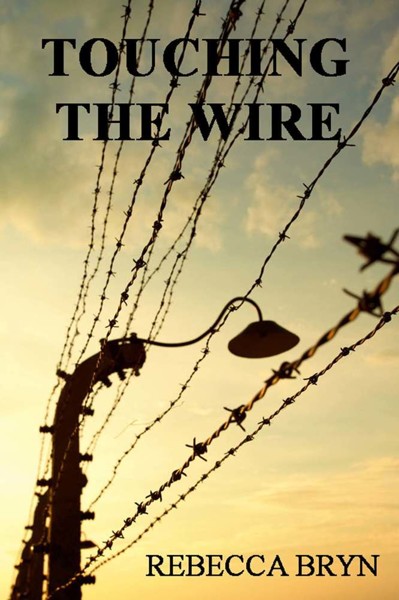

Touching the Wire

Authors: Rebecca Bryn

Tags: #Mystery, #Historical, #Thriller, #Suspense

TOUCHING THE WIRE

BY

REBECCA BRYN

Text copyright © 2014 Rebecca Bryn

All rights reserved

Although based on the

testimonies of holocaust survivors, apart from the known Nazi war-criminals

mentioned and the four brave women who were executed for being members of the

resistance, all the characters in Touching the Wire are fictitious and any

similarity with real people is purely coincidental.

With

grateful thanks to Sarah Stuart, author of Dangerous Liaisons, for her

unstinting support, time and friendship, to my long-suffering husband for his

patience, to Robert Sayer for answering legal questions, to Frances for

reading, cooking and furries-therapy, to those survivors courageous enough to

share their experiences with the world, and to Walt and Miriam for showing me

how lucky I am and how much I owe those who fought for my freedom

.

Dedicated to the memory of the real Dr Schaeler, and all

those who have suffered the hand of tyranny.

All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that

good

men

do nothing

.

Edmund Burke 1729-1797

ONE

In the Shadow of the Wolf

Walt slid his chisel into its slot at the back

of his bench and sipped the tea he’d let go cold. He eased a sepia photograph

from his wallet. For thirty-four years he’d carried Miriam’s likeness, faded

and tattered around the edges: she’d left footprints in his heart, trodden deep

and clear. Her voice echoed and his heartbeat quickened. The tramp of feet,

marching from the spring of 1944, jarred the brick floor beneath him into

hard-packed grey earth. Left, right, left, right…

He marched with them: dust

scoured his eyes and throat, and gritted the sweat on his back. The kommando of

haeftling, striped berets and coats creating an army of Colorado beetles, kept

time with the SS guards. Despair choreographed their puppet-like movements:

heads pushed forward, arms straight down, wasted faces devoid of expression.

Behind them, ambulances rattled to a stop.

The sound of boots and clogs

faded beneath the hiss of steam and the clatter of couplings as the rumble of

iron on iron ground to a halt. The line of cattle wagons, each bearing the

insignia of their country of origin, and some with a roughly-painted yellow

star, snaked into Stygian distance.

Smoke and steam mingled with

the sickly-sweet pall that hung over the camp day and night. Flakes of ash from

the chimneys danced with smuts of smoke, and floated to the ground with the

grace of angels. Already the day was hot. Inside the wagons it would be

suffocating.

‘Öffnen die Wagen!’

Wagon doors rolled back with

squeals and grinding crashes, drowning the swing tune belted out by the camp

orchestra. Eyes stark with bewilderment blinked against the light.

‘Aussteigen.’ An SS officer

waved his pistol. ‘Schnell! Schnell!’

Men tumbled onto the ramp.

Women clutched babies to their breasts and gathered children to their skirts,

their eyes searching the faces around them.

A woman cupped her hands in

supplication. ‘Vis.’ A yellow star emblazoned her coat. Hungarian. Jewish.

They’d been arriving by the wagon-load. ‘Viz…

kérem

.’

The words for water, bread

and help were burned into his memory in every European language. The woman

begged for water. He could offer no drop of water, no morsel of bread or shred

of hope.

‘Viz. Wasser…

Bitte

.’

A stooped, grey-bearded figure held up four fingers. The journey from Hungary

had taken four days: four days without food or water.

The crowd swelled across the

ramp as the wagons vomited more souls than they could possibly contain,

bringing with them the stench of excrement. A guard hustled the men and older

boys from the women and children, forming them into two ragged lines along the

tracks.

A detachment of haeftling

quick-stepped forward and heaved bodies from the wagons, laying them in rows

upon the aching ground. The old, the little children: their bodies weren’t

heavy even for those barely fleshed themselves.

