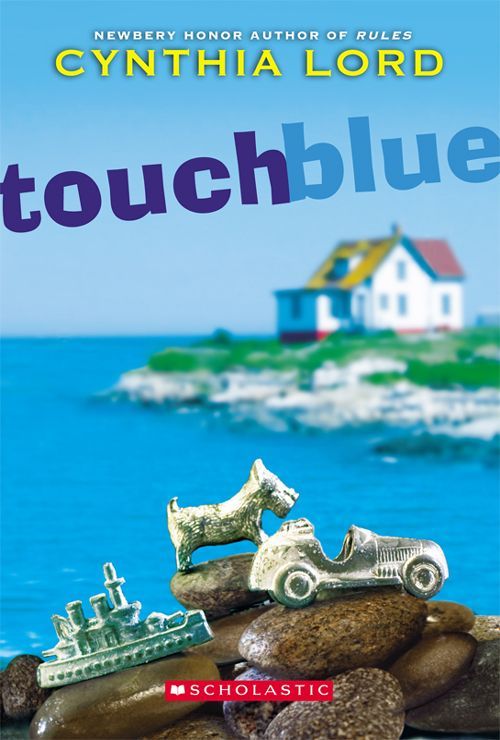

Touch Blue

Authors: Cynthia Lord

TO

MY PARENTS,

WHO TAUGHT ME

THE JOY

AND IMPORTANCE

OF FAMILY

“

T

he ferry’s coming!” High on the cliffs, my five-year-old sister, Libby, jumps foot to foot. “Come on, Tess! Mom says we can run down to meet it!”

Across the bay the ferry looks small as a toy leaving the mainland wharf. I’ve seen that boat heading for our island hundreds of times, but never with my heart pounding so hard.

He’s almost here!

“I hope Aaron likes to play Monopoly and swing at the playground,” Libby calls down to me. “Do you think he will?”

“He’s thirteen. That’s probably too old for swinging.” I know what Libby means, though. I want Aaron to like everything I do, too: reading, fishing, building things, riding bikes, and cannonballing off the ferry float into the ocean. Ever since my best friend, Amy Hamilton, and her family moved off the island last

winter, I’ve missed having someone to do those things with. When you live on a small island, you don’t get many choices of friends.

The wind quivers a brown strand of hair over my nose. My bangs are in that awful growing-out stage: too short to stay tucked behind my ears and too long to stay out of my eyes. As I wipe that hair away, I notice something sparkle near my feet among the tangles of rockweed. I reach down and pry loose a palm-sized circle of blue sea glass, just the bottom of a bottle. Once it was someone’s trash, but now the ocean has tumbled it all smooth and beautiful.

It’s extra lucky to find something blue, because there’s a saying,

Touch blue and your wish will come true.

So anything blue comes with a wish attached.

Lifting the sea glass up to my eye, I watch the whole world change: The far and near islands, the lobster boats in the bay, the summer cottages ringing the shore, even Mrs. Ellis’s tiny American and Maine flags flapping in the wind beside her wharf turn hazy, cobalt blue.

Across the water the fancy mainland houses with their big windows stare blank-eyed back at me. Funny to think we islanders are their “view.” I stick out my tongue to give them something new to look at.

Tunneling my toes under the silty clam-flat mud, I imagine Dad standing at the ferryboat’s rail, pointing out the islands to the boy beside him. I hope Dad doesn’t show Aaron everything. Aaron’s never lived on an island before, and I want to show him things, too. He’s probably never seen a seal pop his head up in the water, almost near enough to touch. Or watched a thunderstorm over the ocean, with miles and miles of lightning strikes flashing at once. And I’m extra excited to show Aaron how close it feels to flying when Dad guns the engine of our lobster boat and it skims, fast as a skipping stone, over a flat sea.

“We do our best to make a good match,” Natalie, Aaron’s caseworker, had promised me when she came out to interview us.

