch out an existence here.

“Why’s it happening now?” Shibo mused.

“Just as we arrive?” Killeen read her thoughts. “Could be this is what the Mantis wanted us for.”

“Hope not,” Shibo said with a sardonic twist of her lips.

“We had plenty bad luck already,” Cermo said.

Shibo studied the board. “I’m getting something else, too.”

“Where?”

“Coming up from near the south pole. Fast signals.”

“What kind?”

“Like a ship.”

Killeen peered at the screen. The glorious squashed circle had cut slightly farther into the planet. It was still aligned

with its flattened face parallel to the rotation. He estimated the inner edge would not reach the planet’s axis for several

more hours at least. As it intruded farther, the hoop had to cut through more and more rock, which probably slowed its progress.

Shibo shifted the view, searching the southern polar region. A white dab of light was growing swiftly, coming toward them.

It was a dim fleck compared with the brilliant cosmic string.

“Coming toward us,” she said.

“Maybe cargo headed for the station, if they’re still carrying out business as usual.” He cut himself short; it did no good

to speculate out loud. A crew liked a stony certainty in a Cap’n; he remembered how Cap’n Fanny had let the young lieutenants

babble on with their ideas, never voicing her own and never committing herself to any of their speculations.

He turned to Cermo. “Sound general quarters. Take up positions to seize this craft wherever it comes in.”

Cermo saluted smartly and was gone. He could just as easily have hailed the squads of the Family from the control vault, but

preferred to go on foot. Killeen smiled at the man’s relishing this chance to take action; he shared it. Pirating a mech transport

was pure blithe amusement compared with impotently watching the hoop cut into the heart of their world.

The three midshipcrew left hurriedly, each taking a last glance at the screen where two mysteries of vastly different order

hung, luminous and threatening.

Killeen glided silently around the sleek craft, admiring its elegant curves and economy of purpose. Its hull was a crisp ceramo-steel

that blended seamlessly into bulging flank engines. The capture had been simple, flawless.

The squad that had seized it hovered near both large airlocks in the ship’s side. They had waited here in the station’s bay,

and done nothing more than prevent six small robo mechs from hooking up power leads and command cables to the ship’s external

sockets. Without these, the craft floated inertly in the loading bay.

It was clearly a cargo drone. Killeen was relieved and a little disappointed. They faced no threat from this ship, but they

would learn little from it, as well.

It is of ancient design. I recall the mechs using such craft when they transported materials to Snowglade. I believe I could

summon up memories of how to operate

them, including the difficulties of atmospheric reentry. They were admirably simple. People of times before mine often hijacked

them for humanity’s purposes.

Arthur’s pedantic, precise voice continued as Killeen inspected the loading bay. Arthur pointed out standard mechtech. The

Aspect was of more use here, where older, high-vacuum tech seemed to have changed little in the uncounted centuries since

humanity had been driven from space altogether. On Snowglade the mechs had adapted faster than humans could follow, making

the old Aspects nearly useless. Arthur’s growing certainty about their surroundings in this station began to stir optimism

in Killeen.

Flitters! See there?

A squad member, exploring nearby in the station, had fumbled her way through a lock. A large panel drew aside, revealing a

storehouse of sleek ships similar to the cargo drone they had just seized.

These are quick little craft that can reach the surface with ease. I remember them well. We termed them Flitters because they

move with darting ease in both atmosphere and deep space. Admirable for avoiding interception. That was before the Arcologies

lost control of their orbital factories. Before the mech grip on Snowglade grew so tight.

Killeen ordered some fresh squads to inspect the storage bay and estimate the carrying capacity of the Flitters. The Family

had explored only a fraction of the station, so it was no surprise that this storage-and-receiving bay had eluded

them. Killeen had hoped such a place might turn up; the incoming vessel had simply pointed the way.

A signal came on comm from Shibo.—Something’s happening with the hoop.—

Killeen quickly made his way through shafts and tunnels to the station’s disk surface. He had to juggle his elation at finding

shuttle ships which could take parties to the planet surface, against the unyielding fact that something vast was at work

on New Bishop.

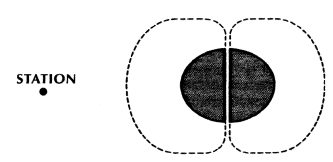

The vision that confronted him was mystifying. The hoop had nearly reached the polar axis, he saw. But it was not moving inward

now. Instead, it seemed to turn as he watched. Its inward edge, razor-sharp and now ruler-straight, was cutting around the

planet’s axis of rotation. In a simulation provided by Shibo he saw the hoop spinning about its flattened edge.

