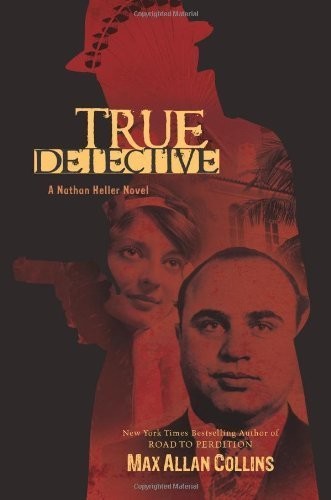

True Detective

Authors: Max Allan Collins

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Mystery & Detective

True Detective

MAX ALLAN COLLINS has earned an unprecedented seven Private Eye Writers of America "Shamus" nominations for his "Nathan Heller" historical thrillers, winning twice

(True Detective

, 1983, and

Stolen Away

, 1991). Termed "mystery's Renaissance Man" (by Ed Hoch in

The Best Mystery and Suspense Stories of 1993)

, Collins has created three celebrated contemporary suspense series: Nolan. Quarry and Mallory (thief, hitman, and mystery writer respectively). He has also written four widely praised historical thrillers about real-life "Untouchable" Eliot Ness, and is an accomplished writer of short fiction: "Louise," his contribution to the popular anthology

Deadly Allies

, was a Mystery Writers of America "Edgar" nominee for best short story of 1992. He scripted the internationally syndicated comic strip

Dick Tracy

from 1977 to 1993, and wrote three

Tracy

novels. Working as an independent filmmaker in his native Iowa, he wrote, directed and executive-produced

Mommy

, a suspense film starring Patty- McCormack, which aired on Lifetime cable in 1996; he performed the same duties for a sequel,

Mommy's Day

, released in 1997. The recipient of two Iowa Motion Picture Awards for screenwriting, he wrote

The Expert

, a 1995 HBO World Premiere film starring James Brolin. A longtime rock musician, he has in recent years recorded and performed with two bands: Seduction of the Innocent in California, and Crusin in his native Muscatine, Iowa, where Collins lives with his wife, writer Barbara Collins, and their son, Nathan.

MYSTERIES

Published by ibooks, inc.:

NATHAN HELLER MYSTERIES

by Max Allan Collins

True Detective

True Crime

(coming June 2003)

The Million-Dollar Wound

(coming August 2003)

AMOS WALKER MYSTERIES

by Loren D. Estleman

Motor City Blue

•

Angel Eyes

The Midnight Man

•

The Glass Highway

Sugartown

•

Every Brilliant Eye

Lady Yesterday * Downriver

TOBY PETERS MYSTERIES

by Stuart M. Kaminsky

Murder on the Yellow Brick Road

He Done Her Wrong * Never Cross a Vampire

The De'ti! Met a Lady

THE LAWRENCE BLOCK COLLECTION

After the First Death You Could Call It Murder

•

Deadly Honeymoon

Alfred Hitchcock in The Vertigo Murders

by J. Madison Davis

The Big Heat

by William P. McGivern

To Barb with love

A

Publication of ibooks, inc.

Copyright © 1983,2003 Max Allan Collins

Introduction copyright © 2002 Max Allan Collins

An ibooks, inc. Book

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

ibooks. inc.

West 25

th

Street

New York NY

ISBN 1-58824-761-

Cover photograph copyright

©

Brian Leng / CORBIS

A LIGHTBULB MOMENT

An Introduction to

True Detective

For the first few years of my writing career, I taught part-time at a community college. One of the ways I kept my sanity was by teaching a course on mystery fiction. It was in my capacity as a college instructor, then, that I re-read my favorite mystery novel, Dashiell Hammett's

The Maltese Falcon

, for the umpteenth time.

Perhaps it was that academic mode of thought that made me glance at the indicia page, note the copyright, and muse, "Nineteen twenty-nine… that's the St. Valentine's Day Massacre. That means Sam Spade and Al Capone were contemporaries."

