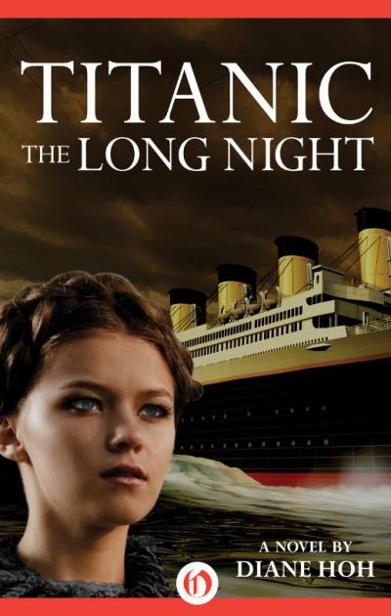

Titanic: The Long Night

Read Titanic: The Long Night Online

Authors: Diane Hoh

The Long Night

Diane Hoh

This book is dedicated to my mother

Regis Niver Eggleston,

a truly unsinkable woman.

Prologue

T

HERE WERE TWO THINGS

Elizabeth remembered most about that long, fateful night. The first was the sound of terrified cries for help. Those cries echoed in her nightmares, no matter how soundly she slept. The second was the fierce, penetrating cold. For the rest of her life, a sharp, icy wind or a sudden dive in temperature would transport her back to lifeboat number six.

It rested on the flat, black sea while its passengers, shivering and huddled together for comfort, watched the great ship

Titanic’s

lights blink and then, finally, with the bow completely submerged, go out. Even with the bright, golden lights gone, the ship, hanging nearly perpendicular in the water, its stern aloft as if pointing to the black, star-studded sky above, was still clearly visible to the survivors drifting in the open sea. They continued to watch with wide, disbelieving eyes as the liner, touted as “unsinkable,” sank, taking with it more than one thousand passengers.

It sank quietly, as if unwilling to create any more of a stir than it already had. Or, a dazed Elizabeth had thought, as if it were ashamed to be such a bitter disappointment.

And then it was gone, that most magnificent of all oceangoing vessels, gone forever.

There were so many painful memories of that night, memories that brought her sharply awake in the middle of the night, sweating and terrified. A light being turned on in a dark room reminded her of the way the ship’s lights had stayed on for so long. Hearing certain ragtime melodies brought back an image of the

Titanic’s

band, gathered at the entrance to the Grand Staircase while the lifeboats were being loaded. A late-night black sky studded with brilliant stars sent her back to the sea again.

But always, throughout her life, it was the icy, penetrating cold Elizabeth remembered most clearly about that long, terrible night.

Wednesday, April 10, 1912

During one last argument, Elizabeth Farr tried desperately to convince her parents to allow her to stay on in London with her cousins, instead of returning to New York. It was an argument she lost as always, and the Farr family left Waterloo Station at nine forty-five

A.M.

on the White Star Line boat train for Southampton. During the seventy-nine-mile journey through English villages with names like Surbiton, Woking, and Basingstoke, Elizabeth remained sullenly silent. She was still silent when they arrived at dockside shortly before eleven-thirty in the morning.

But the sullen pout left her face when she saw the great ship

Titanic

anchored in the harbor. There were other, smaller ships there, too. But the one whose maiden voyage would carry her and her parents back to New York towered over all of them. The word that sprang first into Elizabeth’s mind was “majestic.” It was enormous, its four huge funnels marching along the boat deck like giant soldiers on guard. It was the most beautiful ship she had ever seen, and she had seen several. This had not been her first trip abroad.

“Eleven stories high,” her father commented, seeing the look on Elizabeth’s face. “If you stood it on end, it would rival the tallest buildings in the world. It’s something, isn’t it?”

It was indeed something. But Elizabeth was still stinging from the morning’s argument. “If you stood it on end,” she countered crisply, “it would sink.”

For the rest of her life, whenever she remembered that remark, she would flush with anguish.

Glancing around, Elizabeth saw with satisfaction that she was not the only first-class passenger who looked excited. Others, as unaccustomed to being impressed as she was, were nevertheless staring and exclaiming, some over the sheer size of the oceangoing vessel, others over its shining beauty.

The first-class passengers walked along the gently sloping gangway to the main entrance on B deck, amidships. A man Elizabeth’s father addressed as “Chief Steward Latimer” and a purser’s clerk were there to greet them and direct or escort them to their cabins on C deck.

They passed through the entrance and walked quickly down the blue-carpeted corridors.

Elizabeth Langston Farr was used to luxury. The only child of a wealthy New York banker and his equally wealthy wife, she had never known anything else. But even she was not prepared for the impressive, lavish accommodations on board the new ship

Titanic.

