Trailer Trashed: My Dubious Efforts Toward Upward Mobility (2 page)

Read Trailer Trashed: My Dubious Efforts Toward Upward Mobility Online

Authors: Hollis Gillespie

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Professionals & Academics, #Journalists, #Humor & Entertainment, #Humor, #Essays, #Satire

The stories in this book are true so long as the truth can be trusted

to my recollection (barring hyperbole and hallucination). Also, some

names have been changed and events reordered. In fact, seeing as how

certain memoirists are getting their asses ripped in half for fabricating

elements in their books, I feel it's important that I finally come clean

about a few things:

First-and please forgive me for this, because I know how important this is to my image-I was never actually, not in the literal sense,

anyway (or any sense for that matter), a teenage prostitute to the stars.

There, I said it.

But once Rod Stewart hit on me when I was 15. That's true.

Okay, what really happened is that he hit on my friend, or someone

who could have been my friend if I had, like, known her. Probably.

And Lary might not be running a meth lab out of his house after all,

per se. I'm not committing. And I sincerely regret anything I said that

could have misled my readers into believing Lary is insane, including

my frequent assertions that Lary is insane.

van,d, 911,&,L

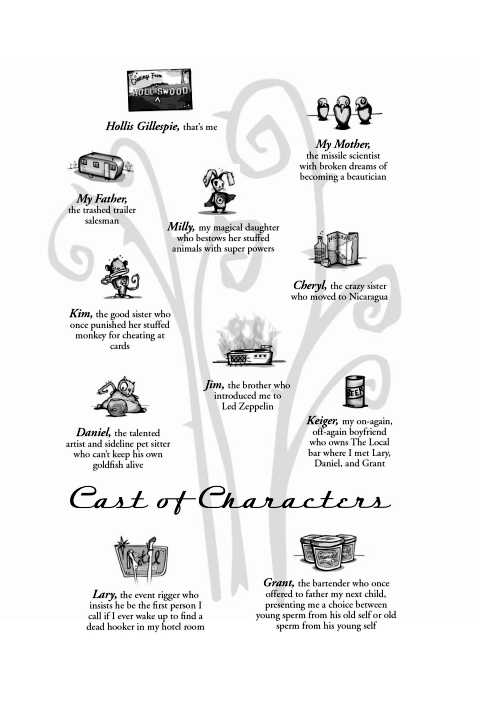

The following are stories that recall my late father, a trashed trailer salesman who liked to bake cakes, and my late mother, the reluctant missile

scientist he married, as well as the hard fighting childhood they forged for

me along with my siblings, Kim, Cheryl, and Jim. We would eventually

scatter throughout the globe, and I, the true daughter of a traveling salesman, would become a career traveler, first for a failing airline and then

stumbling to find my way without a corporate safety net.

On the journey with me are my three best friends, Lary, Daniel, and

Grant, not to mention Keiger, the owner of the bar where we all met,•

and my daughter Milly, "the happy accident. " I started collecting trailers

because they reminded me of good family times. In the trailer homes of

my childhood, for example, my father got to be proficient, my mother got

to be impressed with him, and my sisters and I, at least for as long as the

hookups were connected, got to buy the whole blissful picture.

THE FIRST TIME I FLEW, I WAS SEVEN and sick with a bad cold. Knowing now what I know about cabin pressure, I'm surprised my little head

didn't explode like a frog with a firecracker up its ass and splatter the

entire cabin with snot. It certainly felt like it would. Our mother, who

was a little useless at conventional mothering, was commonly at a loss

when her kids were sick. The most we could hope for was a show of

odd courtesies-such as the time my sister got to choose the cartoons

we could watch after she came home from the hospital after shoving a

button so far up her nose it almost reached her brain-and this time,

when being sick somehow afforded me special seating priority.

"Hollis is sick," my mother reminded my sisters, "let her sit by

the window."