In the comics field (where I also occasionally toil), this moment might be marked by a lightbulb going on in a balloon over my head. It was that kind of idea- the stray thought that lights up the world and changes everything, or at least a career.

For a long time I had been looking for a way to write private eye novels in the classic mode. I grew up on Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Mickey Spillane and dozens of their imitators, but my first published novels did not include the private detective narrator those writers made famous. Instead, at the University of Iowa's Writers Workshop, I wrote a trio of novels about three different protagonists: a thief, a hitman and a mystery writer; but in each case, the novels had roots in the P.I. form as much as the crime novel.

My lightbulb moment probably took place around 1974, not long before

Chinatown

came along, doing something of the same kind of P.I.-in-history thing I had in mind. And a couple of mystery writers, good ones (Andrew Bergman and Stuart Kaminsky), did their own period private-eye novels right around the same time.

Robert Towne's great screenplay for

Chinatown

loosely dealt with historical events, but his characters were fictional. Both Bergman and Kaminsky placed their P.I.s amid real people- chiefly, movie stars and various other Hollywood celebrities- but not in the context of actual events or specific crimes.

My concern, back at the end of the '60s and start of the '70s, was that the private eye character had become anachronistic- I did not (and still do not) care for the Marlowe type of noble-urban-knight detective earned over bodily into modern times (those times starting around 1963), a guy in fedora and trenchcoat with a bottle of whiskey in his bottom desk drawer, who apparently stumbled into a time machine.

Such novels seemed to me forced, cliched, ungainly pastiches of a form that was fixed in the amber of a bygone day. That was why my lightbulb epiphany was so crucial to me: I had come up with a way to write the private eye today… by setting the stories yesterday.

The first incarnation of the Nathan Heller character (the protagonist of the book you're about to read) was in a comic strip called "Heaven and Heller." An editor at Field Enterprises, around 1975, asked me to take a stab at creating a new story strip. That editor- Rick Marschall- was bucking the conventional wisdom, still held today, that story strips were no longer marketable.

The Heller samples (two batches were done- one by Ray Gotto, creator of the baseball strip "Ozark

Dee"; another by Fernando DaSilva, the last assistant to Alex Raymond, creator of "Flash Gordon") had to do with a seance being held in Chicago by Harry Houdini's widow: the true-crime aspect of the Heller novels was there, in embryonic form.

"Heaven and Heller" was sold to Field Enterprises. But my visionary editor lost his job. and the contract was cancelled. "Heaven and Heller" went into the drawer. A few years later. Rick Marschall recommended me to the Tribune Company as the writer of "Dick Tracy," a job I held fifteen years (starting in 1977)… By the way- thanks, Rick!

In the meantime,

Chinatown

happened, and a good but short-lived period private eye TV series called

City of Angels

(co-created by Stephen Cannell and Roy Huggins) appeared, as did those aforementioned novels by Bergman and Kaminsky. The private eye in period setting was becoming a distinct if underutilized sub-genre of mystery fiction.

But it still seemed to me that nobody had fully plumbed the potential of the P.I. in period. In fact, that was the problem: they were doing the private eye in period, but not in history'. It occurred to me that Heller shouldn't just bump into real people, but that he should be involved in real events… that he should crack a real unsolved case. I was not thinking in terms of a series of novels, just one book, though I did contemplate the possibility of sequels (one of the reasons I made Heller a younger man in

True Detective

than most protagonists of private eye novels).

From the first inklings of Heller, I began gathering research materials, and the case that attracted me most- that seemed like a classic under-explored Chicago subject- was the attempted assassination of FDR that wound up taking the life of Mayor Anton Cermak. My fascination for that case had been sparked by a TV show I saw as a kid…

One of the pop-culture touchstones that served to interest me in true crime and real detectives (or. should I say. real crime and true detectives) was the Robert Stack-starring television series.

The Untouchables

, based on a slightly fictionalized memoir by Eliot Ness (who was one of the real federal agents Chester Gould patterned his Dick Tracy upon).