Only her residual anger kept her from exclaiming with delight when confronted by the elegant foyer at the foot of the wide, curved staircase on B deck. It kept her from making any comment when she saw the large, four-poster bed in her cabin, the patterned wall-covering on the upper walls, and the rich, dark paneling on the lower walls. She pretended not to be impressed by the dainty, antique desk well supplied with fine linen stationery bearing the ship’s letterhead, or the heavy, ornate, raised molding around the doors. Angry at being treated like a child, she had made up her mind not to let one pleasant comment about this trip escape her lips. But that was more difficult than she had expected, given the beauty and luxury of the ship.

She had her own bathroom, fully equipped with thick, white towels, tiny bars of wrapped soap, and beautiful antique light fixtures. She could easily be in one of the finest hotels in Paris or London.

But she was determined not to let her pleasure show. “It’s just a ship,” she said when she moved through the doorway into her parents’ room. There was disdain in her voice. “Not a hotel. Why waste all of this on people who are probably going to be seasick, anyway?” She was referring to her mother who, although the ship was still firmly moored, was already paler than usual. “I think it’s ostentatious.”

“No one’s going to be seasick,” her father said, removing his hat. His wife was sitting on a maroon velvet chaise lounge situated at the foot of the canopied bed. “And,” he added drily, “considering what I paid for these accommodations, I would hardly expect less than ‘all of this.’ ”

“It’s such bad form to discuss money, Martin,” his wife protested, lying back against the chaise. But then she lifted her head to glance around. Their cabin was larger than Elizabeth’s. The canopied bed was further sheltered by velvet draperies hanging at all four corners, the smooth, thick bedspread a rich, embossed fabric. A finely cut crystal chandelier hung from the ceiling, the carved walnut paneling shone against the light, a brass firebox against one wall was polished to a brilliant golden shine. A delicate glass vase filled with pastel-colored fresh flowers sat on a table in the center of the room. “I must say, you can’t fault the taste. These are exquisite furnishings. As impressive as any I’ve seen in the better hotels.”

Elizabeth pulled free a pin securing the camel-hair wool hat that matched her traveling suit. She tossed the hated hat on a chair and removed the pins that held her long, pale hair in place, letting it tumble across her shoulders. “You mean the

best

hotels, Mother. When were you ever in anything less?”

“Elizabeth,” her father warned, “your mother isn’t feeling well. I’m sure she would appreciate a change in your tone of voice.”

“Well, she can’t be seasick yet,” Elizabeth replied childishly, turning to go back into her own cabin. “We’re still anchored.” And without waiting for a reprimand, she left them, closing the door after her. She didn’t slam it, though she wanted to, but the resounding click as the door shut was almost as satisfying.

Still in her suit, she flopped down on the bed on her stomach, resting her head on a soft, fat bed pillow. How could they expect her to be in good spirits during this trip, when they knew as well as she did what was awaiting her in New York? That stupid debut! An endless round of parties and dinners, in the company of shallow girls and arrogant, impeccably dressed young men who would scrutinize each of the debutantes as if they were examining a new gold wristwatch. Some of the young women would be promptly dismissed as being too plain, others because their parents weren’t important enough. Her mother would see to it that Elizabeth wore a different dress and hairdo every night. She would have to endure banal conversation, bland food, and boring company. She had no interest in any of it. But her mother was adamant, and her father, usually so supportive, had so far refused to take a stand on Elizabeth’s behalf.

The debut was bad enough. What was worse was, sometime shortly after the “season” ended, she was expected to marry Alan Reed, a wealthy banker ten years her senior. Alan was a decent sort, even if his hairline was receding and his waistcoats getting a bit tight around the middle. Though he was just twenty-seven years old, he seemed much older. He didn’t like to dance, he thought traveling was a waste of money, and in spite of having gone to the best private schools, his conversation was limited to two topics: dogs and banking. During the long hours she had spent with Alan, he had mentioned an endless amount of times that the bank his father owned was growing by leaps and bounds. He had also said, without much conviction, that he was glad he had studied banking as his father wanted him to rather than pursuing a career in veterinary medicine as he’d once thought he wanted.

Elizabeth was sure that was a lie. There was no enthusiasm in his voice when he discussed banking, none at all.

Alan was not a horrid person, but he was missing a spine.

“If you make me marry him,” she had told her parents, “I’ll kill myself!” Then, “On second thought, I won’t have to. I’ll die of boredom within six months.”

“Alan will take good care of you,” her mother had argued.

“I can take care of myself.”

“Nonsense! You’ve never taken care of yourself.”

Which, Elizabeth had to admit reluctantly, if only to herself, was true enough. But she could learn, couldn’t she? She wanted to stand on her own two feet. Not that she knew any other girls her age who did. Most of her friends would be engaged halfway through the social season, and would marry in June. “Suitable” matches, of course. Their parents always had a heavy hand in making sure all the money they spent on gowns and dinners and parties bore fruit. Pity the poor girl who came to the end of the season without a beau in tow. The only avenue left at that point was a prompt dispatch to Europe, where she might get lucky and capture a member of royalty, no matter how undistinguished the title.