A young woman bent to

retrieve her possessions. An SS officer strode past. ‘Leave. Luggage

afterwards.’

She stood, wide-eyed like a

startled deer, one arm cradling a baby. Beside her an elderly woman clutched a

battered suitcase. The girl’s eyes darted from soldier to painted signboard and

back. ‘What are we doing here, Grandmother? Why have they brought us

here

?’

The wind teased at her cheerful red shawl, revealing and lifting long black

hair. She straightened and attempted a smile. ‘It’ll be all right, Grandmother.

God has protected us on our journey.’

‘Where’s your Father?’ The

old lady adjusted her shawl, covering shock-white hair. ‘Miriam, I can’t see my

Jani.’

‘Father will be helping Efah

and Mother with the children.’

‘And where are our precious

things…’

‘They’re here, Grandmother.’

Voices rasped, whips cracked,

dogs barked. The men and boys were marched away, craning necks for a glimpse of

wives, mothers, sisters and children. At a signal, the remaining haeftling

broke ranks and began searching wagons, and carrying bundles and suitcases to

waiting

lorries

. Miriam’s grandmother’s case fell

open: a beetle snapped it shut and scurried it away. Something had fallen out:

in the bustle no-one saw him pick up the small wallet and tuck it inside his

shirt.

More orders followed: more

cracking whips and snarling dogs. The line of women and children stumbled

forward across the railway sleepers, leaving behind tumbled heaps of abandoned

lives.

The march through the camp

took forever, yet it was over too soon. At the junction, guards ordered the

women to halt. Smoke from the chimneys obliterated the sky: a wind from the

west blew the stench of it across their path.

‘Zwillinge, heraus!’

He,

the hated Hauptsturmführer,

stood before them dark hair smoothed

back, his Iron Cross worn with casual pride. His eyes pierced the crowd; his

gloved hand held a cane with which he pointed bewildered women to the left or

the right.

He shuddered, knowing what

the man sought.

An SS officer pushed towards

a woman of about fifty. ‘How old?’ She didn’t respond so the officer shouted the

question.

He edged closer. As a doctor

he held a privileged position, but he’d also discovered a gift for languages.

He translated the German to stilted Hungarian, adding quietly, ‘Say you’re

under forty-five. Say you are well. Stand here with the younger women.’ He

moved from woman to woman, intercepting those he could. ‘Say you are well. Tell

them your daughter’s sixteen. Say she’s well. Say you can work or have a skill.

Tell them you’re not pregnant.’

The Hauptsturmführer waved

his cane. ‘You, to the right. No, the children to the left.’

A woman clutched her

children’s hands. ‘I can’t leave my babies.’

He froze, fearing for them

all. The thunder of another train grew closer and the SS officer gestured her

to the left with her children. He breathed again, ashamed at feeling relief,

and hurried to intercept the next group.

The girl with the red shawl

was there, in front of him: the old lady had called her Miriam. He touched her

arm. ‘Say you’re well, Miriam. Say you can work. Give the baby to your grandmother.

She must stand to the left with the children. You must stand to the right.’

‘My grandmother isn’t well.

I’m a nurse. I can look after her and Mary.’

A guard strode past.

‘Together afterwards.’

He nodded, compounding the

conspiracy of silence. ‘Together afterwards.’

The old lady held out her

arms for the baby. ‘Go, Miriam. God be with you.’

Miriam’s eyes glistened.

‘May He rescue us from the hand of every

foe.

’ She

touched her grandmother’s cheek, a gentle, lingering movement, and placed a

tender kiss on her baby’s forehead.

She moved where he pointed

to stand with a group of about thirty young women: only thirty? Her eyes

followed her grandmother and daughter as they were swallowed into the thousands

that straggled towards the anonymous buildings beneath the smoke. Ambulances

passed, carrying those who couldn’t walk; a truck bearing a red cross followed

behind. She watched until they disappeared from sight and then searched the

faces of the women that remained.

Miriam’s eyes met his. He

had no way to tell her he had given her life: no right to tell her to abandon

hope.

Holy Mary, mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and in the hour of

our death.

***

The doorknob rattled, jolting Walt back to the

workshop at the end of the garden: Kettering, England, 1978. He slipped the

photograph away and covered his work, heart thudding. He turned the doorknob.

‘Charlotte… Did you want me, little one?’

‘You promised us a story,

Grandpa.’

He shooed Charlotte outside

ahead of him and turned the key in the lock. He clipped the key to a chain,

alongside a smaller brass one, and put both keys in his pocket.

‘Grandpa…’ Charlotte plucked

his sleeve.