The Untouchables

had done a two-part episode about the attempt on Chicago Mayor Cermak's life, and it was typically inaccurate- the series, while wonderful, played fast and loose with the facts even as it pretended, courtesy of real newspaperman Walter WincheH's voiceover, to be a docu-drama. Only the original two-part TV movie, "The Scarface Gang" (which aired on

Desilu Playhouse

and was a kind of accidental pilot film), hewed at all close to the facts of any of the cases the show explored.

Years later, digging into the research, I discovered a much better story in real life, having to do with Cermak's own attempt on the life of Frank Nitti. To say more would be to spoil the story you're about to read: but I will say that the facts of the Cermak case- and the mainstream historical accounts aren't much more accurate than the Robert Stack series- opened my eyes about the realities of Chicago crime and politics.

* * *

This book could not have been written without the research assistance of George Hagenauer. I don't use the word "assistant," anymore, because that doesn't do George justice- he has been my great friend and collaborator on these novels, not only helping with the research, but with the interpretation of that research. The plots have always been formed out of endless phone conversations in which George and I turn over all the facts like stones, looking for the wriggling, squirmy things underneath.

George now lives near Madison. Wisconsin, but he was born and raised in Chicago, and lived there throughout the writing of the first eight or nine Heller books. He- and another valued friend and Chicago historian, Mike Gold- helped me shape the character and the world of Nate Heller. Let me give an example.

When I first approached George, whom I knew through our mutual interest in collecting original comic art (we met at a comic book convention in Chicago), he was happy to help with the Chicago end of the research. Among other things, he said he could help with the sometimes complicated geography of the city and its many neighborhoods. He asked me about the story I had in mind.

"Well," I said, "Nate Heller is a young plainclothes cop who is forced to do something corrupt. He quits the force out of moral indignation, and opens his own detective agency."

When he stopped laughing, George said, "Max, you gotta leave all that Philip Marlowe nonsense behind, if you want to write about Chicago. This is the Depression we're talking about- a young guy would try to get on the Chicago cops for the graft. To take advantage of the corruption. And you couldn't get on the force at all without a Chinaman to pull the strings."

A Chinaman, he explained, was not an Asian gentleman, but someone rich enough, or anyway connected enough, to get a person a prized slot on the Chicago police force.

Later. George (and I think Mike Gold accompanied us on most of the trips) would walk me around the Loop, pointing out key buildings and the sites of various murders and other crimes. One time, we stopped for a Coke at a bar on Van Buren and George discreetly pointed out a transaction taking place: the bartender was paying off the beat cop.

"That's Chicago. Max," George said.

A very well-respected mystery writer wrote a negative review of one of the early Heller novels, criticizing my detective because he broke Philip Marlowe's "code." He could hardly have known that I set out with malice aforethought in

True Detective

to break every one of the rules that Chandler set for private eyes, in his famous "down these mean streets" speech. Heller takes bribes, he despoils virgins, he does any number of un-Marlowe-like things.

And yet I think he remains a hero, the best man in his shabby world- that much of Chandler I wanted to retain. The other thing was the easy-flowing poetry of Chandler's great first-person voice. (What came from Hammett was a certain way of looking at the world, and from Spillane came the level of violence and action, and Heller's thirst for getting even.)

Ironically, the use of Chandler-esque first-person in this novel was one of the most controversial aspects of

True Detective

, prior to its sale, anyway. Conventional publishing wisdom was, you didn't write a first-person novel as long as this one- readers didn't like being trapped inside one voice that long. Also, a mystery novel was supposed to be 50,000 or 60,000 words long- not over 100,000 words, like this one.

My agent at the time, a very prestigious one. didn't think

True Detective

should be about a private eye, and he thought the novel should be told in the third person, from multiple points of view. One of my favorite writers, a valued mentor of mine (very famous), agreed with my agent and told me either to re-work the novel as a non-P.I, third-person book, or just put it in a drawer.