—It slowed its approach to the axis,—Shibo sent.—Then started revolving.—

“Looks like getting faster,” Killeen said.

A pause.—Yeasay…the magnetic fields are stronger now, too.—

“Look, it’s slicing around the axis.”

—Like cutting the core from an apple.—

“Revolving…”

—Yeasay. Picking up speed.—

As he watched, the hoop revolved completely around the axis of New Bishop. The golden glow brightened further as if the thing

was gaining energy.

“Pretty damn fast,” Killeen said uselessly, wrestling to see what purpose such gigantic movements could have.

The simulation grew more detailed as Shibo’s uncanny sympathy with

Argo’

s computers brought up more information.

He said quizzically, “That dashed line further out—”

—That’s this station. We’re clear of the string,—Shibo sent.

“More like a cosmic ring,” he mused.

Wedding band

, he thought.

Getting married to a planet

…“It hitting anything?”

—Naysay. Nothing’s orbiting near it.—

“Looks like somethin’ in high polar orbits.” He had picked up some of the jargon from his Aspects but still had trouble with

two-dimensional pictures like this simulation.

—That’s small stuff. Too far away to tell.—

“Much around the middle?”

—The equator? More small things. And a funny signal. Looks very large one moment, then a little later it reads as small.—

“Where?”

—Close in. Just skims above the atmosphere, looks like.—

“Sounds like mechtech. We’ve poked our hands into a beehive. Damn!”

—There’s more. I’ve been scanning New Bishop. Picking up faint signals that seem human-signified.—

“People?” Killeen felt a spurt of elemental joy. A human

presence in this strange enormity…“Great! Maybe we can still live here.”

—I can’t tell what the signals say. Might be suit comm amped way up. Like somebody talkin’ to a crowd.—

“Try getting a fix on it.”

—Yeasay, lover.—She added a playful laugh and he realized he was being too brusque and Cap’nly.

“You can get even in bed tonight.”

—That an order?—

“You can give the orders.”

—Even better.—

He laughed and turned back to the spectacle.

His mind skipped with agitated awe. It had been sheer bravado, he thought, to name this sun Abraham’s Star. A tribute to his

father, yes, and with a sudden wrenching sadness he wished desperately that he could again talk to Abraham. It seemed he had

never had enough time to learn from his father, never enough to tap that unpretentious certainty that Abraham had worn like

a second skin.

He recalled that weathered yet mirthful face, its casual broad smile and warm eyes. Abraham had known the value of simple

times, of quiet days spent doing rough work with his hands, or just strolling through the ample green fields that ringed the

Citadel.

But Abraham had not been born into a simple time, and so he had come to be a master of the canny arts humans needed. Killeen

had absorbed from him the savvy to survive when they raided mech larders, but that was not what he remembered best. The wry,

weary face, with its perpetual promise of love and help, the look that fathers gave their sons when they glimpsed a fraction

of themselves in their heirs—that had stayed with Killeen through years of blood and fear that had washed away most of the

Citadel’s soft im-

ages. He could not recall his mother nearly as well, perhaps because she had died when he was quite young.

And what would Abraham say, now that his son had named a star for him that was a caldron of vast forces, beside which humanity

was a mere fleck, a nuisance? Some promised land! Killeen grimaced.

The hoop had finished its first revolution and begun the second, hastening. Its inner edge did not lie exactly along New Bishop’s

axis but stood a tiny fraction out from it.

As Killeen watched, the cosmic ring finished its second passage, revolving with ever-gathering speed. The hoop seemed like

a part in some colossal engine, spinning to unknown purpose. It glowed with a high, prickly sheen as fresh impulses shot through

it—amber, frosted blue, burnt orange—all smearing and thinning into the rich, brimming honey gold.

—I’m picking up a whirring in the magnetic fields,—Shibo sent.

His Arthur Aspect immediately observed:

That is the inductive signal from the cosmic string’s revolution. It is acting like a coil of wire in a giant motor.

“What

for?

” Killeen demanded, his throat tight. Without ever having set foot on it, he felt that New Bishop was

his

, the Family’s, and not some plaything in a grotesquely gargantuan contraption. He called up his Grey Aspect.

I cannot…understand. Clearly it moves…to the beck…of some unseen hand…I have never heard…of mechs working on such a scale…nor

of them using a cosmic string…To be sure…strings were supposed…in human theory…to be quite rare

.

They should move…at very near the speed of light. This one must have…collided with the many stars…and clouds…slowing it. Someone

captured it…trapped with magnetic fields

.

Arthur broke in:

A truly difficult task, of course, beyond the scope of things human—but not, in principle, impossible. It merely demands the

manipulation of magnetic field gradients on a scale unknown—