Lucy, her mirror-image,

mimicked Granny’s best exasperated sigh. ‘The little girls, Grandpa. Tell us

about the little girls.’

Machines, clattering from

open windows in the shoe-factory behind the workshop, settled into a rhythm

steadier than his heart. He ruffled Charlotte’s blonde curls absently and sank

into his deckchair, already standing outside the snow-wrapped building, many

miles and years from the garden of the back-street terrace. A wolf stalked the

edges of his mind and long-dead faces pleaded for help he couldn’t give.

‘A woodcutter lived deep in

the forests of Günsburg with his wife and two little girls, and some chickens.

They were happy and free, except for the wolf.’

Blue eyes widened. ‘A

wolf?’

He nodded. ‘The woodcutter

was afraid to let his daughters into the forest alone so he decided to slay the

wolf. He put on his green jacket, and his hat with a feather, and went outside

to kill a chicken.’

Charlotte sobered. ‘Why?’

‘His daughters’ lives were

more important to him than the

chicken’s

. He put

poison inside the chicken and set off to find the wolf’s lair. He dropped the

chicken onto the ground and climbed a tree to watch.’ He pushed away memories

of electrified barbed-wire, hunger, thirst and relentless cold. ‘The wolf crept

from his lair.

Sniff, sniff,

sniff

.

I smell

chicken

… He dragged the chicken inside.’

Charlotte tilted her head to

one side. ‘Did the wolf die, Grandpa?’

He brushed a stray curl from

her face. ‘The woodcutter thought he was dead but he was only sleeping a long,

long sleep.’

Lucy screwed up her face.

‘So he might still eat the little girls?’

He sought for a prettier

tale to distract her, but he’d been only three when the mud of The Somme had

sucked the life from his father and his mother’s struggle to raise him alone

hadn’t included fairytales.

Charlotte slashed at an

imaginary foe. ‘Grandpa won’t let the wolf eat us, Lucy. Grandpa will kill him,

dead, like this.’

She had the courage he’d

lacked. Would it have made a difference? ‘It’s not good to kill, Charlotte.

No-one has the right to take another’s life.’

‘But if he’s going to eat me…’

Why had he got into a moral

debate with five year-olds? They always found holes in his logic big enough to

fall through.

Lucy picked at a scab.

‘Granny says eating people is a sin.’

‘She did?’

‘She says it’s a comment

from God.’

‘A commandment. People

believe different things, Lucy. A long time ago people believed in lots of

gods.’

‘When we were little?’

‘Longer ago than that…

long before even I was born.’ Charlotte’s mouth made a circle round enough to fit

a whole plum. He smiled. ‘They thought the sun was a god, and the moon was a

goddess.’ It made more sense than the Catholic dogma he’d absorbed from his

mother.

Pray for us sinners, now and in the hour of our death…

Her plea

had struck terror into his young heart.

Take me from the dark. Hear me now, O Lord.

Her God hadn’t heard

him in his darkest hours; He hadn’t heard her when the aerial bombardment razed

her home to the ground, burying her and his sister, when the Second World War

was all but over.

Jane arrived with drinks and

biscuits, and drove both wolf and God from the twins’ minds with an ease he

envied.

‘I’ll take my tea in the

workshop, love… do a bit more to Dobbin. Come and see what you think.’ He

opened the door, making dust motes dance in the beam of sunlight. The rocking

horse stood on the brick floor waiting for a coat of primer: it was a present

for the twins’ fifth birthday. Arturas and Peti had been five.

Jane put the mug on the

bench among shapes hidden beneath dustsheets. ‘The twins will love him.’

Dimples chased the wrinkles from the corners of her mouth. ‘Don’t let your tea

go cold again.’

His gaze lingered on his

wife’s plump form as she retreated down the path towards the kitchen, measuring

the too-rapid drip of time they had left together. He breathed in the scents of

roses, lavender and leather before locking the door and removing the shroud

from his other, secret, more pressing

task.

He brushed back a strand of

grey hair. He took no pleasure from the work for each stroke of mallet on

chisel laid his soul bare. With a surgeon’s precision, he gouged his nightmares

into the tortured shapes, sanded truth into each curve, and wrote in them his

guilt.

Five carvings. Four were

living flames in burr elm. The fifth, carved from straighter-grained lime-wood,

depicted a wolf leaping through flames. Two short burr-elm cylinders, shaped

like lighted candles, echoed the theme of fire and completed the work. Thoughts

of mortality had made him take up his chisels, but he was desperately afraid of

what would happen if he re-awakened the wolf too soon.