The flight lasted five hundred years, or at least it seemed that

way. We were leaving to live in Florida, where my mother had scored

work designing rockets for NASA. Until then, most of our nomadic

lives had been confined to the state of California, which is luckily a

very large state. In my seven years we had moved nine times, from

northern to southern California, but nowhere in between, just lots of

different places jumbled at either extreme.

Before our mother landed this new contract, we had been living in a somewhat dilapidated apartment project in Costa Mesa, and

before that we had lived in a minor mansion on 17 Mile Drive in

Monterey. As a contract worker building missiles and rockets for the

government, my mother's income would ebb and flow in accordance with each administration. Either there would be a huge demand for

bombs and rockets or hardly any at all, with our lifestyles inevitably

reflecting either extreme and nowhere in between.

Right before we packed up to move to Florida, our father had

been selling Silver Streak trailers at a big convention down at the fairgrounds. The Silver Streak brand was created as the affordable alternative to Airstream, though we couldn't afford one ourselves. Our

mother was between contracts, and she helped decorate the different

types of trailers. There were four, so she chose the four seasons as a

theme. I remember the fall-seasoned trailer the best because she had

sprinkled the small kitchen table with dead leaves.

Even at seven I questioned the aesthetic of dead leaves, but it was

a motif that would stay with my mother for the rest of her life. Years

later she decided to "go tropical" with our living-room interior by festooning the walls with giant palm fronds and circling bamboo place

mats around a centerpiece that turned out to be a large ornate opium

pipe she'd picked up at Pier One. This happened after we'd moved yet

again, this time back to California, because when it came to locales it

was always the East or the West, one coast or the other, and nowhere

in between.

In the fall-seasoned show trailer, the kitchen table converted into

a double bed after you dismantled it, dropped it down, positioned it

to fill the space between the booths flanking either side, and evened

it out by adding the cushions that formerly made up the backrests.

In the end you had a bed as comfortable as a bag of Brillo pads, but

our mother seemed to think this feature was amazing. Somehow the trailer slept six, though nearly all the sleeping areas required similar

convoluted conversions before you could actually sleep in them.

"Really, it's simple," our mother would say as conversationally as

possible to any passers through, "you just pull this out, push this up,

and anchor it here. Isn't that amazing?"

Turns out what's simple for a missile scientist isn't necessarily so

for anyone else, which might be one reason the poor man's answer

to Airstream faded into oblivion with hardly a blip in the history of

trailer consumerism. But until then our mother was trying like hell to

help my father sell one.

On the trailer's kitchen table, in the middle of the leaves, she

placed two carved decoy ducks. Our father's company folded soon

after the convention, and none of the decorative accents our mother

had personally provided the four show trailers were returned to her.

Of considerable value, she complained, were the decoy ducks in the

fall-themed trailer. She still lamented their loss even as she sat next to

me on the plane ride to Florida, where she was due to start her new

job and we our new lives. Again.

It made me remember our mother marveling at the many inward

conversions the trailer was capable of in order to sleep six. We were a

family of six, she joked. We could all live there. "Really, it's so simple,"

she'd say to customers, who scurried away like pampered cats avoiding a lonely visitor. They could sense her hope, I realize now, that if

her husband could just sell a trailer, then maybe she wouldn't have to

convert inwardly again in order to sleep a family of six.

GROWING UP, I DON'T THINK I CAN REMEMBER a day I walked in the door

of our house without being greeted with an outburst of some kindand ducking. Ducking was essential, because you never knew what you

were gonna get hit with. Once I got hit in the face with a wooden spoon

covered in brownie batter, which my big sister, Cheryl, had hurled at me

from across the kitchen (at that moment, she'd remembered that five years

earlier I'd thwacked her in the head with a tennis shoe while she talked on

the phone, which I'd done because, a year before that, she'd thrown a lamp

made of deer antlers at me while we were visiting my uncle the hunter). So,

both figuratively and literally, stuff was always swirling around our home.

But at least yelling preceded it, so we wouldn't be caught unprepared.