I’ve never met a foster child before. But I’ve read books about them. There’s Gilly in

The Great Gilly Hopkins

, Bud in

Bud, Not Buddy

, and Anne Shirley in

Anne of Green Gables

. I hope Aaron’s the most like Anne: full of stories and eager to meet us. Of course, he won’t be

exactly

like Anne, because he’s not eleven years old.

Or a girl.

Or Canadian.

“Take it slow, Tess,” Mom had said this morning over breakfast. “Remember what Natalie said? We

need to give Aaron some space. Don’t overwhelm him with questions today.”

“I won’t ask questions,” I promised. “I’ll just

tell

him things.”

Something hits my shoulder.

Up on the cliffs, Libby’s hands are full of fat, Scotch-pine cones. She scowls at me and pitches another, but it falls short. “Let’s go, Tess! We’ll miss the ferry!”

I glance to the boat crossing the bay now. “All right. I’m coming!” Running over the clam flats, my feet slap the muck. Broken mussel shells jab my feet, and my toes clench from the cold water, but I run faster with each smacking step. It might be June, but it’ll be weeks before the flats feel warm under my feet.

At the break in the cliffs, I drop the sea glass into my shorts pocket to free my hands for climbing. I know exactly where to place my feet, which rocks wiggle and which ones won’t.

“Maybe Aaron’ll like green beans!” Libby shouts down to me.

I grin up at her. “Why? So you can give him

yours

?” Stepping up to a flat ledge, I grab a little tree to steady myself. “Or maybe Aaron’ll like boats and reading, like me!”

“Or maybe Aaron’ll be able to whistle real good.” Libby blows, but only a whoosh of air comes.

“You’ve almost got it.”

Libby reaches her hands high overhead. “Or maybe he’ll be a hundred feet tall!” Her short blond hair and green plastic barrettes bob as she giggles.

Laughing with her, I clamber up the last ledge and pick up my sneakers from the grass where I’d left them. “If Aaron were that big, he wouldn’t fit in our house.”

“Or on the ferry!” Libby adds.

I look over my shoulder at the boat — closer now! Straight on, the ferry looks like a fat birthday cake from this distance, wide at the bottom, the tall wheelhouse rising like a candle in the middle.

I drop my sneakers and slide my feet into them, without even brushing the sand away.

“Hey!” Libby yells as I run past her. “Wait for me!”

But I am so full from waiting today that I can’t swallow one more drop — not even for Libby. Reaching into my pocket, I touch that lucky-blue sea glass and try to cram all my wishes about Aaron into one.

Please let this plan work.

B

y the time Libby and I reach the ferry landing, the wharf’s already crowded with tourists and islanders. I wave to Aunt Barb and Uncle Ned, but I ignore Eben Calder standing over by the rail with some summer kids. Stocky with more freckles (and less brains) than a slab of granite, Eben might be the youngest Calder, but he’s mean as any — especially toward me. Ever since kindergarten, Eben’s been a thorn in my side: always picking on me and trying to outdo me at everything.

“Do you see Aaron?” Libby presses her way up beside me.

On tiptoes, I steal a look between Reverend Beal’s arm and Mrs. Coombs’s shoulder. The ferry has pulled close enough that I can easily read the name

Island View

on the navy blue hull. I recognize some of the passengers standing in the bow and sitting on the red benches of the upper deck, but I don’t see Dad.

“Not yet,” I tell Libby. “They must be inside on the main deck.” As the crew ties up, I chew my thumbnail to keep my hands busy and listen to scraps of conversation around me:

“Of course, it’s bound to change some things….”

“… five kids in all — the same number we lost when the Hamiltons moved away.”

“… had to come up with some way to save the school, didn’t we? And the State would only give us the summer to work it out.”

I turn my head, just enough to see the Hamiltons’ old house down the shore. If wishes worked backward, I would’ve wished on that piece of lucky-blue sea glass that Amy and her family hadn’t moved off the island last winter. If they hadn’t left, the State of Maine wouldn’t be threatening to shut down our small island school, saying we don’t have enough kids to keep it open now. Plus I would still have my best friend.

If our school closes, Mom’ll lose her job as the island teacher, and many of the families living here with kids — including us — will have to move to the mainland to go to school. The mainland may not be far away in miles, but those miles change everything.

“We can’t leave here!” I told Dad. “I don’t want to

go to a new school where I don’t know anyone — where all the other kids have made their friends already!”

But he said our family needs Mom’s income and the health insurance that comes with her job. “I don’t see a way around it, Tess,” he said, spreading his hands.

Until one February night when Reverend Beal came to our house with a plan. “It’ll solve everything,” he said. “We’ll have the same number of students we had before the Hamiltons moved, and we’ll give some needy children good homes. As I see it, this could be a good thing all around. The Rosses have already said yes, and the Morrells have agreed to take

two

kids. The Webbers are thinking about it.”

Sitting at the kitchen table, I waited for Dad to say it was a crazy idea for our family to take in a foster child to help get our school numbers up again. But he just sat there, stroking his beard between his thumb and fingers.

“The older children are harder to place, and the caseworker seemed very pleased that we might be willing to take a teenager, as well as the younger ones,” Reverend Beal continued. “If we get going now, we might have this all settled by summer, well before school starts in the fall.”

I held my breath and let myself imagine it: Mom not worried about her job anymore and Dad not talking about selling our house, and me staying right here with everything I know and love. I’m sure Mom and Dad would take great care of that kid, too. So maybe it could be a good thing all around?

“I don’t know,” Dad said. “It doesn’t seem completely

right

.”

“We have a strong, loving home.” Mom’s index finger circled the top of her coffee mug, the way it does when she’s trying to talk Dad into something. “How can it be wrong to share that with a child who needs one — even if he brings us something in return?”

Dad couldn’t answer that, so today a thirteen-year-old boy is moving into our attic.

Libby’s just learning to add, so I explained Aaron’s life mathematically to her by drawing it in the wet sand with a stick one day:

5 + 6 + 1 + 1 = 13

Aaron had lived with his mother until he was five years old. Then some people from the State took him away, because they thought his mom wasn’t doing a good enough job of taking care of him. Next he’d lived with his grandma for six years, until she died.

And after that, he’d lived one year each in two foster homes.

“Why didn’t he go back to his mom when his grandma died?” Libby asked.

“He couldn’t.” I took a deep breath, wondering how to explain the situation in words she’d understand. “No one knew where Aaron’s mom was when his grandma died. She didn’t show up to the meetings she was supposed to go to, and now Aaron doesn’t belong to her anymore. A judge said so.”

“Could a judge say that about

me

?” Libby asked, her eyes wide.

“No. Don’t worry,” I told her. “We’re fine. But Aaron needs a new family now, and that’s gonna be us.”

As the ferry crew slides the ramp into position, I wonder what Aaron’s thinking. Is he scared, hoping we’ll like him? I practice my biggest smile, so he’ll feel welcome immediately.

“Hey, Tess!” a familiar voice says.

I tip my chin up to use all my height. Even though I’m eleven years old and Jenna Ross is only ten, I always feel short and plain standing next to her. Jenna’s already half a head taller than me, and she has golden curls, like the angel in the stained-glass win

dow at church. My hair’s pitch brown and straight as pine needles.

I suspect Jenna would like to be my best friend now that Amy is gone, but it feels doubly wrong. Not only because Jenna can’t ever replace Amy, but also because Amy never liked Jenna. She said Jenna was stuck-up over being pretty.

“I hope the new kids are nice,” Jenna says. “Especially Aaron and Grace.”

The other island foster families wanted kids close to Libby’s age, but I’m happy we’re getting an older one. Aaron’ll be able to do more things with me. And I think it’ll be fun to be a little sister for a change, instead of always being the responsible older kid.

“I baked Grace a cake to celebrate her first day with us,” Jenna says. “I hope she likes chocolate.”

Why didn’t I think of that? I should’ve made Aaron something.

“Does Aaron have to go to meetings with his real parents?” Jenna whispers. “We’ll have to take Grace to the mainland every Tuesday, because her mom’s trying to get her back eventually.”

I shake my head. “Aaron doesn’t belong to his mother anymore — not legally, anyway.”

“I wish it were like that for us. It feels like we only get to borrow Grace.” Jenna sighs. “We even have to get permission for her to have a haircut.”

“Why can’t

Grace

decide?” I ask. “It’s her hair.”

Before Jenna can answer, someone shouts, “Here they come!” and we both jump to our tiptoes.

“Can you see Aaron

now

?” Libby steps on my foot to make herself taller.

“Ouch! Get off me, Lib.” My eyes skim the line of passengers hurrying off the main deck. A tourist wearing a huge backpack steps gingerly from the ferry ramp to the wooden float, holding up the line behind her.

“Go!” I whisper, wanting her out of the way.

I see Mr. Webber bend down to tie a little boy’s sneaker. Beside them, Mrs. Ross smiles, patting the long blond hair of a little girl clutching a stuffed panda and a picture book.

“That’s Grace!” Jenna weaves a path through the crowd.

On the metal gangplank, the passengers’ footsteps boom like a thunderstorm. A wet breeze off the water raises goose bumps on my skin, and I rub my arms to warm them. The air smells, a mix of salt water, bait, pine trees, wet wood, and diesel fuel.

A few tourists grab the rail as the ramp rolls back and forth with each ocean wave. Behind them, some islanders pull coolers on wheels and carry extra-large tote bags crammed full of groceries. Glancing back to the ferry, I spy Dad’s Red Sox cap in the line of passengers. “There they are!” I wave, but Dad’s speaking to the ferry crew, who are unloading boxes, groceries, and bags of mail.

Then I see Aaron. Skinny as a spar, he seems too tall for thirteen, with a pinched-sour mouth and red hair. A redhead on a boat is unlucky! Why didn’t I remember to mention

that

to his caseworker? His hair, bright as October leaves, falls near to his shoulders.

“Does he look like someone who’ll love swinging?” Libby asks, straining to see.

People push around me, but I can’t move. I don’t know what I was expecting, but I wasn’t expecting Aaron to be

this

boy. He looks weak, with skin so white it seems almost unreal. He’ll burn to a crisp out fishing with us.

He can’t help those things, but still —

In front of me, Mrs. Coombs tsks her tongue. “That redheaded one’s a juvenile delinquent if ever I saw one.”

“Now, Shirley.” Reverend Beal starts in preaching about Jesus, but I can only stare at the boy climbing

the gangplank. Aaron never once touches the rail — just clutches a black musical instrument case in one hand and keeps the other pushed deep into a pocket of his leather jacket.

“This is Libby and Tess.” Dad holds an old tan suitcase in one hand. “We’re all glad you’re here, Aaron. Isn’t that right, girls?”

“Yes!” Libby shoves by me and throws her arms around Aaron’s waist.

Aaron lifts one hand cautiously. He gives Libby a little, quick pat on her back and then steps away from her.

I push my lips into my widest, welcomest smile. “Hi, Aaron!”

He glances at me. His eyes are muddy green, like the sea deep in the coves. “Hi.” He says it flatly, like I’m just anybody.

Why’d Natalie pick this boy for us? A fear whispers in me that maybe she didn’t have anywhere else to send him.

Walking down the wharf, I hear Dad stumble a few words about the island and how living here might take some getting used to, but it’s a good place.

We pass the ferry landing parking lot full of old or second-best island vehicles: station wagons with

1970s wood paneling, golf carts, motorcycles, motorized scooters, and every kind of beat-up truck you can name.

“When you live on an island, you need two cars,” Dad explains. “The newer one stays on the mainland, and the older one comes to the island — to die.” He gives a joking smile.

But when Dad looks away, Aaron rolls his eyes.

I reach into my pocket to touch that blue sea glass. Maybe I should’ve been more specific with my wish?